Targeting guns: a cop's new priorities

Loading...

| Baltimore

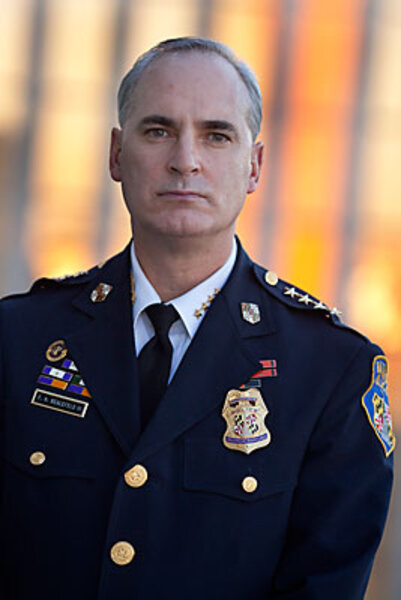

The top man in the Baltimore Police Department is standing in an alley not far from the housing complex people here call "Target City."

It's a nickname born of gun violence and could apply to more than just those low-income apartments. There are dozens of shootings in this city each week – over drugs and respect, corners and feuds, domestic violence and business deals gone bad. There are a growing number of gang shoot-outs, too, including one last summer that sent tourists diving for cover at the popular Inner Harbor waterfront area. And in August, Baltimore made national news when 12 people were wounded at a shootout at a backyard barbecue.

All of which helps explains why, here in this trash-strewn alley illuminated by the headlights of a police cruiser, Frederick H. Bealefeld III is telling the mother of three teenagers that she – not the cops – is the one who needs to deal with the fact that he just caught her boys smoking marijuana.

Backing off can be just as important as cracking down, knows the veteran of Baltimore crime fighting.

Mr. Bealefeld speaks respectfully, like an old friend of the family who just happened upon the kids' misbehavior and is letting their mom know about it. His Baltimore accent echoes hers, and he's relaxed, showing none of the aggressiveness or attitude one might expect in a section of the city where tensions between police and residents are severe. Even the boys' mother, and the family pressing up behind her in the doorway, seem taken aback that this tall white man isn't, in fact, going to hassle them.

And that's all Bealefeld: accustomed to shaking expectations. He grew up in a family full of men who wore the blue uniform, and he rose from street corner patrolman who chased down his share of drug deals and gunslingers to become commissioner two years ago. He never went to college, has lived his whole life in Baltimore, and spent 28 years on the police force. Yet Bealefeld has bucked established department policy dramatically, pushing for a new, tighter focus on guns and gun offenders, while also emphasizing improved relations with the city's black residents.

He has become known as being exceptionally blunt, a colorful character who can disarm criminals, politicians, and citizens alike. The Baltimore Sun once published a column of Bealefeld quotes turned into poetry; after losing a bet with the mayor's office over who could best run the Baltimore Marathon, the commissioner sang – badly – Whitney Houston's "I'm Every Woman" on a popular radio show. He's a regular participant in neighborhood safety walks, meets with community groups across the city, and still plays in multiple weekly ice hockey games.

But more important than the image, people here say, are the results underlying the personality: Under his leadership, Baltimore has seen the lowest homicide numbers in 20 years; nonfatal shootings are also at a decades-long low. And according to the mayor's office, the number of complaints called in against the police – in the past an almost daily event – have dropped significantly.

* * *

Earlier this decade, Baltimore tried to implement a "zero tolerance" policing policy – a strategy used to much acclaim in New York City, where officers arrested people for the most minor of violations. Get the troublemakers off the street, the theory went, and less trouble will happen; moreover, police might get tips from small-time crooks to nab the truly dangerous criminals.

In Baltimore, however, that strategy didn't make a dent: Homicides continued upward, and the historically bad relationship between police and black residents deteriorated further.

"To get one tuna, you'd get a bunch of herring, and some minnows, and eels, and all sorts of stuff you don't want," Bealefeld says using the trademark allegorical style that makes his press attaché, Anthony Guglielmi, put his head in his hands. "If sharks are the problem, then sharpen a spear and go after sharks. You don't troll through the city with a net. Because then you scoop up dolphins. And everyone loves dolphins."

He pauses, deadpan, before he breaks into a smile. But then his face turns serious, intense. There is no mistaking that this is a law enforcement officer who is exceedingly tough.

"Listen, I'm being facetious, but the analogy gets back to the core of relationships in city. And in particular African-American cities like Baltimore.... You know what I heard a lot in my 28 years here? I've gone and done search warrants, gone and done battle with guys on the street, and we're dragging these guys off and we think we've done a good deed, we think we've done something good for the community – and we hear people yelling, 'Why don't you get the big guys?' And it's like, 'The guy had a kilo in his car! What are you talking about? I think he's a big fish.' " But not to them. That's not their priority.

"You know who their priorities are? These guys who are riding around with guns who rob them every time their kids go to the store. The community – they [understand] the drugs.... They don't like them, but they're really, really worried about these guys with guns shooting their children...."

Since becoming commissioner, Bealefeld has told his officers to focus on gun offenders. And it is a point of pride to him that while murder numbers have dropped significantly under his watch, so have arrests. In 2005, police made 105,000 arrests in this city of 600,000. Last year, which had the lowest homicide numbers in two decades, the number of arrests dropped to 75,000.

* * *

So Bealefeld leaves the three teenage boys sitting on the ground in the alley under the watch of another officer and walks through the backyard to chat further with their mother. The woman looks ashen as she stands in her doorway, family members peeking around her.

She explains that the kids had slipped out of a family gathering; tonight was her mother's funeral.

"Their grandma?" Bealefeld is indignant, his eyes locked on hers, but his posture still relaxed. "They do not need to be out acting foolish. Tonight of all nights. Right now your family's grieving. You don't need any more drama. I'm going to leave them for you to take care of, OK?"

She clasps her hands in thanks, and he turns to the teens.

"You could be on your way to central booking," he says harshly. "You don't need to be going there tonight.... You need to be in the house being men. OK? And remembering your grandma. That's what I need you to do. That's what your family needs you to do."

The teens start to shuffle back into the house, heads down.

"Excuse me," the woman says to the boys, glaring. She is empowered, hands on hips, on Bealefeld's team.

"I believe a thank-you is in order."

"Thank you," they mumble toward the commissioner.

He nods to their mother, walks back toward his SUV, and continues his nighttime patrol of the city. That's the corner where a 5-year-old got shot, he points out. There's the liquor store stoop where he regularly found bodies as a homicide detective. That open lot? That used to be an open-air heroin market where the fiends lined up 30 deep to get their hits.

He muses about the teens he encountered in the alley: "By arresting a couple of kids with weed, am I affecting the crime problem? I don't think I am. The power of that family will do more good for the kids than me taking them down to baby booking [juvenile detention]. Clearly we could fill up the jails with violations of the law. But I would trade a lot of missed drug lockups for a bad guy with a gun."

He looks out at the urban landscape - rows of boarded up houses, crumbling brick and wood in a weed-laced street; occasionally a swath illuminated by the surreal blue light of a Baltimore Police Department camera.

"Guns, guns, guns," he says. "It all comes back to guns."