Feds target 'stand your ground' laws, but what can they do?

Loading...

| Atlanta

Picking up on rumbles of frustration, even outrage, about the George Zimmerman verdict, top US officials are insisting that America, and perhaps its federal government, need to take action to honor the memory of Trayvon Martin, the unarmed teenager whom Mr. Zimmerman killed.

For now, President Obama has been somewhat circumspect in his reaction, suggesting Americans search their own hearts for ways to make sure that Trayvon’s death isn’t repeated.

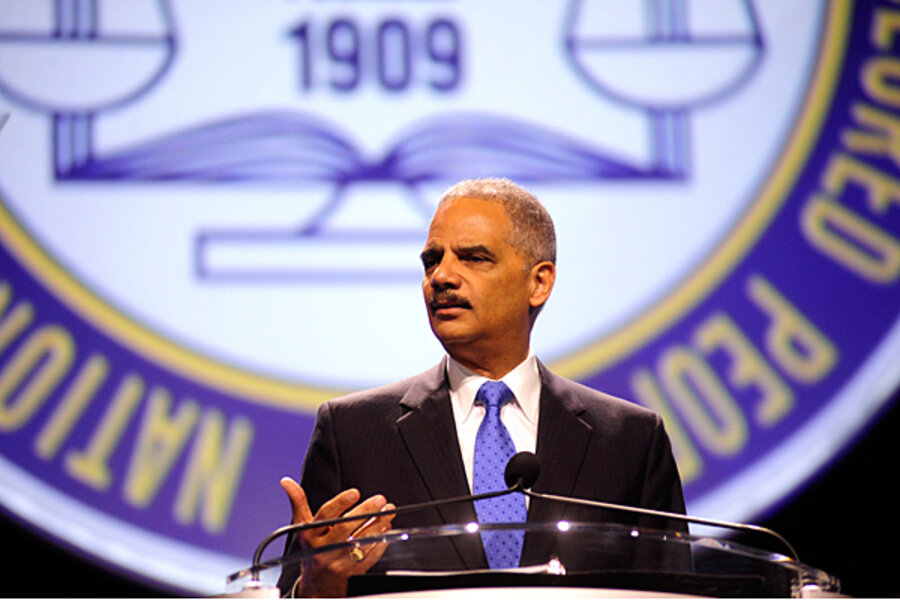

Attorney General Eric Holder has been more specific in a critique, focusing on a new breed of self-defense laws used to arrive at the verdict. “It’s time to question laws that senselessly expand the concept of self-defense and sow dangerous conflict in our neighborhoods,” he said Tuesday at the NAACP’s annual convention in Orlando, Fla.

A US civil rights watchdog, meanwhile, is redoubling its efforts to determine whether these so-called stand your ground laws disproportionately victimize black people.

Mr. Zimmerman was acquitted on Saturday after a 16-month national ordeal that began when he killed Trayvon – whom he had profiled as a criminal and followed – after Trayvon punched him and the two struggled. But for a sizable portion of America, the verdict failed to assuage suspicions that by letting Zimmerman off, Florida ultimately whitewashed a civil rights violation.

“We don't need consolation, we need legislation,” the Rev. Al Sharpton, a civil rights leader, said after the verdict. “And we need some federal prosecution."

Still, the question remains: What, if anything, can the federal government really do, especially since the Department of Justice has begun to signal that it’s not likely to charge Zimmerman with a federal hate crime?

In truth, there may be little that Messrs. Obama or Holder can do, in particular about stand your ground laws. Neither the Congress nor the executive branch can outright force states to change their laws, and courts have been skeptical about attempts to strike down stand your ground laws, even when there’s evidence of systemic racism and discrimination.

“I kind of feel for the Justice Department: They’re under tremendous pressure to do something,” says Brannon Denning, a law professor at Samford University in Birmingham, Ala. “The attorney general can talk all he wants about [reexamining stand your ground laws], but the US government has very little power to actually effect change in states that have them.”

Stand your ground legislation, which was pioneered in Florida, expands the so-called castle doctrine – where people have no duty to try to retreat from danger in their own homes – to public spaces. More than half the states now have similar laws on the books.

While the defense in the Zimmerman trial did not invoke Florida’s 2005 Stand Your Ground law directly, Judge Debra Nelson included a definition in her instructions to the jury, writing that if Zimmerman “was attacked in any place where he had a right to be, he had ... the right to stand his ground and meet force with force” if he reasonably believed death or grave bodily harm were imminent.

At least one Zimmerman juror pointed to the Stand Your Ground law as a key factor in the jury’s verdict.

Then again, even some of those who support a more robust debate on stand your ground question whether tying that debate directly to the Zimmerman verdict is the right approach.

Potential reform of stand your ground “is a very complex policy discussion that has to take place at the state level for the most part,” Stanford civil rights law professor Richard Thompson Ford told CBSNews.com on Wednesday.

Some studies have suggested that blacks are far less likely to succeed in so-called justifiable homicide cases where self-defense is invoked, especially when the victim is white.

An investigative series in the Tampa Bay Times last year found that defendants are more successful in Stand Your Ground defenses when the victim is black. According to the study, 73 percent of defendants who killed a black person were acquitted, compared with 59 percent of defendants who killed a white person and then claimed self-defense.

But this week, The Daily Caller, a conservative publication, reported that in Florida, blacks on the whole invoke Stand Your Ground at a higher rate than whites and have a higher rate of success with the defense than whites do.

More broadly, studies have been decidedly mixed as to whether stand your ground laws exacerbate violence or are of ultimate benefit to public safety.

Such disparate findings are part of the problem when seeking judicial relief. Also, courts tend to limit trend data when prejudice can’t be proved by the facts in the particular case on the docket.

The bar for federal intervention in state affairs is whether a particular law “disproportionately impacts minority groups,” says Clayton Cramer, a gun-rights historian in Horseshoe Bend, Idaho. Citing The Daily Caller report, he adds, “The problem is that this law has disproportionately benefited a minority group, which demolishes” the legal standing.

To be sure, inquiries are ongoing into the Trayvon Martin case, most notably an investigation of stand your ground laws by the US Commission on Civil Rights. This civil rights watchdog group, appointed by the president and Congress, has no binding power, but it can investigate alleged civil rights abuses and make recommendations about how to address inequities.

The Trayvon Martin case “opened up a nationwide inquiry into the appropriateness and efficacy of Stand Your Ground laws,” said Michael Yaki, one of the commissioners. “To honor Trayvon and his family, we will continue this inquiry with resolve and renewed purpose.”

But other civil rights law experts suggest that Department of Justice officials may better serve the country by channeling the passion and outrage about the Zimmerman verdict not into trying to change state laws or prosecute Zimmerman again, but into exercising the powers they have been given by Congress – specifically, oversight of state institutions like schools and law enforcement.

Darren Hutchinson, a law professor at the University of Florida in Gainesville, points to studies that show, for example, how Florida school districts funnel disproportionate numbers of black students into the criminal justice system. When police in Gainesville were confronted with such a study, the reply was not denial, but, “What can we do to change it?” Professor Hutchinson says.

“Proving that Zimmerman killed Trayvon with racial motivation beyond a reasonable doubt is going to be impossible, since there’s no explicit evidence of racial discrimination,” Hutchinson says. “Focusing on Zimmerman isolates the problem.”

But challenging systemic patterns of discrimination in schools, he says, could “bridge Trayvon’s youth with the law enforcement piece, and it would be a great, symbolic gesture with very practical implications on how to bring federal and state entities together, and creating change for the next generation of Trayvon Martins.”