How can schools dig out from a generation’s worth of lost math progress?

Loading...

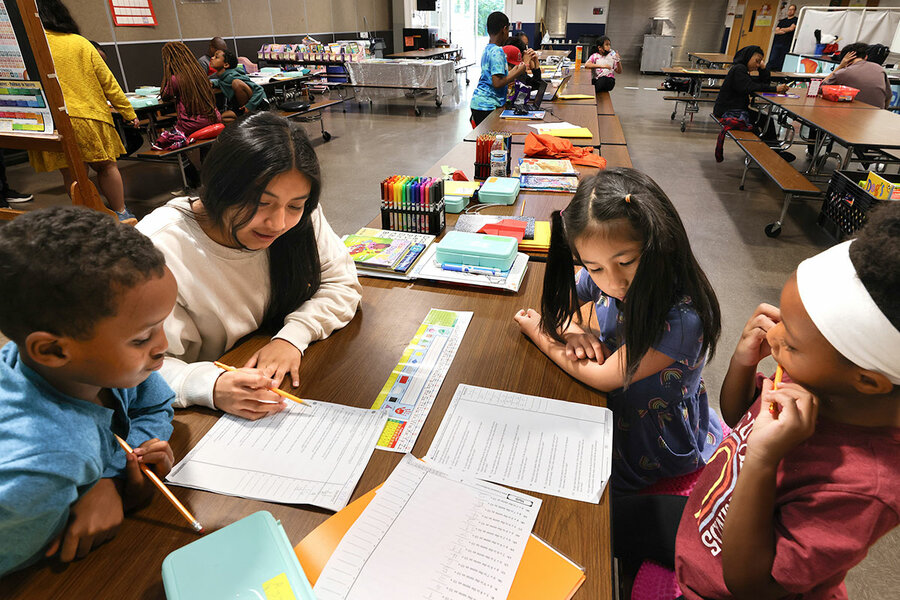

On a breezy July morning in South Seattle, a dozen elementary-aged students run math relays behind Dearborn Park International School.

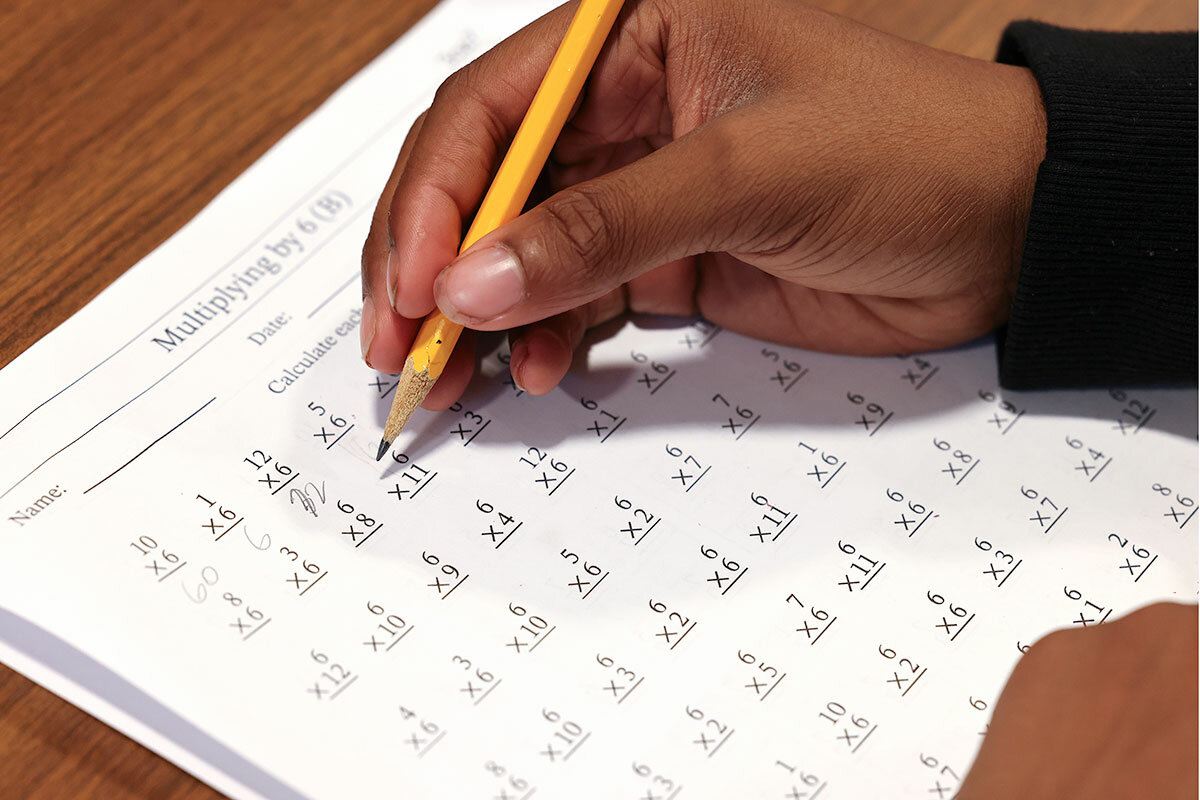

One by one, they race to a table where a tutor watches them scribble down the answers to multiplication questions before sprinting back to high-five their teammate. These students are part of a summer program run by nonprofit School Connect WA, designed to help them catch up on math and literacy skills they lost during the pandemic. There are 25 students in the program hosted at the elementary school, and all of them are one to three grades behind.

James, age 11, couldn’t do two-digit subtraction last week. Thanks to the program and his mother, who has helped him each night, he’s caught up.

Why We Wrote This

Sluggish growth in math scores for U.S. students began before the pandemic, but the problem has snowballed into an education crisis. Over the next two months, the Monitor, in collaboration with seven other newsrooms, will be documenting the challenges – as this first piece does – and highlighting examples of progress in a series called The Math Problem.

“I don’t really like math but I kind of do,” James says. “It’s challenging but I like it.”

Across the country, schools are scrambling to get students caught up in math as post-pandemic test scores reveal the depth of kids’ missing skills. On average students’ math knowledge is about half a school year behind where it should be, according to education analysts.

Children lost ground on reading tests, too, but the math declines were particularly striking. Experts say virtual learning complicated math instruction, making it tricky for teachers to guide students over a screen or spot weaknesses in their problem-solving skills. Plus, parents were more likely to read with their children at home than practice math.

The result: Students’ math skills plummeted across the board, exacerbating racial and socioeconomic inequities in math performance that existed before the pandemic. And students aren’t bouncing back as quickly as educators hoped, supercharging worries about how they will fare as they enter high school and college-level math courses that rely on strong foundational knowledge.

Students had been making incremental progress on national math tests since 1990. But over the past year, data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the “nation’s report card,” showed that fourth graders and eighth graders’ math scores slipped to the lowest levels in about 20 years.

“Another way to put it is that it’s a generation’s worth of progress lost,” says Andrew Ho, a professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

At Moultrie Middle School in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Jennifer Matthews has seen the pandemic fallout in her eighth grade classes.

Some days this past academic year, for example, only half of her students in a given class did their homework.

Ms. Matthews, who is entering her 34th year of teaching, says in the last few years, students seem indifferent to understanding her pre-Algebra and Algebra I lessons.

“They don’t allow themselves to process the material. They don’t allow themselves to think, ‘This might take a day to understand or learn,’” she says. “They’re much more instantaneous.”

And recently students have been coming to her classes with gaps in their understanding of math concepts. Working with basic fractions, for instance, continues to stump many of them, she says.

Because math builds on itself more than other subjects each year, students have struggled to catch up, says Kevin Dykema, president of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. For example, if students had a hard time mastering fractions in third grade, they will likely find it hard to learn percentages in fourth grade.

Math teachers will play a crucial role in helping students catch up, but finding those teachers in this tight labor market is a challenge for many districts.

“We’re struggling to find highly qualified people to put in the classrooms,” Mr. Dykema says.

“How are we supporting students?”

Like other districts across the country, Jefferson County Schools in Birmingham, Alabama, saw students’ math skills take a nosedive from 2019 to 2021, when students not only dealt with the pandemic and its fallout, but also a new, tougher math test. Math scores plunged 20 percentage points or more across 11 schools that serve middle school students.

It raised the inevitable question: What now?

Using federal pandemic relief money, some schools have added tutors, offered extended learning programs, made staffing changes or piloted new curriculum approaches in the name of academic recovery. But that money has a looming expiration date: The September 2024 deadline for allocating funds will arrive before many children have caught up.

Progress is possible in upper grades, says Sarah Powell, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin whose research focuses on teaching math. But she says it’s easy for students to feel frustrated and lean into the idea that they’re not a “math person.”

“As the math gets harder, more students struggle,” she says. “And so we need to provide earlier intervention for students, or we also need to think in middle school and high school, how are we supporting students?”

Jefferson County educators took that approach and, leveraging pandemic funds, placed math coaches in all of their middle schools starting in the 2021-2022 school year.

The math coaches work with teachers to help them learn new and better ways to teach students, while math specialists oversee those coaches. About 1 in 5 public schools in the United States have a math coach, according to federal data.

Jefferson County math specialist Jessica Silas – who oversees middle school math coaches – says she and her colleagues weren’t sure what to expect. But efforts appear to be paying off: State testing shows math scores have started to inch back up for most of the district’s middle schools.

Ms. Silas is confident they’re headed in the right direction in boosting middle school math achievement, which was a challenge even before the pandemic. “It exacerbated a problem that already existed,” she says.

Ebonie Lamb, a special education teacher in Pittsburgh Public Schools, says it’s “emotionally exhausting” to see the inequities between student groups and try to close those academic gaps. Her district, the second-largest in Pennsylvania, serves a student population that is 53% African American and 33% white.

But she believes those gaps can be closed through culturally relevant and differentiated teaching. Ms. Lamb says she typically asks students to do a “walk a mile in my shoes” project in which they design shoes and describe their lives. It’s a way she can learn more about them as individuals.

“We have to continue that throughout the school year – not just the first week or the second week,” she says.

Ultimately, Ms. Lamb says those personal connections help on the academic front. Last year, she and a co-teacher taught math in a small group format that allowed students to master skills at their own pace. By the time February rolled around, Ms. Lamb says she observed an increase in math self-esteem among her students who have individualized education plans. They were participating and asking questions more often.

“All students in the class cannot follow the same, scripted curriculum and be on the same problem all the time,” she says.

Memorization vs. understanding concepts

Adding to the complexity of the math catch-up challenge is debate over how the subject should be taught. Over the years, experts say, the pendulum has swung between procedural learning, such as teaching kids to memorize how to solve problems step-by-step, and conceptual understanding, in which students grasp underlying math relationships, sometimes making these discoveries on their own.

“Stereotypically, math is that class that people don’t like. And I believe part of the reason is because for so many adults, math was taught just as memorization. You had to memorize exactly what to do, and there wasn’t as much focus on understanding the material,” says Mr. Dykema, of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. “And I believe that when people start to understand what’s going on, in whatever you’re learning but especially in math, you develop a new appreciation for it.”

Ms. Powell, the University of Texas professor, says teaching math should not be an either-or situation. A shift too far in the conceptual direction, she says, risks alienating students who haven’t mastered the foundational skills.

“We actually do have to teach, and it is less sexy and it’s not as interesting,” she says.

Diane Manahan, a mother from Summit, New Jersey, says she watched the pandemic chip away at her daughter’s math confidence and abilities. Her daughter, a rising sophomore, has dyscalculia, a math learning disability characterized by difficulties understanding number concepts and logic.

For years, Ms. Manahan paid tutors to work with her daughter, a privilege she acknowledges many families could not afford. But, Ms. Manahan says, the problems in math instruction are not limited to students with learning disabilities. She often hears parents complain that their children lack basic math skills, or are unable to calculate time or money exchanges.

Ms. Manahan wants to see school districts overhaul their curriculum and approach to emphasize those foundational skills.

“If you do not have math fluency, it will affect you all the way through school,” she says.

Halfway across the country in Spring, Texas, parent Aggie Gambino has often found herself searching YouTube for math videos. Giada, one of her twin 10-year-old daughters, has dyslexia and also struggles with math, especially the word problems. Ms. Gambino says she has strong math skills, but helping her daughter has proved challenging, given instructional approaches that differ from the way she was taught.

She wishes her daughter’s school would send home information to walk parents through how students are being taught to solve problems.

“The more parents understand how they’re being taught, the better participant they can be in their child’s learning,” she says.

Stepping back, moving forward

It doesn’t take high-level calculations to realize that schools could run out of time and pandemic aid before math skills recover. With schools typically operating on nine-month calendars, some districts are adding learning hours elsewhere.

Lance Barasch recently looked out at two dozen incoming freshmen and knew he had some explaining to do. The students were part of a summer camp designed to help acclimate them to high school.

The math teacher works at the Townview School of Science and Engineering, a Dallas magnet school. It’s a nationally recognized school with selective entrance criteria, but even here, the lingering impact of COVID-19 on students’ math skills is apparent.

“There’s just been more gaps,” Mr. Barasch says.

When he tried to lead students through an exercise in factoring polynomials – something he’s used to being able to do with freshmen – he found that his current group of teenagers had misconceptions about basic math terminology.

He had to stop to teach a vocabulary lesson, leading the class through the meaning of words like “term” and “coefficient.”

“Then you can go back to what you’re really trying to teach,” he says.

Mr. Barasch wasn’t surprised that the teens were missing some skills after their chaotic middle school years. His expectations have shifted since the pandemic: He knows he has to do more direct teaching so that he can rebuild a solid math foundation for his students.

Filling those gaps won’t happen overnight. For teachers, moving on from the pandemic will require a lot of rewinding and repeating. But the hope is that by taking a step back, students can begin to move forward.

Editor’s note: This piece is the first in a series about math education from the Education Reporting Collaborative, a coalition of eight diverse newsrooms: AL.com, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News, The Hechinger Report, Idaho Education News, The Post and Courier in South Carolina, and The Seattle Times.