Will Libya stalemate force US out of its back-seat role?

| Washington

As the Libya conflict appears to settle into a potentially protracted stalemate, the memory of President Obama’s demand that Muammar Qaddafi step down from power – essentially a call for regime change – is feeding a debate over what the president will or should do now to influence the outcome.

A growing number of policymakers and regional experts are concluding that a drawn-out war in the midst of a turbulent Middle East would be the worst of all possibilities. And as they do, doubts are mounting over the Obama administration’s decision to take – or at least try to take – a back-seat role among international powers involved in Libya.

Even as Libya’s rebels retreat from gains made last week and Colonel Qaddafi shows no signs of budging from his Tripoli stronghold, a debate builds over what the US should do. One side says Obama is in tune with a majority of Americans who may support the idea of humanitarian intervention, yet who are leery of any deeper involvement of the US in Libya.

On the other are critics who think America’s leadership role in the world requires more than a wait-and-see approach to crises, especially when key US national interests are at stake.

“I assert that if we had called and declared a no-fly zone early on, three or four weeks ago, Qaddafi would not be in power today,” says Sen. John McCain of Arizona. Having failed to do that – and having pulled US airpower from the fight before the battle was won, he adds – Obama should now find a way to arm the rebels, perhaps through third parties.

The US should also join France and Italy in recognizing the rebels’ transitional national council as Libya’s legitimate government, he says.

The humanitarian costs of coalition-building

Speaking at a Monitor breakfast in Washington Wednesday, the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee said Obama’s priority on building a multinational coalition before taking action gave Qaddafi time to organize his forces.

Obama wanted the approval of “every international institution except maybe the World Food Organization” before he would act, he said.

Senator McCain says he understands both the attraction of “shared efforts” and the reality that America cannot enter every crisis in the world. But he says that the irony of belated US action in this case will be a stalemated conflict that will end up imposing a bigger humanitarian burden on the Libyan people.

The humanitarian implications of a military stalemate in Libya are also prompting some regional experts to urge the US to undertake a more active, if behind-the-scenes, role.

“From a Libyan viewpoint, dragging the country into a long political and economic crisis, and an extended low-level conflict that devastates populated areas, the net humanitarian cost will be higher than fully backing the rebels, with air power and covert arms and training,” writes Anthony Cordesman, national security expert at Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, in a commentary Wednesday on the CSIS website.

A middle path between regime change and the status quo?

Mr. Cordesman says that the international political environment precludes the US, as it does NATO, from openly adopting “regime change” as its Libya policy. But he says that, given the alternative of an “unstable stalemate” in which civilians could suffer “for months or years,” something he calls a “quietly escalating regime kill” is the best option.

Among the essential elements of such a policy would be stepped-up airstrikes on Qaddafi forces and weapons, arming the rebels, sending in teams of Special Forces to guide coalition airstrikes (at Qaddafi assets and away from civilian populations), and fully enforcing United Nations sanctions to deny Qaddafi funds and supplies.

Cordesman acknowledges that Obama may have already approved some steps covertly. Indeed, administration officials quietly confirmed last week that the president OK’d dispatching CIA operatives to Libya to provide intelligence on the rebels and to help guide airstrikes.

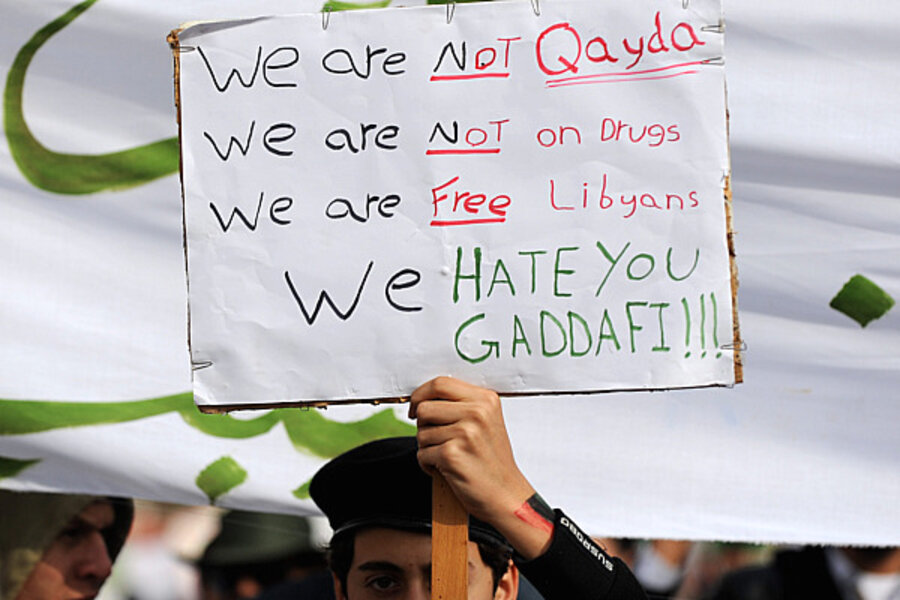

The intel on the rebels – who they are and to what degree, if any, they are infiltrated by elements of Al Qaeda – will form the basis for Obama’s next important decision concerning Libya: whether or not to arm the rebels, either directly or through third parties.