Student debt: What's been driving college costs so high, anyway?

Aaron Marks graduates this spring with a business degree from a good college, Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and, unlike many of his classmates, a good job.

He also has $191,000 in student loan debt.

Mr. Marks's debt is extraordinarily high, but stories like his abound. Two-thirds of students graduate with debt, to the tune of $25,000, on average.

Keeping interest rates low on federally subsidized student loans – a challenge that has lately occupied Washington – would make only a dent in what student borrowers owe. Hence, the conversation is beginning to shift to the other side of the equation: the rising cost of college.

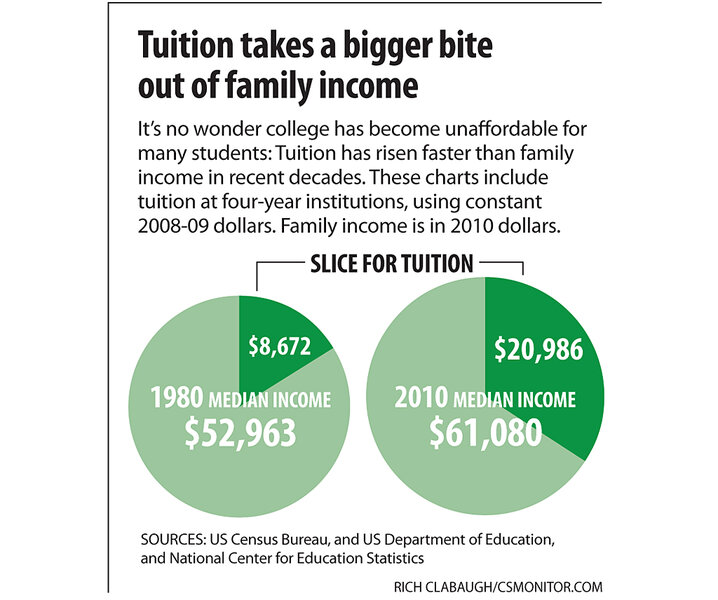

Between 1999 and 2009, tuition at public four-year colleges rose 73 percent on average, and tuition at private nonprofit colleges jumped 34 percent. In the same period, median family income fell by about 7 percent.

"One of the reasons we have a hard time wrapping our arms around [the college affordability issue] is that there's not one villain or one hero," says Patrick Callan, president of the Higher Education Policy Institute, a nonpartisan organization focused on higher ed issues. "It's kind of the perfect storm."

Among the contributing factors: state budget cuts, which prompted many public colleges to raise tuition and fees; a gradual shift of responsibility for payment from government to students and their families; and a "seller's market" in which colleges can raise tuition without repercussions.

Until relatively recently, a college degree was fairly affordable, especially if a student was willing to work and to attend an in-state public school. That started to change in the 1980s. But in the past decade, the cost of a college education has skyrocketed, rising faster than inflation – faster even than health-care costs.

Take the University of Washington. Twenty-five years ago, a student who worked half time during the school year and full time in summer could pay for college, says Mr. Callan, whose institute recently studied tuition rates there. "That's not true anymore," he adds. "You couldn't even come close."

Student and family response: borrow more

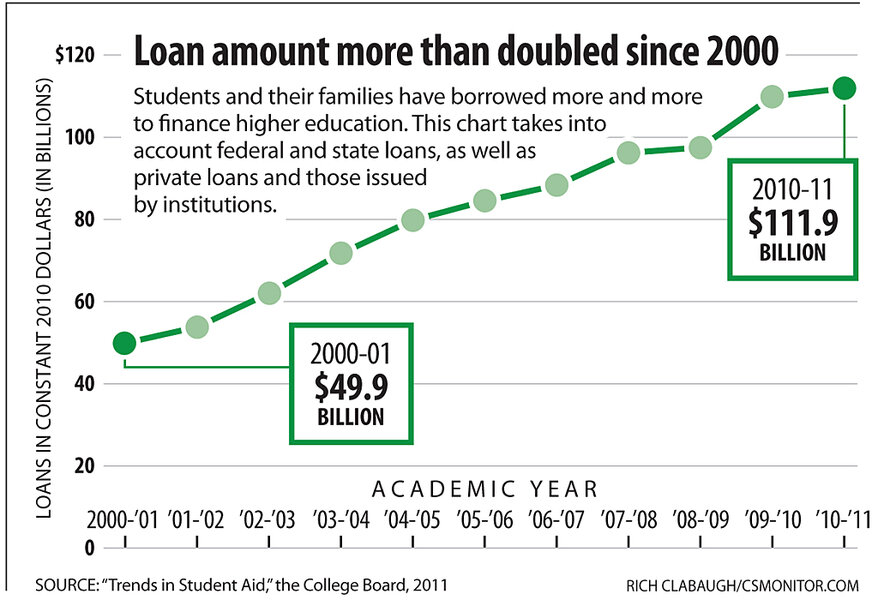

As a result, more students everywhere are taking out loans. Last year, cumulative student loan debt surpassed $1 trillion for the first time – more than is owed on credit cards or car loans.

In Washington, Congress has been struggling with legislation to keep rates on some low-interest student loans from doubling as of July 1, though both parties say they want to do so. President Obama, meanwhile, has touted the need for college affordability, holding a summit with some university presidents in December and pointing to the problem during his State of the Union message. Vice President Joe Biden met with more top university officials this month. The White House has urged greater transparency about the cost of schools and how much their typical graduates go on to earn, and has proposed withholding some federal funds from colleges that raise tuition too much.

"Higher education shouldn't be a luxury," Mr. Obama said in his January address. "It is an economic imperative that every family in America should be able to afford."

But so far, students remain willing to pay, concluding that to forgo a college degree would be worse for them in the long term. And many colleges, especially the best ones, are still flooded with applications.

Little incentive to contain costs

"There's a lack of incentive in higher education to be cost-efficient," says Richer Vedder, director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, a think tank on higher education finance. Constituencies that usually matter most to college administrators are faculty, alumni, and, to a lesser extent, students, he notes. Parents, who are often footing the bill, don't factor in much, and even many students with loans are not yet thinking about the cost.

Alumni want new stadiums and good football teams; faculty want good salaries and a low teaching load; students want nice dorms and facilities – all things that cost money.

Even the college rankings in U.S. News & World Report can help drive up costs. Colleges can move up in the rankings by paying professors more, having more alumni who contribute to the school, and attracting better students.

"How do you get good students?" asks Mr. Vedder. "You bribe them [with things like merit scholarships and fancy facilities]. There is a sort of academic arms race. To get to the top, you have to spend. You're not only raising money to keep people happy on campus, but also to improve reputation."

Marks, for one, knew he was taking on loads of debt when he opted to attend Carnegie Mellon, where tuition is almost $45,000 a year. But he thought the degree would be worth it. Now he's in a 30-year repayment program in which his monthly payment is $1,300 – and will only grow over time. "I kind of knew what was going on," Marks says about his borrowing decision. "But you don't really think about what it actually means to have a house worth of debt, on a higher interest rate than a mortgage, until you're getting close to graduating and thinking about having to repay [it]."

The recent recession has contributed to soaring college costs, too. Public schools, in particular, have been hit by budget cuts from state legislatures – and they are making up for much of it by raising tuition. In many instances, public colleges now get more money from tui-tion dollars than from the state – a reversal of the traditional setup.

"States tend to be, with a couple of exceptions, very good to higher education during good times and very hard on higher education during bad times," says Terry Hartle, a senior vice president at the American Council on Education (ACE). Compared with the three other major state expenditures – K-12 education, Medicaid, and prison systems – "higher education has a lot of people who look like paying customers," says Mr. Hartle, "and the decision is usually that we will ask them to pay more."

Access to loans begets higher tuition?

Some people see another culprit in the rising cost of higher ed: wide availability of federal loans. Often called the Bennett hypothesis, for former Education Secretary William Bennett, the argument – which remains controversial – is that federal financial aid allows schools to raise tuition because it shifts costs from schools to the government and the families who are borrowing.

"You can't say the loans caused this," says Callan, but he says he believes the generous loan programs contributed to the rapid tui-tion hikes of the past 25 years. "It doesn't mean we should make them go away, just that we should recognize them as a piece of the puzzle."

Finally, traditional universities are notoriously inefficient, with high fixed costs: lots of buildings, big campuses, and large faculties and staffs.

Moreover, containing costs isn't always a priority. Most schools aren't in session year round, and most retain the traditional model of a college class, with a professor teaching a roomful of students.

Still, that structure is changing, and it is expected to change more as pressure rises for a high-quality, lower-cost education. While some middle-class Americans may put a value on the "college experience" of a campus and dorm life, the majority of today's students – often older, working part time, or living at home – just want a good degree for less money.

"The key watchword in higher education is disruptive innovation," says ACE's Hartle. "We're living in a period where the availability and delivery of information are changing very rapidly."

Technology to the rescue?

Already, Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are collaborating to offer online courses free of charge, beginning this fall. The schools, which will use an open-source software platform for the courses, say they hope other schools will use it to offer courses, too. Stanford University's School of Engineering is also offering free online courses. Those courses, which transfer knowledge but don't lead to a degree, may not be the answer to high college costs, but they hint at new ways schools can deliver good teaching for less money.

At the University of Maryland, where cost-cutting is a priority, "course redesign" is under way throughout the 11-campus system. Working with the Center for Academic Transformation, the state's public colleges have changed the designs of lower-level "bottleneck" courses: ones with high failure and attrition rates and large class sizes, often in math and sciences.

The new online-only format for those courses not only has cut costs by about 25 percent, but also has led to greater success rates for students, says Chancellor William "Brit" Kirwan. "Rather than large lecture classes, which are a very passive learning environment, we turned them into active learning classrooms," he says. Systemwide, about 60 courses are now offered this way, serving about 12,000 students.

Dr. Kirwan and the board of regents have also consolidated administration; purchased goods as a system, rather than through individual institutions or departments; and moved to a single energy contract and a single software contract with Microsoft. They required faculty to spend 10 percent more time with students and limited the number of credits a major could require students to earn. The result: They cut $250 million from the base budget operation.

More important, Kirwan says, is that the university system earned credibility with state government – and helped to persuade law-makers to avoid draconian cuts during the recent recession.

Kirwan says cost-cutting must become a priority for more higher ed institutions – and he sees technology, like the systems he has used to redesign courses, as a big part of the solution.

"This is an absolutely critical moment for our nation," he says. "We are at risk of losing our competitive edge.... Every other enterprise I know of in America, except maybe symphony orchestras, has been able to find ways to use technology to lower their cost structure."

Callan agrees, but adds that the student-loan crisis should be a call to rethink the higher-ed finance system in a more fundamental way.

"In this country, every generation has paid for the bulk of the education costs of the generation that came behind it, through taxes or parental support," he says. "Now we're saying, 'you're on your own, pay for it out of future earnings,' even though there's not a lot of confidence that those earnings will be as good as in previous years.... Is this really the way we should fund education in this country?"