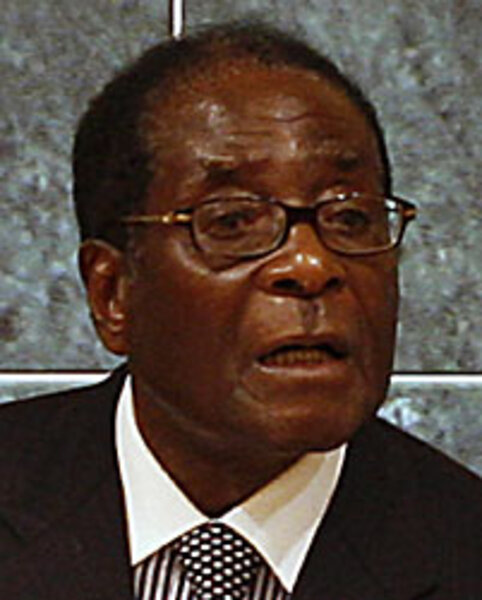

US, world influence over Mugabe limited

| Washington

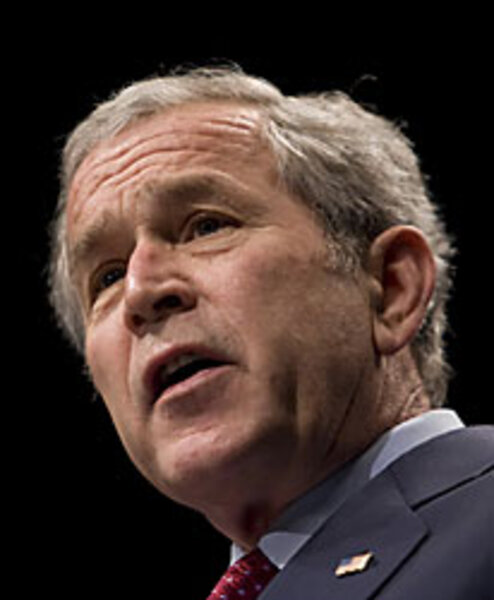

President Bush's eleventh-hour call for Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe to step down may have little realistic chance of influencing the African strongman. But it says much about the international community's failure to bring down the world's worst tyrants.

Mr. Bush this week joined British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and French President Nicolas Sarkozy in declaring that the time has come for Mr. Mugabe – one of Africa's last lions of liberation from white minority rule, but also a despot who resists democratization – to step aside for new leadership.

Zimbabwe, once Africa's breadbasket and relatively prosperous, is sinking into chaos over the failure to implement a power-sharing accord reached in September between Mugabe and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai.

On Tuesday, Bush said, "It is time for Robert Mugabe to go."

But with Bush about to leave office, the international community showing little appetite for taking a forceful stand, and the African Union shying away from anything more than dialogue to resolve the crisis, most analysts see little impact from Bush's words.

"It's good to hear this kind of declaration, because it shows the international community is with the people, but it's far from enough to make a difference," says George Ayittey, a prominent Ghanaian economist and a professor at American University in Washington. "The regime won't be moved by words."

Zimbabwe already stood on the verge of collapse, with a worsening food shortage, services at a standstill, and the economy in chaos. But now, an outbreak of cholera has affected more than 14,000 people and caused more than 600 deaths, according to the United Nations.

Members of Mugabe's inner circle of supporters say the world – and in particular the "white West" – is trying to use the cholera outbreak to impose its wishes on a sovereign country.

No mechanism to deal with dictators

But what Zimbabwe may illustrate more graphically is how ineffective the world remains at addressing the problem of entrenched dictators.

In a recent interview summing up her experience in the Bush administration, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said she was "still really appalled at the inability of the international community to deal with tyrants."

Singling out the cases of Zimbabwe and Burma (Myanmar), Ms. Rice said the world remains unable to mobilize "international will" to take on tyrants.

"Condoleezza Rice is absolutely right, we don't have a mechanism to deal with these terrible dictators," says Jeswald Salacuse, a specialist in international dispute settlement at Tufts University's Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in Medford, Mass.

The only thing likely to get a tyrant's attention is a threatening use of force, Mr. Salacuse says. But he adds that the global opposition to the American war to depose Saddam Hussein illustrates how little appetite there is for internationally imposed regime change.

"There are few things these dictators worry about, and it's not the world's disapproval," Salacuse says. "It's either intervention, or meaningful economic sanctions that really hurt."

But others cast doubt on the effectiveness of sanctions.

"History shows it's very hard to use sanctions to get a regime to change its behavior," says Randall Newnham, an expert in economic aid and sanctions as a foreign policy tool at Pennsylvania State University's Berks College in Reading. "The idea is that you make things hard for the people so that they rise up against the despot, but generally the result has been to accomplish the former but not the latter."

That's because "the clique around the leader" controls the levers of power and benefits from the smuggling and other practices that arise to offset sanctions, Dr. Newnham says.

Do smart sanctions work?

That problem has given rise to what are called "smart sanctions," he says, which are designed to hit the regime while sparing the general population. For instance, this week the European Union increased its "smart sanctions" on Zimbabwe by adding 11 names to a list of regime military and other officials barred from traveling to or dealing with EU countries.

But critics note that EU sanctions on Zimbabwe have been in effect since 2002 with evidently little impact.

American University's Dr. Ayittey says experience demonstrates that there are only two options to influence Mugabe: a concerted effort from Zimbabwe's neighbors or a threat of international intervention.

"If you had an African economic blockade, Zimbabwe wouldn't last a week," he says.

Ayittey says South Africa especially, being a crucial economic lifeline for Zimbabwe, could play an influential role in the crisis.

Yet, even though South Africa's former president, Thabo Mbeki, brokered the power-sharing deal between Mugabe and Mr. Tsvangirai, the African powerhouse country appears unwilling to apply any meaningful pressure on the regime.

Short of a tougher response from Zimbabwe's neighbors, Ayittey says it's time for the international community to "stop playing politically correct" with Africa's dictators "and their bogus accusations of white recolonization" and intervene by force – preferably by the UN declaring Zimbabwe a "protectorate" and deposing the regime.

Fletcher's Salacuse sees no chance of that happening. "The small countries in particular are worried about this, they would see it as the violation of a sovereign state," he says. "They'd say, 'If it can happen to Mugabe, it can happen to us.' "