For presidential candidates, small events in N.H. may matter more than debate

Loading...

| Manchester, N.H.

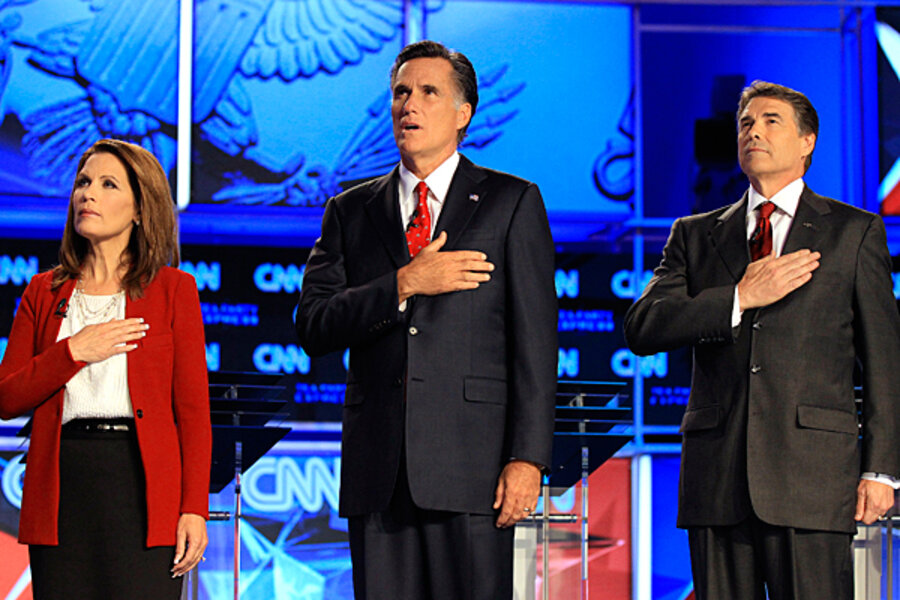

For the first time, all the leading Republican presidential candidates are converging on New Hampshire – first primary state, population 1.3 million – for a debate at Dartmouth College in Hanover on Tuesday evening.

They’re already crossing paths in picture-postcard towns honing their skills, or not, in the Granite State’s signature brand of retail politics.

What counts here isn’t the big event, but rather the face-to-face encounters in diners, living rooms, and town halls.

Other states are clamoring for the first-in-the-nation distinction, and the national attention to local issues that it brings. On Sept. 30, Florida set off a war to be an early primary state when it shifted its primary to Jan. 31. South Carolina shot back with Jan. 21, and Nevada claimed Jan. 14. Now, Iowa is eyeing Jan. 3 for its presidential caucuses.

That leaves New Hampshire in a bind. A 1975 state law requires that New Hampshire maintain its status as the first presidential primary state. New Hampshire is at least a week away from announcing the date of its primary, says William Gardner, the state’s secretary of State, but one thing is sure: No one is going to beat New Hampshire, even if it means bumping the date back to the Christmas holidays.

“If Iowa sets its caucuses on Jan. 3, that leaves some options for us, but not a lot,” said Mr. Gardner in a phone interview on Monday. “The possibility of going in December exists.”

From 1916 until 1972, the New Hampshire primary was always on the second Tuesday in March. But an electrifying 1968 New Hampshire primary forever changed that. A near unknown before he hit New Hampshire, Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D) Minnesota racked up 42 percent against a wartime president of his own party – Lyndon Johnson, whose 49 percent score registered to the public as a defeat. Mr. Johnson withdrew from the race before the next primary. In 1969, the Nevada Legislature proposed holding its primary a week ahead of New Hampshire – and it’s been a race to hold first place ever since.

In this New Hampshire primary cycle, the invitation to a “living room” meeting with a candidate is as likely to be a tent in the backyard, with room at the back for press and cameras. But the principles of retail politics here remain the same: Show up, downsize your entourage, answer the questions, and welcome the follow-ups – and if you’re not the last one to leave, look as if you wish you could be.

In all, not more than a few thousand people will go to these events, ask the telling question, or personally size up a candidate toe-to-toe. But the small army of press, video cameras, and bloggers that do show up amplify these exchanges – and the state’s reputation as something special in presidential politics.

“My brother went to the [Sept. 22 GOP] Florida debate, but he was a small guppy in a large ocean,” said Pamela Lindberg, who serves on the State Board of Education, at a Oct. 1 backyard event in Manchester for Gov. Rick Perry (R) of Texas. “Here, you are a much larger fish in a very small pond.”

“You have an opportunity to literally sit down with a candidate,” she adds. “I’ve sat down with a couple of them.”

Yet New Hampshire events themselves have evolved. “House parties that used to be rather intimate, with 20 or 30 people, are now more likely to be 150 or 200 people, with more room for the press than the actual voters,” says Andrew Smith, director of the University of New Hampshire (UNH) Survey Center in Durham.

And often, these are not as unscripted as they appear. Many small-scale gatherings are by invitation only. “What they try to do with their grass-roots campaigning is largely use them as stages to create media attention, knowing you will reach more voters through media coverage of the event than the event itself,” Mr. Smith says.

“But they’re still important,” he adds, “because the local folks will ask questions completely out of the blue that give a chance to find out how candidates can think on their feet and whether their answers are consistent.”

In his New Hampshire events to date, Governor Perry has been pushed on his stands on immigration. At the Manchester backyard event on Oct. 1, he set off alarms when he told a questioner, “It may require our military in Mexico, working in concert with [Mexican authorities] to kill these drug cartels and to keep them off our borders and to destroy their networks.” Arturo Sarukhán, Mexican ambassador to the United States, told reporters on Oct. 3 that the presence of US troops on Mexican soil “is not on the table.”

Such questions are what the New Hampshire primary is all about, says Diana Lachance, a retired truck manager from Derry, N.H., who has seen Perry twice so far at events in the states, including the Oct. 1 one.

“You have to go and see them up close, because if they’re not telling you the truth, they’re going to slip up,” she says. She has attended events for all the leading GOP contenders at least twice, she adds.

But in the end, the influence of the New Hampshire primary also depends on whether candidates are willing to spend considerable amounts of time here. Setting a primary date in December may be a bridge too far.

“If candidates decide in 2016 that New Hampshire has gone off the deep end by going so early, that could be the beginning of the end of the primary,” says Smith of UNH. “It’s like jumping the shark. You can go so far ahead that you’re not relevant anymore.”