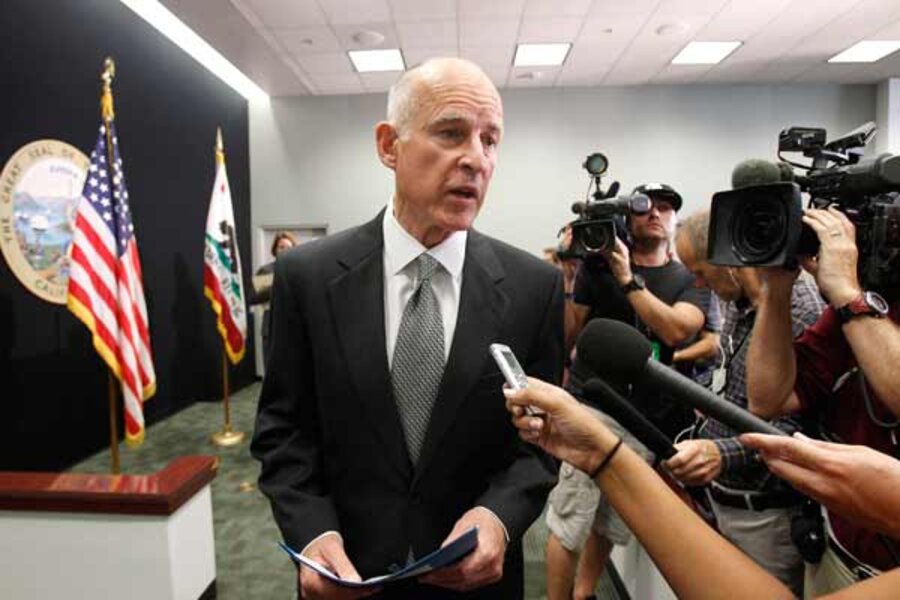

As California sues over Bell salaries, a boon for Jerry Brown

Loading...

| Los Angeles

The first legal action has been taken against the city of Bell since the L.A. Times reported in July that officials there are among the highest paid municipal employees in the nation. Located in suburban Los Angeles, the city of about 38,000 took the national spotlight when it was revealed that the city manager was being paid an annual salary of $787,637, the police chief took home $457,000 and the assistant city manager brought in $376,000.

The Times also reported that the largely poor, immigrant population was being exploited with astronomical vehicle impound charges.

California Attorney General Jerry Brown on Tuesday filed a civil lawsuit against eight former and current Bell city officials, calling for the recovery of unwarranted salaries amounting to hundreds of thousands of dollars, and calling for the reduction of pension benefits for the officials.

“What is clear is that the City Council and city administrator and other officials abused their public trust,” said Brown in a statement. “They engaged in a collaboration that [amounted] to a civil conspiracy to defraud the public.”

While Brown pushes a civil suit, the Los Angeles County district attorney is focusing on a criminal case and federal prosecutors are investigating whether the city violated the civil rights of its predominantly Hispanic population through selective enforcement of traffic laws and code violations.

Even before the investigations and legal procedures are complete, analysts are examining possible lessons from what happened in Bell.

“Note the problem of having large, non-citizen populations,” says Claremont McKenna College political scientist Jack Pitney. “In the short run, politicians actually benefit from [such situations], since smaller electorates make it easier and cheaper to hold on to power.” He says that because immigrant populations are very busy working, they often don’t pay attention to City Hall, which means they can be easily exploited.

“As local newspapers close their doors or cut back their staffs, these scandals will happen more often,” Mr. Pitney says.

Bell serves as the prime example to date of the kind of public discontent that is fueling the "tea party" movement and, if watched carefully, could provide productive answers for their issues, observers say.

“People look at this and figure, ‘if these guys in this itty bitty town are doing this, then what are much smarter guys doing in much bigger places?' ” says Frank Gilliam, dean of the UCLA School of Public Affairs.

For weeks local TV has showcased angry meetings of citizens yelling at Bell city officials, demanding to know more about their salaries and how the people had been betrayed. One positive outcome, say analysts, has been new state legislation to make it easier for residents to learn the salaries of public officials.

In addition to boosting awareness of government overreach, the Bell scandal may have provided election fodder for Brown, who is in a dead heat in the race for governor with weeks to go.

“What Jerry Brown is doing in Bell is standard operating procedure for him,” says Robert Stern, president of the Center for Governmental Studies. He's using the scandal "to promote himself but also to solve an important governmental problem.”

Mr. Stern says Brown’s “Political Reform Act of 1974” was passed by 70 percent of California voters during the Watergate scandal “and he used it to become governor in 1974.”

One irony, says Stern, is that Brown’s campaign ads talk about returning control to local governments, “yet as Attorney General, he is suing local governments for being out of control.”

Pitney says the lawsuit will help Brown keep public attention on the one key advantage he has over opponent Meg Whitman: he has a real job and she doesn’t.

“Jerry Brown is doing what office-holders usually do: leverage their official duties for maximum media attention,” says Pitney. “It won’t make much difference in November, but at least it diverts attention from his awkward comment about President Clinton.”

University of Southern California political scientist Sherry Jeffe agrees that the Bell scandal has been important to the California gubernatorial race.

“As a candidate by night, Jerry Brown, the attorney general by day, has really picked up this issue and run with it. He is getting publicity for free that Meg Whitman could not buy.” Whitman has outspent Brown by a large margin – contributing some $119 million of her own money to her campaign.