Montana rape case: Was 31-day sentence for teacher illegal?

Loading...

Montana's attorney general has asked the state Supreme Court to further punish a teacher who served a month in jail for raping a 14-year-old girl. The girl later committed suicide.

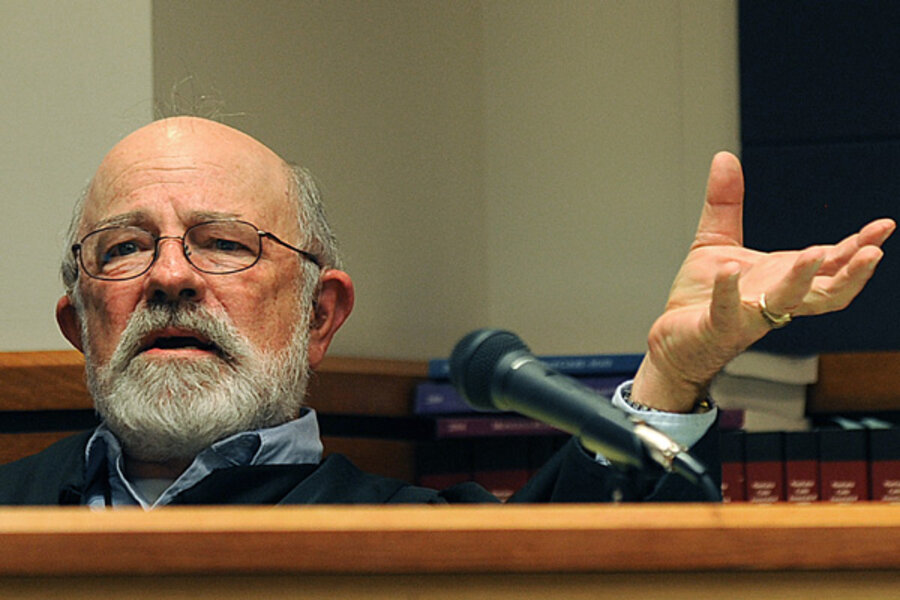

The case drew national attention not just for the short sentence, but also for comments made by District Judge Todd Baugh of Billings. In explaining the sentence, Judge Baugh said in August that the girl was “older than her chronological age” and “as much in control of the situation as was the defendant.”

The appeal filed Friday by the state attorney general's office took issue with Baugh's reasoning, stating "there is no legitimate hypothetical that allows blame to be placed on a 14-year-old student who has been victimized by her 47-year-old teacher.”

The document argues that Baugh misapplied state mandatory minimum-sentencing laws and that the Supreme Court should re-sentence the teacher, Stacy Rambold. The attorney general's office suggests a 20-year sentence with 10 years suspended.

The case mirrors another in Alabama and sheds light on the complicated world of mandatory-minimum sentencing, where long sentences can, in some cases, result in no jail time whatsoever.

In the Montana case, Mr. Rambold was originally charged with three counts of raping Cherice Moralez, who was a student in his high-school technology class in Billings. In 2010, Cherice committed suicide while the case was still pending. Without her testimony, which was seen as crucial to the case, prosecutors offered Rambold a deal: admit to one count of rape, which would be dismissed after three years if he completed sex-offender treatment.

But Rambold violated his deal by having relationships with women that he kept secret, which brought the case before Baugh. The prosecution argued for 20 years, 10 suspended, but Baugh opted for 15 years with all but 31 days suspended.

Judges often have wide latitude in sentencing, even under mandatory minimums.

"Why give so much discretion to judges?" writes Danny Cevallos, a legal analyst for CNN on the CNN website. Citing Alabama, he notes that sentencing rules "cite skyrocketing costs associated with actual confinement and call attention to prison overcrowding. That prison overcrowding leads to uncertainty: In other words, the judges don't know that the prison can even accommodate their sentence, so they might as well mete out a sentence that can actually be carried out."

Mr. Cevallos also makes another point: "Like it or not, most sex offenders will eventually serve their sentences and be back on the street. Given the risk of repeat offenses, rehabilitation of these felons could be the most critical factor in protecting society."

In Rambold's case, he has had to reenter sex offender treatment and cannot have any contact with minors unless they are with an adult who knows about his conviction and is approved by his probation officer, Reuters reports.

According to the report, he can go to parks, shopping malls, schools, movie theaters, or other places where children are likely to gather only if he goes with an adult chaperone and his probation officer gives him permission. He also can't go on the Internet without approval.

Similar restrictions have been placed on Austin Clem of Alabama's Limestone County, who was convicted of raping Courtney Andrews three times – twice when she was 14 and once when she was 18. Mr. Clem was sentenced to 20 years in jail on a first-degree rape change and 10 years each for the two second-degree charges – all to be served concurrently. But similar to Rambold, all that time was suspended and Clem was required only to serve three years in a community corrections program and three years of probation. The result was no jail time.

Also similar to the Montana case, a local district attorney last week appealed the sentence to the state Court of Criminal Appeals.

Clem's attorney told CNN that the requirements for the community corrections are so tough that they amount to house arrest. The attorney says the relationship should not have happened because Clem was married and Andrews was a minor, but it was consensual. Ms. Andrews, now 20, was good friends with Clem's wife and kept going to his house even after the initial attacks, he said.

"It doesn't appear from her actions that she was saying 'no,' " he said.

But Andrews, who told a friend to tell her parents after the attack when she was 18, was "baffled" by the sentence. At age 14, she told CNN, she could not legally consent to anything.

The Montana attorney general's office appears to be taking a similar view. "The circumstance of a 47-year-old teacher having sexual intercourse with his 14-year-old student is precisely such a circumstance warranting a mandatory minimum sentence," the court document said.

In response to the national outrage over his decision, Baugh, the Montana judge, tried to change his own sentence in September, but the state Supreme Court ruled he could not. The current appeal, the state attorney general says, is the legal way to amend the sentence.

The Supreme Court has not announced any schedule to take up the appeal.