Accused on campus: John Does push for right to cross-examine

Loading...

When two students have opposing accounts in a sexual misconduct investigation on campus, should they be able to cross-examine each other?

It’s a question coming up increasingly as accused students – some 500 of them since 2011 – take universities to court, claiming Title IX disciplinary processes are unfair to them.

Why We Wrote This

What’s the fairest way to get at the truth in a sexual misconduct investigation? Courts, college officials, and student advocates are considering how to ensure that disciplinary hearings do more good than harm.

The push for cross-examination comes from some people’s conviction that it is the best way to get at the truth. But to others it raises concerns about witness badgering and causing a chilling effect on the reporting of sexual violence.

The goal of due process advocates is not for the “pendulum to swing back” to when it was widely perceived that schools were “sweeping cases of sexual misconduct under the rug,” says Samantha Harris, a vice president at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. “It isn’t a zero-sum game where either the victims are not getting a fair shake or the accused are not getting a fair shake. It should be a fair process that is maximally aimed at getting at the truth of what actually happened.”

“Risky Business.” That was the theme of the fraternity party where two University of Michigan juniors danced together and eventually made their way to his bedroom. Their accounts of what happened after that diverge sharply.

She filed a campus complaint, saying she had been too drunk to consent to sex. He told a campus investigator she didn’t appear drunk, and she verbally consented. After he was found responsible in a case where the evidence was split virtually 50-50, he withdrew from school just 13.5 credits shy of graduation.

But in this case – and about 500 other federal and state lawsuits since 2011 – the accused took the university to court, claiming the school’s Title IX disciplinary process was unfair. Echoing a concern raised in many of these suits, the University of Michigan student said he should have been allowed to cross-examine his accuser and her witnesses, to bring out possible inconsistencies, mistaken memories, or ulterior motives in a way a written report never could.

Why We Wrote This

What’s the fairest way to get at the truth in a sexual misconduct investigation? Courts, college officials, and student advocates are considering how to ensure that disciplinary hearings do more good than harm.

As the push for cross-examination accelerates, questions around the practice are far from settled: Is it the best way to get at the truth in some campus sexual misconduct cases? Or is it a threat to progress? Can there be a version that looks very different from the courtroom stereotype of badgering the witness?

The issue poses “very difficult tradeoffs,” says R. Shep Melnick, a politics professor at Boston College. “There are the dug-in advocates on either side … [but] I do think that in most universities, faculty and students are amenable to a middle ground.”

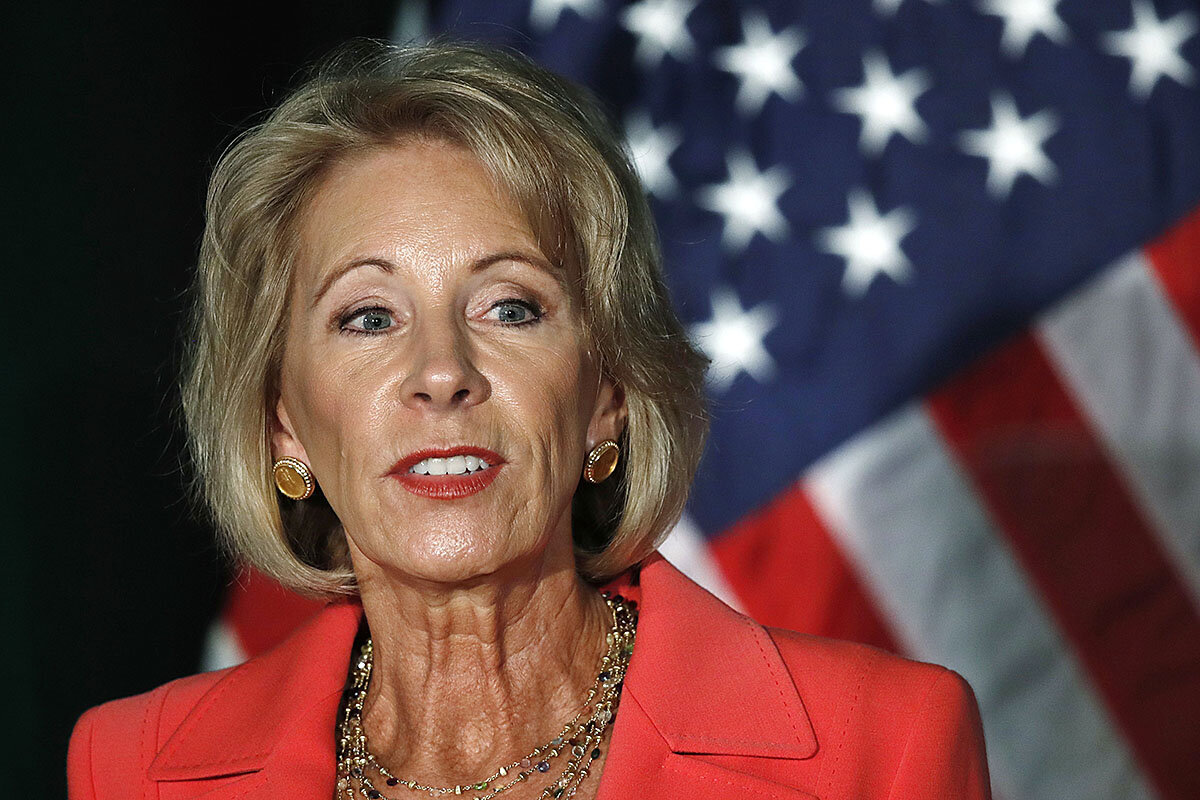

Adding to the momentum is a nod by the federal government. U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos proposed new Title IX regulations last November, including a requirement that campuses allow cross-examination by students’ advisers. It was one of several shifts toward due process that she argued had suffered under the Obama administration’s Title IX enforcement.

After a contentious public comment period and any revisions that may have been made in response, the new regulations are on track to be released this fall, an Education Department spokesman said in an email to the Monitor. Questions have been raised about whether the regulations will take into account recent court decisions on cross-examination, but the department wouldn’t comment.

Inconsistent practice

Those who have spent decades trying to encourage more people to report campus sexual violence say the drive toward cross-examination is alarming. Rape has long been underreported to police because of how victims have been treated in courtrooms, they point out.

And the Title IX approach is supposed to be different, they add: Not a criminal trial, but a way for educators to ensure that students’ civil rights aren’t curtailed because of sexual harassment and assault. There are plenty of ways for campus officials to weigh people’s accounts without subjecting them to direct, adversarial questioning, these advocates say.

In the University of Michigan case, Doe v. Baum, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals took the man’s side in its 2018 ruling: If there are competing narratives, public universities must allow the parties or their representative to cross-examine in front of a neutral fact-finder. Because of the court’s jurisdiction, its decision is binding on public campuses not only in Michigan, but also in Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

But around the country, discipline practices on many campuses don’t include any form of cross-examination, and can be “very frustrating” for accused students who say their sexual interactions were consensual, says Cynthia Garrett, co-president of Families Advocating for Campus Equality, which provides support for accused students and pushes for Title IX reforms.

Often they are asked “to prepare a list of questions in advance and hand them over to a supposedly neutral adjudicator,” she says. But then adjudicators skip a lot of questions, or ask “in a way that softens the question, makes it less adversarial, which completely undermines the purpose.”

Universities “owe a duty of care to both parties,” she says.

Searching for a path to equity

Treating both sides fairly is important, but cross-examination isn’t the right way to define due process in this context, says B. Ever Hanna, policy director of End Rape on Campus (EROC), a national nonprofit advocacy group in Washington, D.C.

An accused student should be able to “have questions answered, but not necessarily in an adversarial way,” says Hanna. The lawyer or adviser who might represent the student wouldn’t necessarily “have the training required to cross-examine survivors of sexual violence with an eye toward not further harming them.”

But school administrators would have the power to rein in anyone who crossed that line, Ms. Garrett says. And people could be questioned over video if they wanted to avoid being in the same room as their alleged assailant.

A perception of being harmed by the process can cut both ways. For an accused student, “to have your school, whom you love and you’re loyal to, actually not believe that you would never do something so vile – it’s a huge emotional experience,” she says.

‘Not the right solution’

Bias favoring those who report sexual assault needs to be addressed on many campuses, but cross-examination is not the right solution, says Brett Sokolow, president of the Association of Title IX Administrators.

“I’ve seen every type of questioning process play out,” he says. Direct cross-examination has “an enormously harmful potential … and there’s absolutely no empirical evidence of a benefit.”

An August ruling by the 1st Circuit made a similar point, but didn’t dismiss the need for some form of probing questions.

In that case, James Haidak, a student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, had been suspended and later expelled after allegations of physically assaulting a fellow student he was dating.

While the court did find that the school should have given Mr. Haidak a hearing before his suspension, it disagreed with his claim that he should have been allowed to directly cross-examine the other student. The ruling described how administrators reasonably carried out an “inquisitorial” method, “a non-adversarial model of truth seeking. It was the university’s responsibility, rather than the parties’, to investigate the facts and develop the arguments.”

But when universities take on this responsibility, they must be willing to ask probing questions of the accusing student, the ruling cautioned. Administrators in this case did that so effectively, it noted, that even without Mr. Haidak’s involvement, they surfaced information that prompted them to drop some of the misconduct charges.

In addition to Massachusetts, the ruling covers public universities in Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Puerto Rico.

The 6th Circuit Baum ruling is stronger, but the Haidak case was on balance a victory for due process, says Samantha Harris, vice president for procedural advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE). The Philadelphia-based advocacy group filed a friend of the court brief in favor of Mr. Haidak.

Most of the lawsuits have been brought against public universities, but rulings in two recent cases have raised the idea that cross-examination could be required for fairness under Title IX at private colleges as well, KC Johnson, a Brooklyn College professor who tracks such cases, wrote in an email to the Monitor.

As more cases work their way through circuit courts in the coming years, conflicting opinions could set the stage for a Supreme Court ruling.

John Does are attempting to push the envelope even further in lawsuits against Michigan State University and the University of California. They are seeking class-action status and asking to overturn hundreds of Title IX decisions against students who did not have an opportunity to cross-examine. Those “strike me as a long shot,” Professor Melnick says.

The goal of due process advocates is not for the “pendulum to swing back” to when it was widely perceived that schools were “sweeping cases of sexual misconduct under the rug,” says FIRE’s Ms. Harris. “It isn’t a zero-sum game where either the victims are not getting a fair shake or the accused are not getting a fair shake. It should be a fair process that is maximally aimed at getting at the truth of what actually happened.”