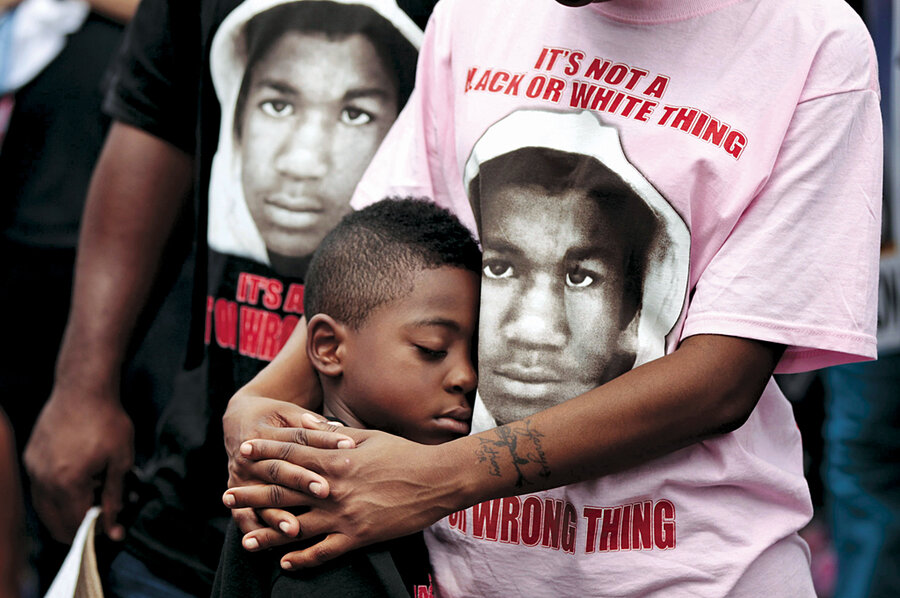

What has become clear in the weeks since unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin was shot and killed by a neighborhood-watch captain in Sanford, Fla., is that many in America, especially young people of color, feel a personal connection to aspects of the tragedy – almost as if they'd experienced some part of it themselves.

Maybe that's because they have, or because they know someone who has felt unfairly targeted. Their rallying cry, "I am Trayvon Martin," has echoed at protests across the United States, prompting renewed debate over race and justice, crime and gun laws.

Some who study such issues say the protesters have plenty of grounds for complaint.

"This is not an exceptional case except for the fact that the one who did the accosting while armed was a private citizen" rather than a police officer, says law professor Michelle Alexander of Ohio State University, author of "The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness." In New York last year, she says, city police conducted nearly 700,000 "stop-and-frisks," and 87 percent of the people stopped were black or Hispanic. About 12 percent of the stops led to arrests or summons.

High rates of unexplained stops by police, arrests, and incarcerations, she says, send "the message to young black men that no matter who you are, what you do, whether you play by the rules or not, you're going to be viewed and treated like a criminal and you're likely to wind up in jail one way or another."

Much about the Feb. 26 death of Trayvon Martin remains unclear, and both Trayvon and shooter George Zimmerman have their defenders. Mr. Zimmerman has not been arrested, having claimed self-defense under Florida's Stand Your Ground law. Two investigations – one federal, one state – will determine if that disposition will stand.

Monitor interviews with young African-American men around the US explore what it means to be young, black, and male in the US today. These interviews, of course, do not speak for a whole subset of the population. They are simply a closer look at how a few men – part of a group that sits at the bottom of almost every yardstick of economic, educational, and social well-being – perceive their role in society, and how they believe others perceive them.