Court halts Oklahoma executions: why lethal injection is now so controversial

The controversy surrounding lethal injection intensified Monday after the Oklahoma Supreme Court halted the executions of two inmates, saying the men have the right to challenge the secrecy surrounding the drugs the state intends to use to kill them. Their execution date was originally April 29.

The case is highlighting the legal uncertainty surrounding the lethal injection process. Many states are now refusing to reveal where the drugs originate and what is in them. Capital punishment foes say that violates the constitutional rights of inmates because it could lead to cruel and unusual suffering.

1. Why is there a problem now?

There is a supply shortage. In 2011, the European Union restricted the export of eight drugs that are licensed for use for lethal injections in the US, including sodium thiopental and pentobarbital. EU guidelines call for the "universal abolition" of the death penalty. Since then, supplies here have dwindled, which has sent US authorities looking for alternatives.

2. How have states compensated for the shortage?

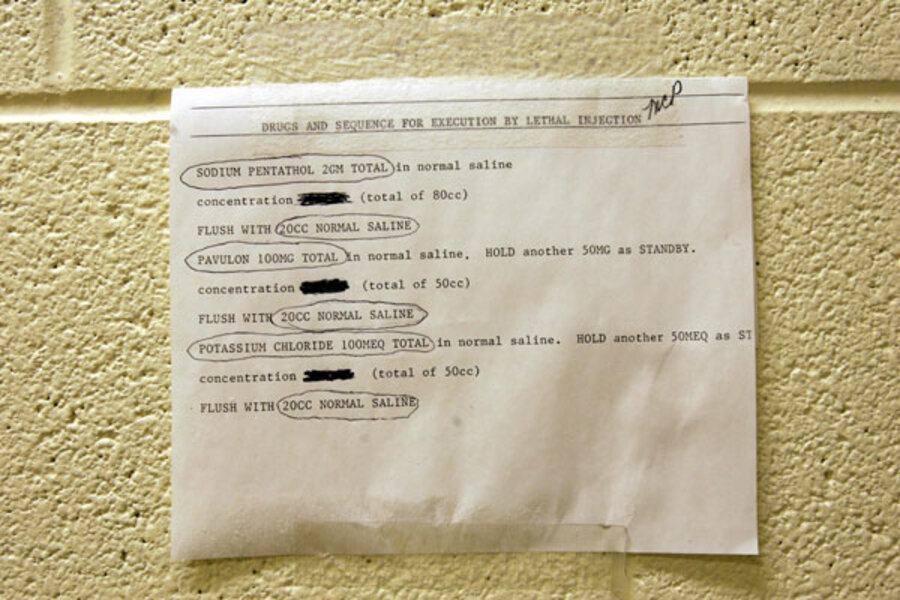

Therein lies the mystery. Many states have resorted to creating their own batches of drugs intended for use in lethal executions, but they will not divulge where the drugs originated, or, in some cases, what drugs are being used.

There is also talk in some quarters of bringing back former methods of execution, such as firing squads, the gas chamber, hangings, or electrocutions. Legislators in Wyoming, Missouri, and Virginia have recently considered of resurrecting such methods. In fact, Virginia put a man to death by electrocution in 2013; the bill recently considered by the Senate would make electrocution the default method of execution if no drug cocktail is available. The bill was shelved until next year. Electrocution remains a choice in eight states.

Three states (Arizona, Missouri and Wyoming) still allow gas chamber executions, while three other states (Delaware, New Hampshire, and Washington) still allow hangings. In Oklahoma, death row inmates can still face a firing squad. The last person killed by firing squad in the US was in 2010 in Utah, although the state has since phased out the practice.

3. Why does the secrecy matter?

Two reasons: public safety and the concern over cruel punishment.

Lawyers for death row inmates argue that US suppliers are not as regulated as the major drugmakers in the EU, and therefore they pose a threat to public safety. For example, contaminated injections from a Massachusetts facility in 2012 caused a meningitis outbreak, killing 64 people and sickening hundreds.

They also say use of supplies from unknown sources creates questions about the purity and potency of the drugs, and that may violate the US Constitution’s provision for preventing cruel and unusual punishment. In Ohio, for example, a death row inmate took 26 minutes to die – the longest on record in the state – after injected with an untested cocktail of drugs this January.

4. How many states have temporarily halted at least one execution?

Along with Oklahoma, executions in Louisiana and Ohio were delayed this year due to the issue of unregulated drug supplies.

Some states, including Alabama, have rejected bills designed to shield the names of pharmaceutical suppliers to state prisons. Beyond the constitutional concern over cruel punishment, the drug issue has also created legal problems for states as more families of inmates are emboldened to pursue legal action. For instance, the family of the Ohio man executed in January is suing the state because he appeared to be convulsing for minutes after his injection. The lawsuit also targets the drug manufacturer, saying it illegally sold the drug knowing it would be used for an execution.

The potential for legal trouble is making many US suppliers nervous and could further diminish the supply for executions: An Oklahoma supplier refused to sell drugs to Missouri in February for an execution, for example.

5. Could the US Supreme Court resolve this issue?

Likely not. To date, the US Supreme Court has refused to weigh in on the issue.

Earlier this month, the high court rejected a case in Texas regarding whether states should disclose details of their lethal injection process. That stance affirmed a 2008 ruling that said states have proven to have safeguards to ensure death row inmates will not suffer significant pain.

“Simply because an execution method may result in pain, either by accident or as an inescapable consequence of death, does not establish the sort of objectively intolerable risk of harm that qualifies as cruel and unusual,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion.