Supreme Court to examine if Texas districts violate one person, one vote

| Washington

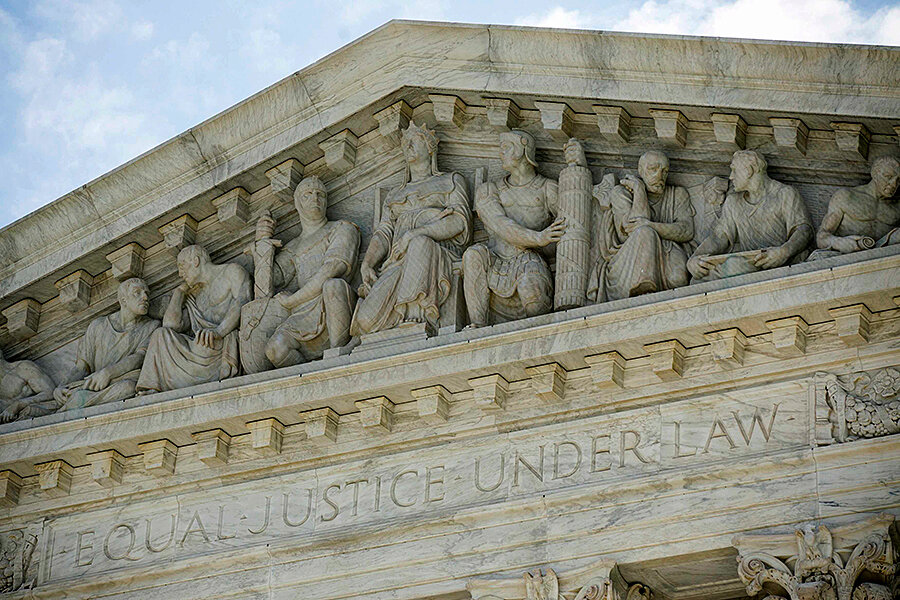

One of the cornerstones of American democracy is the principle of one person, one vote.

But what happens to that principle of equality in voting if lawmakers rely on a state’s total population, rather than eligible voters, when drawing voting districts?

That’s the issue the US Supreme Court agreed on Tuesday to examine in a legal challenge to state Senate districts in Texas. The case will be set for briefing and argument in the court’s next term, which begins in October.

The case involves a lawsuit filed by two Texas voters, Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenninger, who argue that their voting districts had been drawn unfairly because they include a larger number of eligible voters than other districts in the state.

Texas has 31 state Senate districts, each with about 811,000 people. Since the total population in any given district can include large numbers of ineligible voters – such as noncitizens and children – the actual number of eligible voters in each district can vary greatly.

In his brief urging the high court to take up the case, appellate lawyer William Consovoy argued that under a redistricting method embracing a total population approach, it would be permissible for Texas lawmakers to draft 30 new Senate districts each containing only one eligible voter (among many ineligible voters), with all other Texas voters packed into the 31st district.

“The constitutionality of that radical proposition clearly is a substantial federal question,” Mr. Consovoy wrote.

In defending the state’s voting districts as currently configured, Texas Solicitor General Scott Keller said the Supreme Court has permitted states to use total population to apportion legislative seats.

“Plaintiffs presume that the Equal Protection Clause requires states to apportion their legislative districts based on a particular measure of population,” Mr. Keller said. “But this court has recognized that states have a choice among multiple apportionment bases; it follows that the Equal Protection Clause does not mandate any particular apportionment base.”

There is no unsettled question for the high court to examine, Keller added.

The challengers disagree.

Ms. Evenwel lives in a mostly rural district in which roughly 584,000 citizens are eligible to vote. In contrast, there are only 372,000 eligible voters in a neighboring urban district.

The discrepancy means that voters in the urban district have more voting clout than voters in Evenwel’s rural district. And that, Evenwel’s lawyers argue, is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause’s guarantee of one person, one vote.

“We are grateful that the justices on the Supreme Court have agreed to hear our case,” Evenwel and Mr. Pfenninger said in a joint statement. “It is to be hoped that the outcome of our lawsuit will compel Texas to equalize the number of eligible voters in each district.”

The case was brought by a group based in Austin, Texas, the Project on Fair Representation. The group is run by Edward Blum, who has been active in several high court cases involving voting rights, equal protection, and affirmative action.

The case is Evenwel v. Abbott (14-940).