Zimmerman jury of peers is jury of (mostly white) women

| ATLANTA

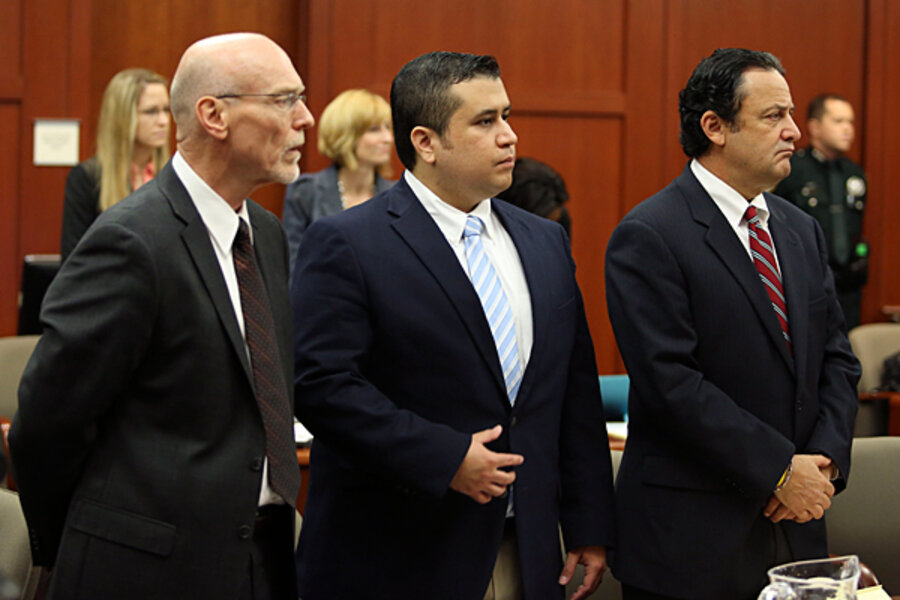

An all-female and mostly white jury will decide whether volunteer watchman George Zimmerman committed second-degree murder when he shot and killed an unarmed black teenager, Trayvon Martin, on a rainy Florida evening in February 2012.

Debate around the high-profile case has swirled around the stereotyping of young black men, defense strategies to raise questions about Martin's character, crime scene photos that suggest a violent struggle took place, and furious courtroom arguments over whether to allow testimony by audio experts regarding who emitted a brief shriek in the background of a 911 call the moment before a shot rang out.

But now the mostly middle age and older female jury – all white, except one Hispanic woman – have to attempt to set aside what they have heard about the case and move beyond their own attitudes and beliefs in order to zero in on whether the killing constituted murder, as the state contends, or was a tragic result of legitimate self-defense.

The gender equation could become a major factor in a case that, at its core, touches on the lengths to which people can go to defend themselves, their homes, and their neighborhoods against threatening strangers – and on whether defensive impulses sometimes simply hide racism.

“Women tend to be more reflexively opposed to the use of violence generally, and also be aware that most violence is perpetrated by men, for just or unjust reasons,” says Doug Keene, a jury consultant in Austin, Texas, who has been following the case.

The jurors include one woman who has been a victim of a crime and one woman who has previously been arrested. Some know intimate details of the case, another one claims to have barely heard about it before being picked for jury duty. The jury includes one young woman, several middle-aged women, and several retirees. While there were seven potential black jurors in the final round of 40 possible jurors, none were picked.

One of the women, the youngest, says she used the shooting in Sanford, Fla., as an example to her two adolescent kids not to go out at night.

Two of the four alternate jurors, however, are men, including a white man who says his teenage son wears hoodies, and a Hispanic man who is passionate about arm-wrestling.

The case has been portrayed as a tragic prism for the state of US race relations. One widely held suspicion is that the Sanford police would not have released, as they did Zimmerman, a black man who shot an unarmed white teenager in the same manner.

A special prosecutor indicted Zimmerman 44 days after the shooting in the wake of nationwide rallies by hoodie-wearing protesters. Martin was wearing a gray hoodie as he returned from a store with a bag of Skittles, an outfit that apparently helped Zimmerman peg the boy as “suspicious” in a neighborhood that had endured a spate of petty thefts, carried out largely by young, black perpetrators.

Another potential legacy of this particular jury, experts say, could be how it comes down on the use of guns in self-defense outside the home, and how that principle applies to a situation in which a volunteer watchman follows someone they believe to be suspicious, as Zimmerman did. Lawyers questioned the jurors extensively about their views on guns and gun ownership.

One of the jurors said she used to have a concealed weapons permit, but let it lapse. Another one said her husband owns a gun. Prosecutors attempted to strike both jurors, but were denied.

No matter the age, race, gender or beliefs of the jurors, however, jury experts like Mr. Keene believe the panel will set aside the political and policy debates in order to focus on the last moments of Trayvon Martin’s life.

“I talk to a couple of thousand jurors a year, and 99 percent of them show an astonishing determination to discern the truth of a dispute,” Keene says. “Their commitment to separate the wheat from the chaff is amazingly impressive, whether it’s a straightforward matter or the most incredibly complex and arcane dispute.”