Rice's visit to a changed Libya

| Washington

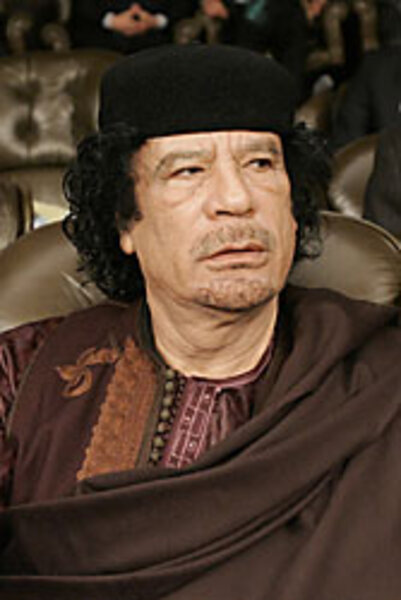

When Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice visits Libya Friday for a sit-down with the once-reviled leader Muammar Qaddafi, it will symbolize both how far US-Libya relations have come and, from the Bush administration perspective, the potential for pariah states to come in from the cold.

As Secretary Rice and Colonel Qaddafi discuss economic ties, regional issues, and oil, the United States will be hoping that Iran and North Korea, in particular, are taking note. Instead of confronting the US and the international community with a nuclear weapons program, US officials say, Libya is reaping the economic and diplomatic benefits of having renounced its terrorist avocation and weapons-of-mass-destruction ambitions in 2003.

State Department officials buttress their characterization of Rice's visit as "historic" by pointing out that the last high-ranking US official to visit Tripoli was Richard Nixon – in 1957, when he was vice president.

But not everyone sees Rice's stop in Libya in such glowing terms. Some of the families of victims of terrorist acts carried out by the Qaddafi regime are not satisfied with reparation settlements. Qaddafi himself this week appeared to play down any game-changing turn in US-Libya relations, saying he did not view the US with either "friendship or enmity."

And the demonstration effect of Libya's return to the international community following its renunciation of its nuclear and other weapons programs could also be open to debate.

"It's doubtful the Libya example will mean much to Iran, in large part because Iran is in a better position as it faces down the international community than Libya was," says James Phillips, senior research fellow for Middle Eastern affairs at the Heritage Foundation in Washington.

Oil-producer Iran is in a stronger position economically than Libya was because of today's high energy prices, Mr. Phillips says. The economic impact of international sanctions was higher for Libya because the US and Europe were more united in imposing them than is the case with Iran, he adds. "Then there's the fact that Iran is in a better position [than Libya was] in the United Nations Security Council because of the positions of China and Russia, and it adds up to a very different scenario," he says.

US officials acknowledge that Iran has shown little interest in following the Libya example in its dispute with the international community. But they say that does not negate the importance of highlighting – through Rice's trip – the turn of events involving Libya.

"Whether some of these other regimes will wake up and smell the hummus and see they are goofing up as far as their relations with the international community are concerned, that remains to be seen," says David Welch, assistant secretary of State for Near East affairs. "So far, the record of Iran's decisions is not inspiring."

But he adds that Rice is especially keen on demonstrating that even sworn enemies who have inflicted pain on Americans can reap dividends by conclusively changing their ways. "We think it's important to show that if you do the right thing, even if late, the situation can be corrected to your advantage," Mr. Welch says.

One issue still outstanding has been finalization of a claims settlement agreement that will include final payouts to the families of victims of damages caused by both countries (the US bombed Libya in 1986). The agreement will close the door on any future claims against Libya for past actions, something the families of some victims do not support.

Rice had hoped the agreement, which includes a substantial pot of money for final reparations, would be fully funded by the Libyans by the time of her trip. State Department officials say they are assured by Libyan officials that the money will be deposited soon.

The apparent delay has led to some criticism of Rice for keeping to her schedule to visit Libya, but others still see dividends. "We think the secretary's visit can advance this [issue], too," says Welch of the State Department.

The claims-settlement issue is just one complication that suggests how difficult and extended the repairing of relations with a former enemy can be. Some analysts of Libya's turnaround say the decades that have lapsed since Libya first showed signs of renouncing its involvement in terrorism suggest that time may not be on the US side in its conflict with Iran – especially with Western intelligence agencies estimating that Iran could develop a nuclear bomb within the term of the next US president.

But it may yet be possible to make a serious offer to Iran that could lead to a Qaddafi-like transition, says Randall Newnham, an associate professor of international affairs at Pennsylvania State University in Reading, who has studied the Libya case.

"Libya for years thought the biggest threat it faced was from the West, but then Anwar Sadat was assassinated [in Egypt], and suddenly it realized that maybe its biggest threat came from Islamic extremists," Mr. Newnham says. "From that point on, it made sense for Qaddafi to cooperate with the rest of the world against Al Qaeda." Iran has its own trouble with the Al Qaeda brand of Islamic extremism, he notes.