Why a Georgia hospital closes – and a red state rethinks Medicaid

Loading...

| MILLEN, Ga.

Not long ago, news that Jenkins County Medical Center would close in this former cotton crossroads suggested a tough truth: that people and jobs were disappearing, leaving many poor and uninsured people in another struggling Southern town.

The Great Recession of 2007-2009 had already eliminated all 1,700 manufacturing jobs in this Georgia county of just 8,000 people. In the years since that recession, nearly 150 hospitals have closed in rural towns across the United States, most in the South.

But when this medical center’s closing was announced in 2017, Millen’s residents and political leaders didn’t bow to circumstance.

Why We Wrote This

Rising costs and faltering hospitals are causing many Southern conservatives to reconsider the government’s role in health care – and how affordable access bolsters community well-being.

“We had no choice but to crawl our way out of it,” says King Rocker, the town’s Republican mayor.

Economic troubles have impelled many Southern conservatives, like Mayor Rocker, to consider fresh approaches to the role that government plays in health care. Many of them, ever so slowly, have begun opening toward the idea that providing publicly funded basic health care may be vital to the overall well-being of a community.

Or as Republican pollster Brent Buchanan puts it, they see an emerging benefit from “investing in the infrastructure of people,” at a time when many conservative voters are pressed by health insurance costs.

A Georgia hospital’s shift from private to public

In the end, Millen’s community hospital was saved partly by being taken out of private management – which often closes less-profitable clinics and hospitals – and placed in the hands of a county hospital authority. Jobs trickled back.

Such a shift is a tricky proposition for the politics of the rural South, where many people, rich and poor alike, are skeptical of government imposition on the local economy.

One sign of how attitudes are shifting, however, is that some states are reconsidering their long-standing refusal to expand Medicaid, the federal-state insurance program for low-income or disabled people.

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, known colloquially as “Obamacare,” provided new federal funds for states to expand eligibility in their Medicaid programs.

Most states – except for 10 mostly Southern ones – participate. One result is higher costs for U.S. taxpayers. But Medicaid expansion has successfully reduced uninsured rates in rural areas, improved access to care for low-income people, and lowered uncompensated care costs for hospitals and clinics.

Lawmakers here in Georgia, as well as in Mississippi and Alabama, are reconsidering their opposition amid pleas from some in the health care industry. They have also been moved by growing support from an aging electorate concerned about health care costs.

“Republican primary voters are willing to make that investment because they’re now the ones most likely to benefit from expansion within the Southern states, specifically,” says Mr. Buchanan.

Some 80% of Georgians who make between $25,000 and $50,000 a year support expansion, according to a University of Georgia poll in January. Similarly, 55% of GOP primary voters in Mississippi said in one February poll that they would support closing coverage gaps.

The numbers are compelling. Expanding Medicaid, in fact, could allow more than 600,000 low-income, uninsured people in those three states alone to gain coverage, experts and industry-watchers say.

“Republican legislators in some states are certainly becoming more open to the idea of not leaving that [federal] money on the table anymore,” says University of Georgia pollster Trey Hood. “Maybe some of it is an overture to the working class.”

Private hospitals tilt away from Medicaid

The Medicaid issue also intersects with the question of hospital closings and the growing privatization of U.S. hospitals, many of which began with nonprofit missions by churches, charity groups, or local municipalities.

Even as public reliance on Medicaid has been rising, public-turned-private hospitals now admit 15% fewer Medicaid patients than they once did, according to a 2023 Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research study. Privately run hospitals may be more efficient, but they reduce access and quality of care for the most vulnerable Americans.

Medicaid is not a panacea for the struggle of rural hospitals. But in Georgia, a potential $1.2 billion influx under expansion would cut costly indigent care.

When North Carolina, which has a Republican legislature and a Democratic governor, accepted Medicaid expansion last year, more than 300,000 people in the state signed up.

Health insurance is an amenity that can boost economic development, but many Republicans worry about the costs to taxpayers.

“Part of this is distrust,” says Charles Bullock III, a political scientist at the University of Georgia, in Athens. “The idea that, yes, [Medicaid expansion] is a great deal on the front end with the feds picking up nearly all the costs. But ... if they do pull the football away, it turns into a losing-type situation.”

And Republicans traditionally don’t want to be associated with tax-supported entitlement programs – especially ones with roots in Washington.

“[Politicians in these states] say, ‘We don’t need to expand Medicaid – we take care of our poor,’” says Nancy Nielsen, senior dean for health policy at the University at Buffalo and former director of the American Medical Association.

Create alternatives or pivot toward Medicaid?

A cautionary tale for them is Indiana. One of the first Republican-led states to expand Medicaid, the Hoosier State blamed forecasting errors and ballooning long-term care costs for a $1 billion Medicaid shortfall in 2023.

Georgia has been trying alternatives. A homegrown program has enrolled just a few thousand people, with an 80-hour-a-month work or volunteer requirement to weed out fraud.

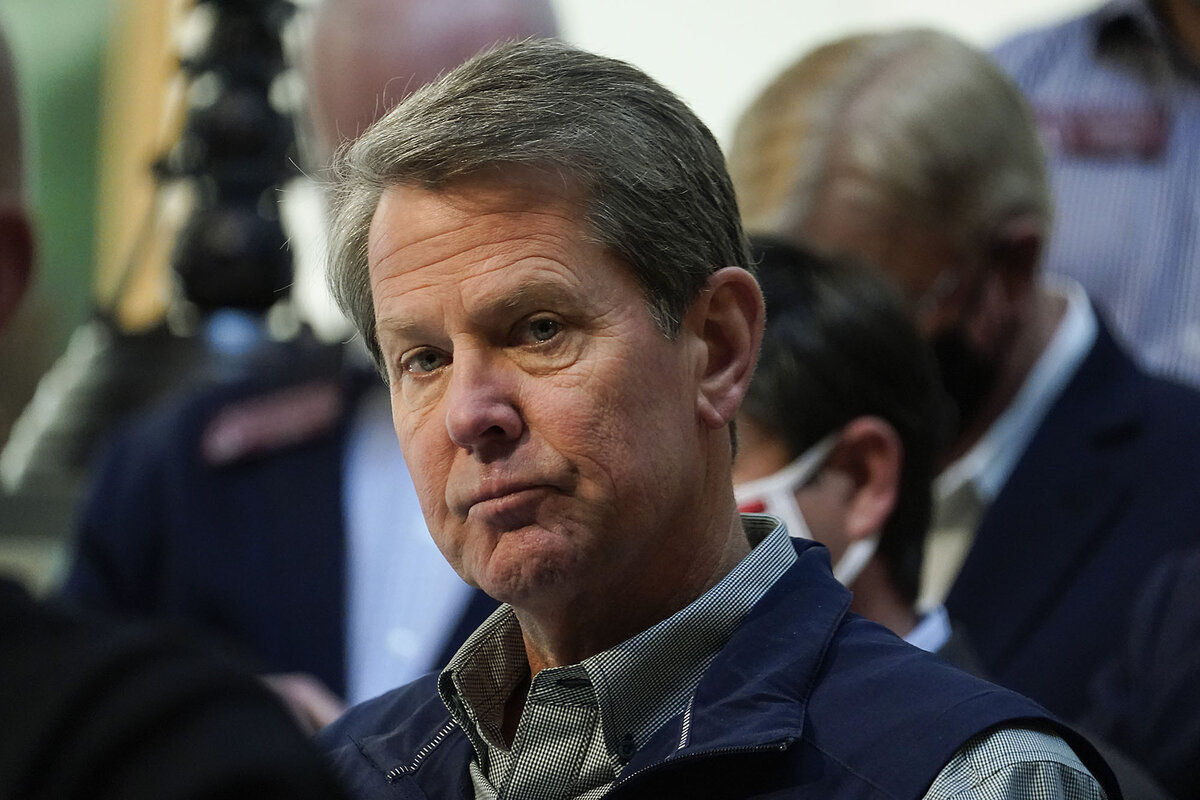

On April 19, Gov. Brian Kemp signed a bill that cut regulations on local hospitals to stem the closings. He stopped short of endorsing Medicaid expansion. But the new law creates a commission to examine issues facing uninsured Georgians.

Georgia Sen. Matt Brass, a Republican, switched to “yes” in a recent committee vote on Medicaid expansion. He worries about employees at his business who need more health care access. “Sometimes, roofs leak,” he said during testimony, referring to how unexpected costs can undermine family budgets. The measure failed by a 7-7 committee vote.

Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves has opposed Medicaid expansion. But the state’s new House speaker, Republican Jason White, has prioritized it.

“Republican strategists are looking at this and saying, ‘Why do we have to play defense on the health care issue when it is so popular?’” says Professor Bullock.

In bolstering hospitals, Medicaid expansion could also boost local health care jobs.

“It’s like a negotiation of values and economic interests,’’ says Luke Shaefer, a public policy expert at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor. “Where can we land?”