Massachusetts Senate race shows few signs of a 2010-style upset

Loading...

| Boston

For nearly two months, the story of Scott Brown has lurked over the Massachusetts Senate race.

To the state’s Democrats, Mr. Brown, who stunned them when he won the special election for Edward Kennedy’s former Senate seat in 2010, was the antagonist of a political tale. Here’s what happens, his victory seemed to say, when the ruling party in a heavily partisan state gets too complacent.

And to the Massachusetts GOP, the folksy centrist who drove a pickup truck was everything they hoped to become: a relevant, independent voice with the potential to win major elections in one of the most reliably Democratic states in the country.

But despite his outsize symbolic presence throughout the race, Brown himself was nowhere to be seen. That is, until the eve of the election, when he appeared alongside Republican candidate Gabriel Gomez at a small rally in the Boston suburb of Quincy.

“I tell you, it’s like déjà vu, seeing the same old cast of characters doing the same old dirty tricks from the Democratic playbook,” he said to rippling applause. “You deserve better. The people of Massachusetts deserve better.”

But as the state’s voters head to the polls Tuesday to elect a replacement for Secretary of State John Kerry, few expect Mr. Gomez to pull off a repeat of Brown’s 2010 victory. In fact, this race looks a lot more like 2012, when Brown came up for reelection against Democrat Elizabeth Warren, a Harvard law professor, as well as the machinery of a state Democratic Party steeled in its resolve to undo the mistakes of two years earlier. Ms. Warren drew wide crowds and big money, and she ousted Brown easily.

Now, Democrat Edward Markey, an 18-term congressman from the Boston suburbs, has every reason to believe he will do the same. Polls have consistently placed him up by at least eight points among likely voters, and he has outraised and outspent Gomez by a wide margin.

Heaped onto those advantages is the abysmal turnout that the state expects Tuesday. Secretary of State William Galvin said he predicts no more than 1.6 million of the state’s 4.3 million registered voters to trek to the polls on this 95-degree June day – the lowest voting rate in any Senate race in modern Massachusetts history. Even that modest figure of 37 percent turnout, he told the Associated Press, may be “slightly optimistic.”

That voter lethargy has fed into opposing campaign strategies for the candidates, as both seek to make sure the right voters are among the few who turn out.

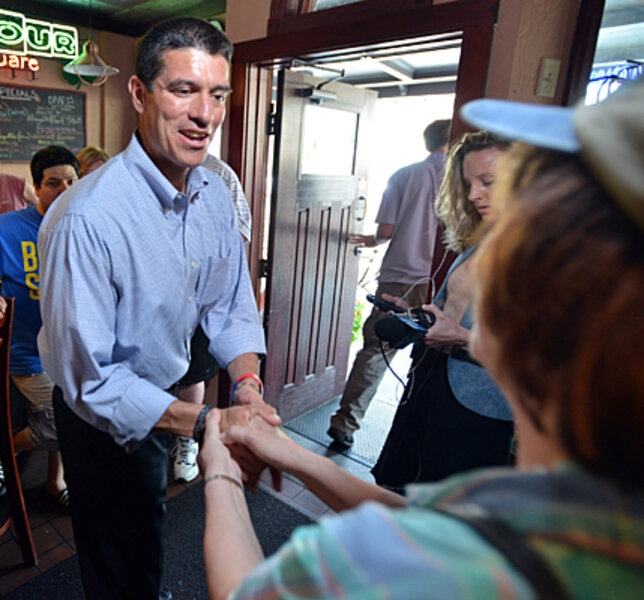

Since the primary at the end of April, Gomez, a businessman and former Navy SEAL who has never held political office, has waged a vote-by-vote battle for the hearts of the state’s independents, who make up more than half of registered voters here. He’s spent two months in a relentless parade of voter meet-and-greets, round-tables with small-business organizations, and small-town fundraising luncheons.

At every stop, he reminds voters of his personal history: He is the child of Colombian immigrants, a boy who didn’t learn English until he went to school and went on to “live the American dream.” (Less prominent in his narrative is the fact that his father was a Stanford-educated corporate executive, not a working-class immigrant pulling himself by his bootstraps.)

All the while, he has relentlessly slammed his opponent as an out-of-touch career politician, whose four decades in Congress have insulated him from the realities of American life.

"Where I come from ... in the military, you either lead or you get out of the way,” he told the crowd Monday night. “I think it’s obvious that he hasn’t led. I think it’s time for Congressman Markey to get out of the way.”

For Markey, on the other hand, the campaign strategy has been to lie low, dodging gaffes and stumbles of the kind that doomed the candidacy of Attorney General Martha Coakley, who lost to Brown in 2010.

“Brown didn’t win – Coakley lost,” said Linda Perry, a Boston lawyer and Markey supporter who turned out Saturday to hear the congressman speak alongside Vice President Joe Biden and Boston’s outgoing mayor, Thomas Menino, at an iron workers union hall in working-class South Boston.

“I like a man in uniform as much as the next girl,” she said of Gomez. “But the voters here know there’s got to be more to him than that.”

Deep in Democratic territory that day, Mr. Biden told the knot of union workers and other party faithful that they shouldn’t believe Gomez’s contention that he is a “new kind of Republican” – a social moderate who could straddle partisan lines.

“If it looks like a duck, if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck,” he said.

Behind him onstage, Markey clutched his wife’s hand and smiled widely. A slightly stiff, gangly man with a distinct Boston twang to his speech, Markey has often fallen flat in the kind of grass-roots campaigning at which Gomez excels. Yet it is Markey, not his opponent, who grew up working class and paid his own way through college and law school, although he has not made his biography a centerpiece of his run.

But behind a microphone or a debate-hall podium, he is animated and analytical, a savvy policymaker whose decades of experience are on full display. And while Gomez has struggled at times to nail down his positions, particularly on social issues like abortion, Markey is opinionated and thoughtful on a vast range of policy concerns.

Even if he wins Tuesday, however, his victory will not be a comfortable one. The winner of this election will have to run for reelection at the end of 2014, less than a year and a half from now, as part of the much longer and more energized midterm election cycle.

But Gomez’s camp isn’t counting itself out just yet. As Brown pointed out to supporters Monday night, polls in the days before his victory frequently gave an erroneous advantage to Ms. Coakley.

“It’s not over until 8:01 [p.m.],” he said.