How Tsarnaev lawyers are pushing judge during jury selection

| Boston

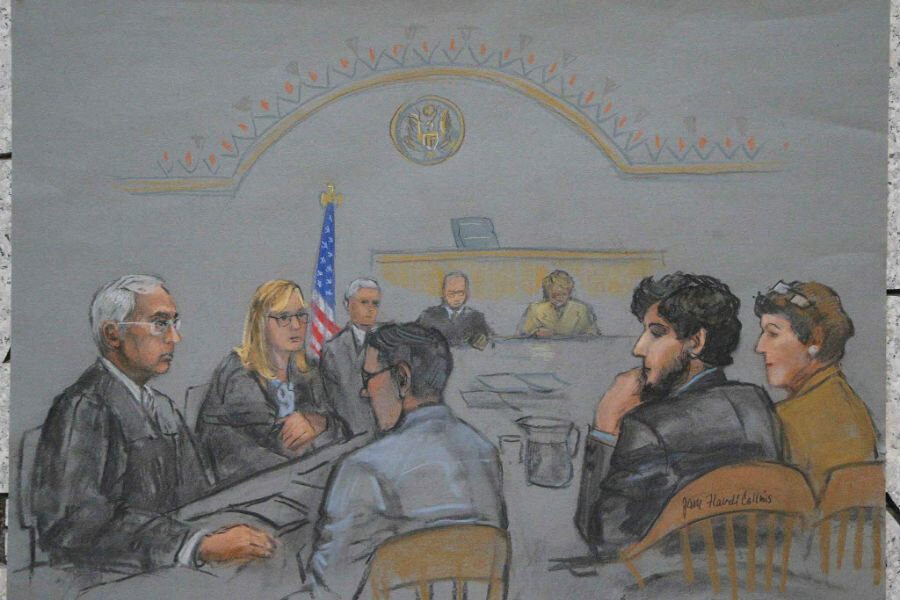

The second phase of jury selection for the trial of accused bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev began Thursday.

Twenty potential jurors came to the US District Courthouse in South Boston to face individual questioning from Judge George O’Toole, in the presence of lawyers for the defense and prosecution and in the presence of Mr. Tsarnaev himself.

Tsarnaev’s defense team voiced an early opposition to the judge’s line of questioning, with defense lawyer David Bruck asking for the judge to ask more specific questions relating to the charges against the defendant, how the specifics of the case impact their thoughts on the death penalty and Tsarnaev’s possible guilt, and how perceived public pressure – and Tsarnaev’s presumed guilt among the public – could influence them.

“Our question is not about penalty, it’s about guilt, I think that’s where rubber hits the road,” Mr. Bruck told the judge. “If [Tsarnaev] is found not guilty everyone would have to go home, they’d have to go home and face people and face up to that.”

“There would be such an explosion of outrage if that were to be allowed to happen,” Mr. Bruck added. “I think it’s critical for the court to ask [jurors] to imagine that, and it’s critical for them to think about what people would think of them.”

“Can these jurors really presume this man innocent? Or is it, ‘We all know he’s guilty so let’s get on to the penalty phase?’ ” Bruck added. “We’re supposed to have a fair trial, and the trial isn’t supposed to be over already.”

Judge O’Toole replied that such hypothetical questions “are troublesome because they don’t necessarily provide reliable answers.”

The judge added that the preliminary questionnaires jurors filled out last week address Bruck’s questions.

“The place I do agree with you is we have to look at if the person is favorable to the death penalty and also if the person is favorable to an alternate possible outcome,” O’Toole said.

O’Toole did start asking each juror whether they would, as required by law, demand that the government prove Tsarnaev’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt, or whether their preexisting biases would shift the burden onto the defense to prove Tsarnaev innocent.

The day served as a preview for what the next few weeks of the trial could involve. Media were not allowed in the courtroom, instead watching proceedings through a spotty video feed from two overflow courtrooms.

The challenge of finding even 18 people from the hundreds of potential jurors remains significant, based on the first 20 questioned at the courthouse Thursday.

Several jurors questioned Thursday were asked to explain inconsistencies and contradictions in their questionnaire answers. Others struggled to define their feelings on the death penalty. Some confessed to changing their minds on some answers between when the filled the questionnaire out last week and today.

“That’s what changed since filling out the questionnaire,” one juror told the judge. “I just think it’s completely wrong to kill another man.”

“I wrote [on the questionnaire] that I wasn’t religious,” the juror added. “This whole process has made me more religious, I just can’t vote for the death penalty.”

Another potential juror explained discussing the case with his roommates.

“I live with several other males my age, very testosterone-driven household,” the juror said. “They think that it’s very cool and they very much want me to sentence him to death.”

“Would you be able to make up your own mind or make a decision because of [your roommates]?” the judge asked.

“I would sentence [Tsarnaev] to death but not because of them,” the juror replied.

The judge pressed another juror who admitted not being willing to impose the death penalty.

“You would never impose death penalty?” he asked. “Or it would take a lot to get you to impose the death penalty?”

“If it was my child [who’d been killed] I could do it,” the juror replied.

“What if it was somebody else’s child?” the judge asked.

The juror paused for a moment, then said, “I wouldn’t want to do it, no.”