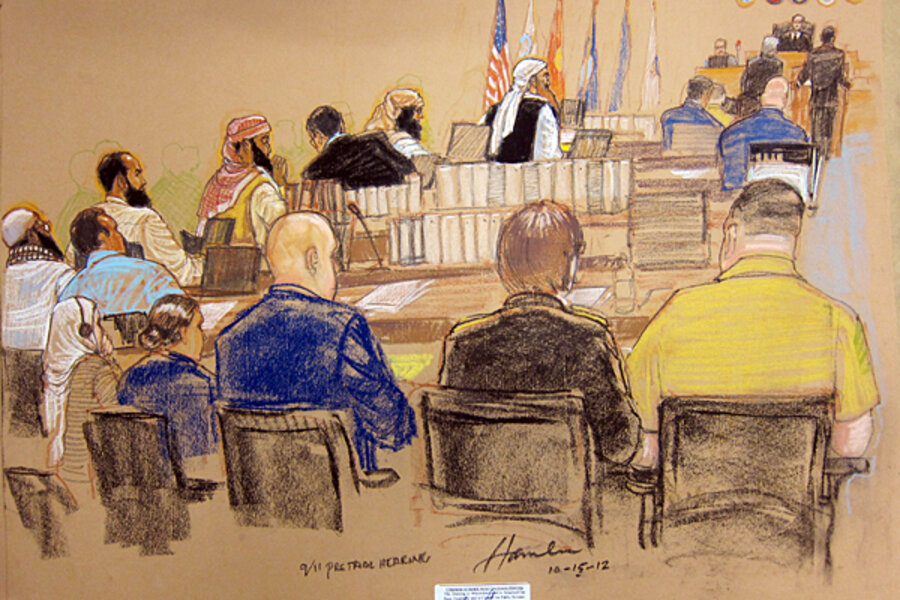

9/11 cases: Three of five Guantánamo detainees skip pretrial hearing

| Fort Meade, Md.

Alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and two of his codefendants decided on Tuesday to skip a day-long hearing at their terrorism conspiracy trial at Guantánamo.

The action came a day after a military judge ruled that the defendants would not be required to attend the military commission proceedings.

In addition to Mr. Mohammed, codefendants Ali Abdul Aziz Ali and Mustafa Hawsawi decided not to attend Tuesday’s session.

There was no indication in court why the three decided not to attend, although Mr. Ali’s lawyer said on Monday that Ali’s father had died recently in Kuwait and that his client was in mourning and did not wish to attend.

The judge, US Army Col. James Pohl, asked the government for an account of how each of the detainees communicated his decision not to attend.

A Guantánamo security official, whose name and position were blocked from public release, said she had personally followed a procedure established by Judge Pohl on Monday. Each of the three defendants signed a formal waiver of their right to be present in court.

The unnamed official said she knelt down in the hallway outside Mohammed’s cell to be able to speak to him face to face through a slot in the door. She said Mohammed said he wished to attend court. But she added that he changed his mind after being transported to the holding cell near the courtroom.

The two other detainees remained in their cells at the detention camp.

The judge found that all three of the defendants had voluntarily waived their right to be present. His formal finding was entered into the court record, in part to insulate the trial and any potential conviction from an appeal claiming the defendants were improperly excluded from their trial.

In court on Tuesday were Walid Bin Attash and Ramzi Bin al-Shibh.

Lawyers for all five of the accused continue to defend their clients whether the defendants are in court or not.

The developments came on the second day of five days of pretrial hearings to address a range of legal issues to set the stage for the military commission trial of the five Al Qaeda defendants.

The five are accused of participating in a terrorism conspiracy that destroyed the World Trade Center, damaged part of the Pentagon, and killed nearly 3,000 on Sept. 11, 2001.

The hearings are being conducted in a specially built high-security courtroom on the US Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. In addition to reporters present in court, other members of the media are monitoring the proceedings via a video feed at Fort Meade, Md.

In other action, Judge Pohl ruled that detainees would be permitted to decide for themselves what they wished to wear while present in court.

Defense lawyers had complained that security officials in charge of the detention facility at Guantánamo had barred the defendants from wearing certain articles of clothing in court. The officials had refused to allow a detainee to wear an orange jump suit and refused to allow other detainees to wear camouflage jackets and vests.

A government lawyer, Marine Maj. Joshua Kirk, said the detention officials were trying to uphold the dignity and decorum of the military commission process. He said officials were concerned that detainees might try to use their clothing for propaganda purposes to convey that they were legitimate combatants rather than terrorists.

He also said security officials objected to detainees wearing any clothing with pockets in which contraband or weapons could be concealed.

One of Mohammed’s lawyers, Army Capt. Jason Wright, said the Geneva Conventions recognized that certain paramilitary and resistance groups are entitled to some legal protections when they wore clothing on the battlefield that distinguished themselves as combatants.

Wright noted that Mohammed had been part of the Afghan Mujahideen that fought the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. He added that the effort received the covert support of the United States government.

“Did they have a uniform?” Pohl asked.

“Mr. Mohammed wore a uniform,” Wright answered.

“The fact that he chose to wear parts of some uniform doesn’t mean it is a uniform,” the judge said.

Wright replied that even wearing a military-style jacket would qualify as a uniform under the Geneva Conventions.

The defense lawyer added that if pockets were a security concern they could be sewed over or removed.

Pohl said that he would not attempt to dictate to security officials what the detainee must wear while in the detention camp. But he said it was up to him to decide how detainees would be dressed while in his courtroom as defendants. Pohl ruled that the defendants would be free to come to court in prison garb, if they so chose, provided it was the same kind of detention clothing they routinely wore.

In addition, he approved the defense request to allow the defendants to wear camouflage jackets or vests to court. But the judge said the defendants would be barred from wearing a uniform or portion of a uniform worn by any branch of the American military.