Berkeley passes first-in-the-nation soda tax. Will other cities follow?

| Los Angeles

Election night 2014 saw a breakthrough of sorts in the so-called soda wars. Beginning on Jan. 1, residents of Berkeley, a California city of some 100,000, will have to pay a tax of 1 cent per ounce on calorically sweetened beverages including sodas and teas. Items such as baby formula, milk, and alcoholic drinks will not be included.

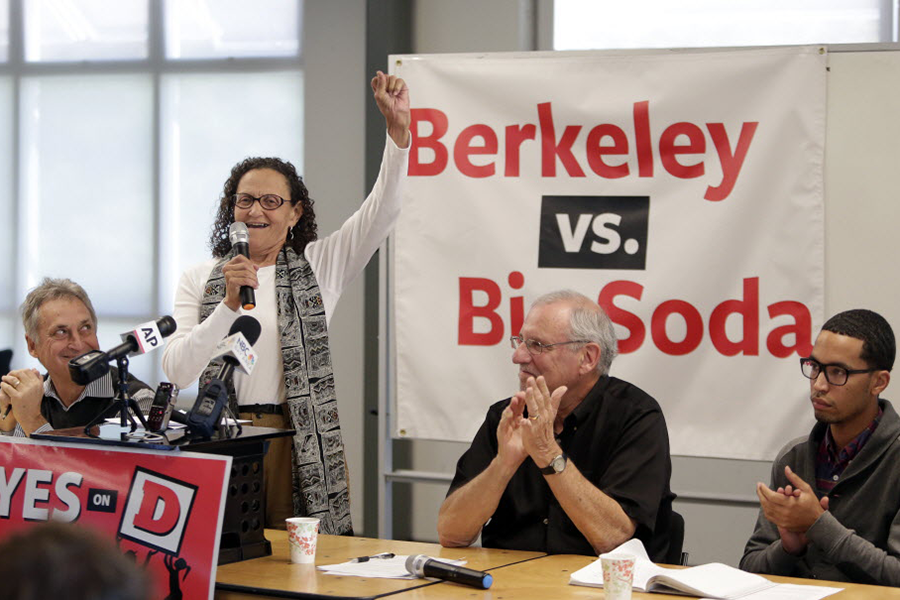

In passing the first soda tax in the United States, Berkeley has succeeded where some 30 other communities nationwide have failed. Supporters say this victory, in which nearly 75 percent of voters approved, sends a message to the rest of the country.

“We have shown that it’s possible to defeat Big Soda,” says Josh Daniels, a campaign organizer as well as freshly reelected school board member. The American Beverage Association (ABA) spent more than $2.3 million to defeat the measure, while supporters of the tax took in just over half a million dollars in cash donations, Mr. Daniels notes.

The campaign also benefited from in-kind TV ads produced by former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, who spearheaded the well-publicized but unsuccessful effort to curb the size of sodas in New York. But even with interest and engagement from around the country, it was grass-roots community involvement that was key to the campaign’s success, Daniels says.

Opponents suggest that Berkeley’s historically liberal positions, such as becoming a nuclear-free zone, do not represent the rest of the nation, and they say this position on taxing sodas will remain an outlier.

“Berkeley is unlike the rest of the country,” Christopher Gindlesperger, a spokesman for the ABA, which represents Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Dr Pepper Snapple Group, and other major beverage companies, told Politico.

“Berkeley doesn’t look like mainstream America,” he added, saying that politicians risk their future if they stake their reputations on this issue.

Longtime Berkeley resident Joan Mikkelsen says she voted against the measure. “I just don’t think that we should be disciplined by our government,” she says. What is really needed, she adds, is better education about healthy eating habits, and she doesn’t think that a tax on sweetened drinks will achieve that.

In addition, a similar measure in San Francisco, which would have imposed a 2-cent-per-ounce tax, was defeated Tuesday. It didn't obtain the necessary approval of two-thirds of voters to pass.

But from Daniels’s perspective, Tuesday night was a tipping point. The campaign, he says, has already begun taking calls from communities around the country interested in learning from Berkeley’s efforts. And Howard Wolfson, senior adviser to Mr. Bloomberg, says via e-mail that “we stand ready to assess and assist other local efforts in the coming election cycle.”

The National Consumers League in Washington also followed the campaign closely, says executive director Sally Greenberg, who notes that a similar measure was defeated in the District of Columbia in 2010. She is hopeful the city will consider the measure again, taking a cue from Berkeley. “We hope this will be the wave of the future,” she adds.

If history is any guide, other towns will indeed be encouraged to try similar measures, says Daniel Newman of MapLight, a nonpartisan nonprofit in Berkeley that tracks money in politics. Many trends, he points out, have begun in California and spread across the country, including recycling and curb modifications for wheelchair access.

In the wake of the win, Mr. Newman says, there are key lessons other communities can glean. For one thing, Berkeley residents were very aware of just how much money the ABA contributed to the opposition, he says.

“Berkeley has strong transparency regulations,” he says, pointing to full disclosure requirements for all political advertising.

This debate is not likely to go away, says Brett Wilmot, associate director of the ethics program at Villanova University outside Philadelphia. “We’ve become increasingly sensitive to the ways in which putatively private choices affect society as a whole,” he says via e-mail.

Historically, we had a bit more of a simplistic notion of how to determine whether your exercise of your liberty infringed on my exercise of my liberty, he notes. To paraphrase the British utilitarian John Stuart Mill, he says, “your right to swing your fist ends at the tip of my nose.” But individual choices to smoke, drink, and eat in ways associated with poor health outcomes don’t simply affect the individuals in question, he continues.

He writes, “we’re all linked in complex causal chains, where your decision to accept certain risks (e.g., associated with smoking tobacco) shows up as higher insurance premiums for me (or higher taxes to support things like Medicare and Medicaid).”