After Katrina, how charter schools helped recast New Orleans education

Loading...

Before hurricane Katrina, the school system in New Orleans was like a dysfunctional marching band: It had structure and central direction, but academic failure and corruption dragged it down.

Five years later, the schools are like a nascent jazz band: bursting with energy and improvisation and making bold academic strides – but still far from achieving their full promise.

“Few cities have achieved the widespread gains in student learning that New Orleans has recorded since Katrina ... [but] state and city leaders need to keep upping their game,” says Bryan Hassel, co-director of Public Impact, an education consulting group in Chapel Hill, N.C. “Dramatic reform will always involve trade-offs, in this case a trade of stability for dynamism.”

IN PICTURES: Hurricane Katrina five years later

New Orleans has become a laboratory for education reform, largely by necessity. With virtually all its students and teachers evacuated for the better part of the 2005-06 school year, it had to dramatically downsize and regroup. In the wake of the storm, the state became the overseer of most schools through its Recovery School District (RSD), originally set up to take over academically failing schools.

That paved the way for New Orleans to be named the most “reform friendly” for education out of 30 cities analyzed recently by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

This distinction is partly because of the dominance of charter schools, which are free to experiment and which the RSD has encouraged. Out of 88 public schools in New Orleans, 61 are charters run by a variety of state and local operators. That represents 70 percent of the city’s 40,000 students (there were 65,000 before Katrina). The percentage is much higher than in any other school system in the United States.

In addition to the charters, a small number of schools are run by the local school board, and the rest are run by the RSD.

Among the changes in New Orleans schools: One structure that gave way was the collective bargaining agreement with the teachers union, which reformers have praised for giving schools more flexibility on salaries and work hours. Many new teachers have flocked to the city through alternative training programs such as Teach for America.

Demographically, the student population hasn’t changed much. Ninety percent of public-school students are African-American, and 82 percent are low-income. Both figures are within five percentage points of pre-storm figures. But it’s not clear how many are returnees versus new to the city.

Before Katrina, 64 percent of New Orleans schools were deemed academically unacceptable by the state. By 2009, that was down to 42 percent.

Another good sign: In the RSD, the number of seniors who made it to graduation rose from 50 percent in 2007 to about 90 percent in 2010.

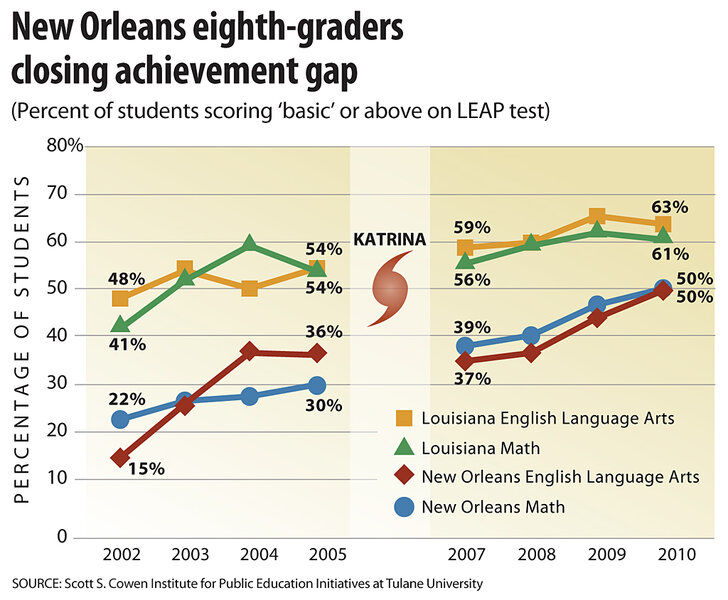

New Orleans students still test well below the state average in math and reading. They were improving before Katrina, but since schools have reopened, they’ve made gains at a much faster rate than the state.

On the 10th-grade Graduate Exit Exam, the portion of local students scoring at or above the basic level in English language arts rose from 37 percent in 2007 to 52 percent in 2010. Statewide, that number rose from 56 percent to 65 percent.

With so many changes, it’s difficult to pinpoint the cause of such gains, but several factors appear to be playing a role, says Shannon Jones, executive director of the Cowen Institute for Public Education Initiatives at Tulane University in New Orleans, which published a recent report on the schools.

For one, “schools are being held accountable for results” in a new way, she says, because parents now can choose any school in the district.

Money is another factor. An influx of federal funds, as well as private donations, has enabled schools to offer extended days or school years, invest in technology, and boost teacher salaries.

“Some of the biggest gains have been in our charter schools,” says Siona LaFrance, spokeswoman for the RSD.

The Miller-McCoy Academy for Mathematics and Business is a charter school that opened in 2008 as the only public all-boys school in Louisiana. About half the students had been failing or caught up in the juvenile justice system prior to enrolling, and “they’ve made a tremendous turnaround,” says co-founder Tiffany Hardrick.

Harriet Simms’s son Isaiah was shopping for a high school when Miller-McCoy started up. She’s pleased with the business and college-prep focus of the school. “He’s really growing,” she says.

Isaiah is due to graduate in 2012, just before the school is slated to move out of trailers into a new building that’s part of the first phase of the master plan for the renovation and rebuilding of New Orleans schools.

The city’s school officials were excited this week to receive news that they’ll receive $1.8 billion from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which should fully fund the master plan, Ms. LaFrance says.

Ms. Simms’s one complaint is that it’s hard to find good schools for her children in her neighborhood, Gentilly, which was hit hard by the storm. The local elementary school sat an abandoned wreck for more than a year after Katrina before the city demolished it.

For all the improvements, “parents don’t feel like they have a lot of choice ... [because] there’s not a plethora of excellent schools,” says Aesha Rasheed, executive director of the New Orleans Parent Organizing Network. “The challenge for us [now] is to complete the promise that was made to our community that we would actually get on the path of having excellent schools for every child. We can’t stall out at some better schools for some children.”