With Trump returning to the White House, what’s next for school choice?

The Dream Academy debuted this past fall in Iowa, opening its doors to 88 students in kindergarten through seventh grade. All are from low-income households and receive $7,826 through the state’s education savings account program.

It’s too soon to say whether the growing school choice shift toward private options has improved academic outcomes. The coming months, however, could set the tone for the movement’s future, and its effect on public schools in the United States.

Why We Wrote This

Voters rejected a trio of school choice ballot measures in November. But momentum seems anything but stalled, especially with an advocate returning to Washington.

President-elect Donald Trump is returning to the White House. He hasn’t shied away from supporting private school choice – even hinting at a federal effort to expand it. In the states, legislative sessions are ramping up. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump and his allies have embarked on a mission to lessen federal involvement in other areas of education, such as dismantling the Department of Education.

Public perception is more difficult to pin down. In November, voters in three states rejected school choice-related ballot measures. But polls show parents are in favor of flexibility. For some, state funds are a lifeline.

“We didn’t have to choose between repairing our fridge last month or continuing to be able to let our kids go to this school,” says Nebraska mother Katie Zach.

A building within walking distance of the Mississippi River may represent the future of the school choice movement.

The Dubuque Dream Center’s Dream Academy debuted this fall in Iowa, opening its doors to 88 students in kindergarten through seventh grade. All are from low-income households and receive $7,826 through the state’s education savings account program.

With funding available for private school tuition, parents quickly signed up their children for Dream Academy’s smaller class sizes and faith-based curriculum. Demand outpaced leadership’s initial plan to start with only 30 students.

Why We Wrote This

Voters rejected a trio of school choice ballot measures in November. But momentum seems anything but stalled, especially with an advocate returning to Washington.

“For them, it’s a slam dunk. It’s like, ‘Praise the Lord!’” says Robert Kimble, executive director and head of school.

It’s too soon to say whether the growing school choice shift toward private options has improved academic outcomes, especially for the nation’s most vulnerable students. The coming months, however, could set the tone for the movement’s future, as well as its effect on public schools in the United States.

State legislative sessions are ramping up, and President-elect Donald Trump is returning to the White House. He hasn’t shied away from supporting private school choice – even hinting at a federal effort to expand it. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump and his allies have embarked on a mission to lessen federal involvement in other areas of education, such as dismantling the Department of Education.

Public perception is more difficult to pin down. In November, voters in three states – Kentucky, Colorado, and Nebraska – rejected school choice-related ballot measures. But parents are increasingly signaling that they want more flexibility.

A poll released last week by the National Parents Union found that 71% of parents support using state public funding to send their children to whatever education setting they deem the best fit – a public school, private school, homeschool, or religious school. A majority of parents also think schools receiving any form of government funding should not be allowed to discriminate on the basis of age, race, gender, sexuality, and abilities.

Nearly three dozen states already have passed some form of private school choice, such as voucher programs, education savings accounts, or tax credit scholarships. And a dozen states offer a universal program, meaning families, regardless of income, can access public funds for private options. That expansion is likely to continue.

“Texas is still a bit of a wild card, but I think you’ll see continued efforts, especially in Republican-leading states,” says Douglas N. Harris, professor of economics and director of the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice at Tulane University.

Why did the ballot measures fail?

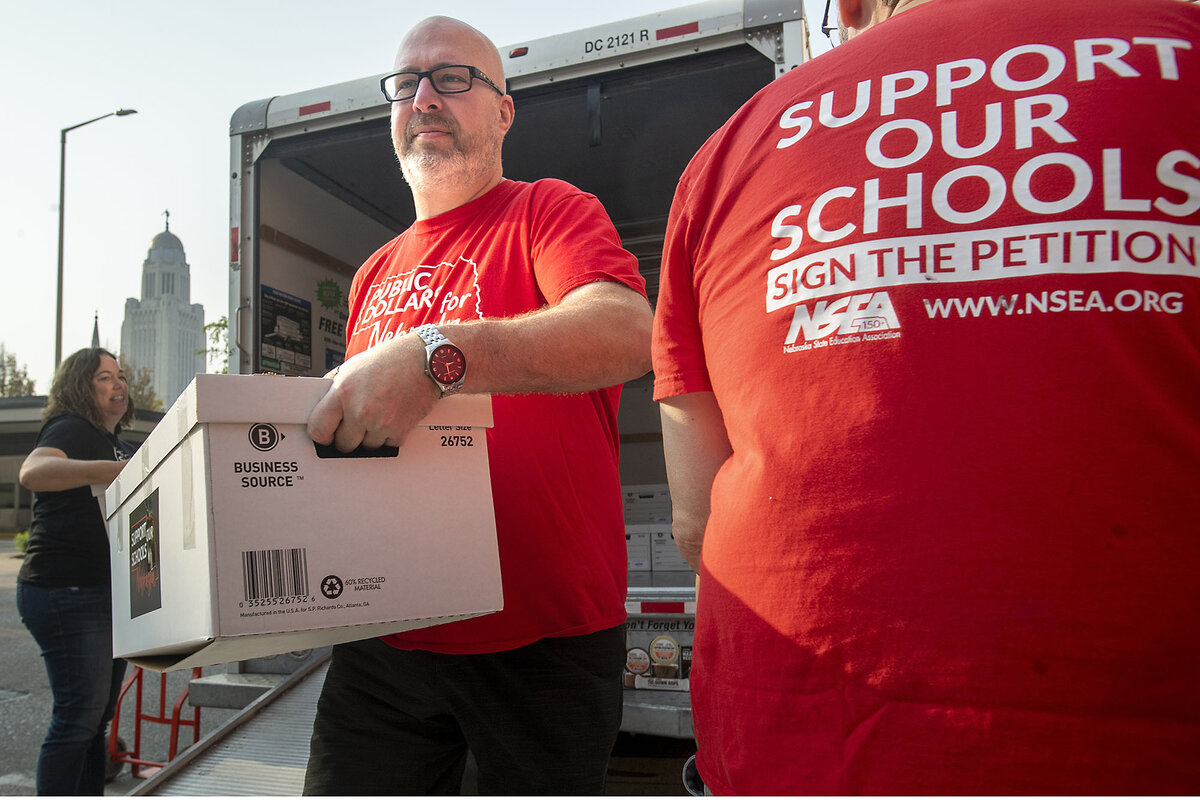

Nebraska voters repealed a program, passed by state lawmakers earlier that year, that allocated $10 million toward scholarships for students to attend a private school. In neighboring Colorado, voters rejected an amendment that would have enshrined school choice in the state constitution. And further east, Kentucky voters shot down a measure that would have allowed public tax dollars to flow toward private or charter schools.

Liz Cohen, policy director of FutureEd at Georgetown University, cautions against viewing the ballot outcomes as a bellwether for the school choice movement. Policymaking in state legislatures might just be easier to accomplish than direct votes at the ballot box.

“Most families send their kids to their neighborhood public schools, and most of them are more or less satisfied with that,” she says. “So they don’t have a lot of incentive to vote for something that they likely have been told is going to threaten the thing that they’re already satisfied with.”

In Nebraska, families that received money through the state’s private school scholarship program are on the hunt for a new source. That includes Katie and John Zach, whose four oldest children attend a Catholic elementary school in Lincoln.

Ms. Zach says the money has been a lifeline. She’s a stay-at-home mother, and her husband teaches at a Catholic high school. Given the family’s modest budget, she says the state scholarship funding made it less financially perilous to give their children a private Catholic education.

“We didn’t have to choose between repairing our fridge last month or continuing to be able to let our kids go to this school, sign up for basketball – whatever it may be,” she says.

The program’s repeal could catalyze a new approach to bring back private school choice, says Jeremy Ekeler, executive director of Opportunity Scholarships of Nebraska.

“It has been very much a policy and legislative battle,” he says. “I think we’re going to see a lot more grassroots parent advocacy.”

What to watch in the coming year

The policy battle, however, could also make its way to Washington.

During President-elect Trump’s first term in office, his education secretary, Betsy DeVos, championed the so-called Education Freedom Scholarship. The $5 billion proposal would have awarded tax credits to businesses or individuals who donated a portion of their taxable income to organizations providing scholarships. It never gained enough traction in Congress. Now Republicans have full control of the U.S. House and Senate.

Mr. Trump referenced reviving a federal attempt while announcing Linda McMahon, co-founder and former president of World Wrestling Entertainment, as his next education secretary. In a Truth Social post, he wrote that “Linda will fight tirelessly to expand ‘Choice’ to every State in America.”

If successful, the simultaneous expansion of the federal government’s role related to private schools and contraction of the Education Department would dramatically alter the tapestry of America’s public education system as it exists today.

“Those two things are in tension with each other, so it’ll be interesting to see whether they just kind of ignore that and are so determined to expand private school choice, that they do it anyway,” Dr. Harris says.

School choice supporters and opponents will be keeping a close eye on Texas, where Gov. Greg Abbott has expressed confidence about the votes needed to pass a voucher-style program this year. The reliably red state’s Legislature has resisted launching any such program, largely because of rural Republicans’ opposition. In tiny towns across the Lone Star State, the public school is the bedrock of the community.

If North Carolina is any indication, state lawmakers hold considerable power over this issue.

In September, Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed a bill that would have ramped up funding for private school vouchers, which do not have an income cap. Governor Cooper decried the expanded funding in his veto letter. He described it as a “scheme” that lacked accountability and would hurt public schools, especially in rural areas.

But the Republican-dominated state legislature overrode his veto in November, sending $463 million toward the Opportunity Scholarship program.

In Florida, the price tag has been even higher. The Education Law Center and Florida Policy Institute estimate private school vouchers are costing the Sunshine State $3.9 billion this school year. Many of those students were already enrolled in private schools.

Demand boosting supply of private schools

The proliferation of taxpayer-funded choice programs has also put a squeeze on the private education marketplace.

The Drexel Fund, a grantmaking organization, is playing a behind-the-scenes role in the movement as “demand from families outstrips the supply of private school seats,” says Mark Gleason, managing partner. It helps aspiring education entrepreneurs launch or expand private schools that primarily enroll students from underserved communities.

Since its founding in 2015, the organization has funded more than 23,000 private school seats, including those at the Dream Academy. Mr. Gleason says they are actively working in a dozen states, mostly those that have a voucher or education savings account program. The Drexel Fund expects to grow that number to 20.

Back in Iowa, the Dream Academy’s students and staff have returned from winter break. Mr. Kimble says the smaller class sizes – 10 to 15 students – are reducing behavioral problems and increasing learning time. He hopes that’s a recipe to erase long-standing racial achievement gaps and end poverty cycles.

“Let’s see what we can do,” he says. “Let’s do something different.”