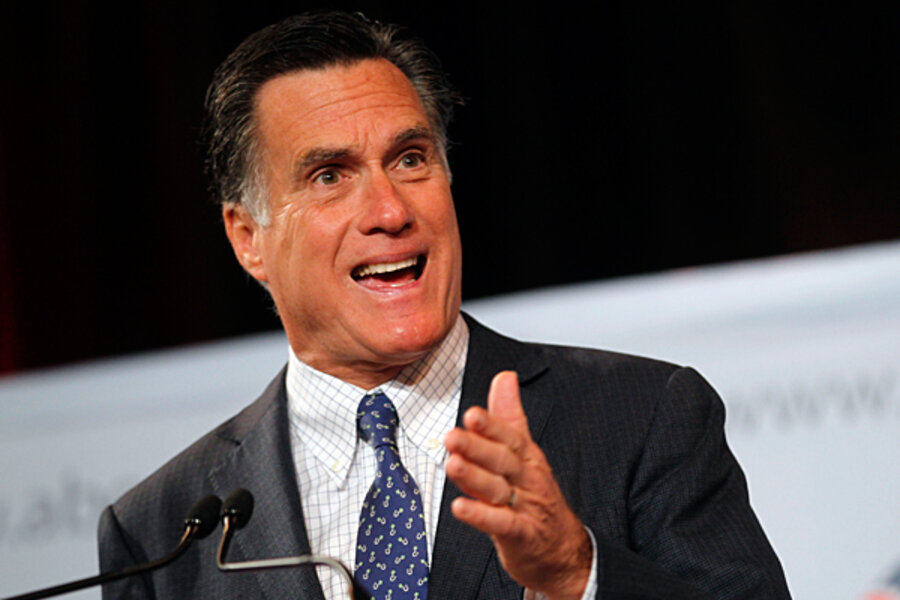

Overview. The former Massachusetts governor has a tax-cut plan that would lower rates for all income brackets, eliminate estate taxes, and reduce corporate taxes. These tax cuts would outweigh the spending cuts that he has outlined so far, according to the CRFB. Mr. Romney has stated the broad goal of capping federal spending at 20 percent of gross domestic product, considerably below its current level, so his CRFB ranking on deficit reduction could improve if he provides more detail on how he'd reduce spending.

(The CRFB says it will update its analysis as candidates provide more detail about or revise their economic plans.)

The results. National debt would rise modestly, to 75 percent of GDP by 2021. This is under a "low-debt scenario" that essentially takes the candidate's own outlook for granted. By contrast, status quo policies would push public debt to 85 percent of GDP by 2021, according to the CRFB. (For more on the status quo scenario, see the context section below.)

In an "intermediate-debt scenario," the national debt under Romney would reach 86 percent of GDP. In this kind of scenario, the CRFB takes a view that's more skeptical – or realistic, many budget analysts say – of candidate plans.

(The CRFB's study also offers an even stricter "high-debt scenario," which we'll skip here. The future deficits under all the candidates look big enough without it.)

Why his plan gets there. The improvement under the low-debt scenario hinges on Romney's proposed cap for all federal spending. Also, the CRFB's scoring of Romney occurred before he outlined a plan to reduce personal income-tax rates by one-fifth for each tax bracket (while making deductions harder to come by).

In any case, Romney's tax-cut plans cost the government some revenue. His spending policies include restraining Medicaid by block-granting the program to states and capping its growth.

The context. In the CRFB base-line scenario, Washington policies continue on essentially a status quo track: The Bush tax cuts stay in place, the alternative minimum tax is "patched" each year to avoid snaring more middle-class families, and a "doc fix" for physician payments under Medicare occurs annually.

Debt levels above 60 percent of GDP, while not necessarily devastating to the US economy, are higher than many economists would like to see. Moreover, the decade starting in 2020 will present new fiscal challenges, budget forecasters say, as baby-boomer retirement costs increasingly weigh on the federal budget.