How to save kids from ISIS? Start with mom

| Washington

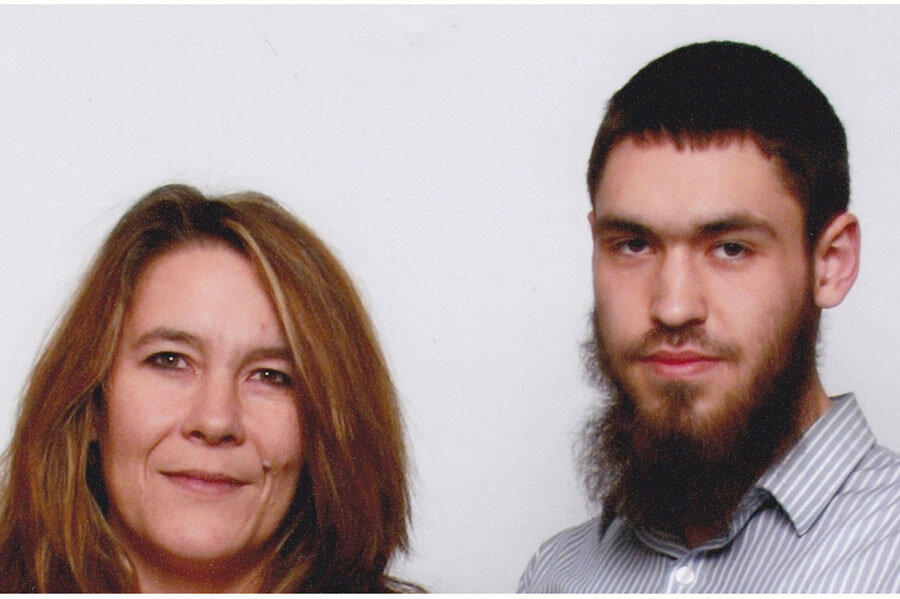

Christianne Boudreau never suspected a thing.

The mother from Calgary, Canada, was pleased when her oldest son developed a deep interest in Islam. Damian had struggled through bouts of depression and suicidal thoughts, and Islam seemed to fill a void. So she didn’t object when he announced plans to travel to Egypt to study Arabic.

What she didn’t know was that “Egypt” was just a cover story.

After her son’s departure, Canadian intelligence officers arrived at Ms. Boudreau’s front door. They told her Damian had been under surveillance for two years and that they believed he had joined an extremist group and was fighting in Syria.

In retrospect there were hints, Boudreau acknowledges, but nothing concrete pointing to her son’s growing radicalization.

Later, she received the one message from Syria she most dreaded. Her 22-year-old son, a foreign fighter with the Islamic State group, was dead.

Boudreau was both devastated and furious. She thought back to the two years intelligence agents spent watching day after day as her son was selected, groomed, and eventually radicalized into a jihadi warrior.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” she asked the agents.

Boudreau has never received an adequate response.

In coping with her loss, she decided to reach out to others to provide the help and support she never received. The result is a program called Hayat Canada, which is designed to provide family-based intervention services to mothers, fathers, and other family members struggling with a loved one who is radicalizing toward violence and extremism.

Boudreau set up the organization initially for families in Canada. But desperate parents in the United States started calling for help, too.

The idea is to empower families to launch their own intervention to free a loved one from the tightening grip of extremism before it is too late.

Such intervention programs have been operating for many years in Europe, where the foreign fighter recruitment problem is significantly larger than in the US and Canada. But now, given the Islamic State’s increasingly effective use of social media for recruiting, the number of individuals in America showing signs of radicalization is climbing.

Although there have been a few pilot programs exploring innovative ways to counter violent extremism, for the most part US officials have relied on aggressive surveillance and law-enforcement operations to fight Islamic radicalization.

That means parents who suspect their child may be in the process of radicalizing face a difficult decision. If they remain silent, their son or daughter may leave for Syria forever. The other alternative is to notify the authorities. But that would likely result in a long prison term.

'It is better to have them in prison alive'

Boudreau knows the choice she’d make had she been given the opportunity. “It is better to have them in prison alive ... than it is to have them go to Syria and be killed,” she says.

But Boudreau and other experts emphasize that the fight against radicalization does not have to be an either/or choice between prison or death. Families can take action themselves.

Boudreau’s Hayat Canada program is based on the research of Daniel Koehler, director of the Berlin-based German Institute on Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies. Mr. Koehler also has organized an international network of mothers who have lost sons and daughters called Mothers for Life.

His idea is that Islamic State recruiters are operating largely unopposed in their efforts to identify and radicalize vulnerable men and women in Western countries.

“What I am doing is leveling the playing field, building up an opponent where so far there was no opponent,” he says.

In effect, Koehler, Boudreau, and other counselors serve as advocates for the family – specialists trained to help families pull a son or daughter back from the brink and into the protective embrace of the home and community.

“I would look at the family, figure out the individual driving factors for the radicalization, and then I would bring in external experts or others,” Koehler says, describing his process.

“For example, if the family member is experiencing bullying in school or treatment with disrespect, or needs to find a job, education, anything like that, I would talk to the teacher, talk to the head of the school, or talk to the employer and try to investigate everything that is driving the radicalization.”

At the same time, Koehler seeks to introduce new positive emotional relationships – individuals the son or daughter can respect and look up to. Most important, such mentors or role models can help show that it is possible for a Muslim to live in peace and to have respect for other faiths in the West, he says.

At least that’s the plan. Recruiters for the Islamic State group are following their own strategy.

“They have recruiting manuals that are so sophisticated that the only thing we can do is build up the family or the social environment as a counterforce,” Koehler says. “That is the only way we can succeed.”

The recruiting manual, which is available online, includes a checklist to help assess whether the target has been adequately groomed for the next stage. They use grievances against the West, perceived anti-Muslim discrimination, and the religious duty of Muslims to defend the newly formed caliphate.

“It is all about gaining trust, building a relationship, and then slowly distancing the recruit from his or her family, creating that kind of frustration against the West,” Koehler says.

“It is about creating the need, the necessity to come to Syria to fight and do something about the injustice in the world and fight for freedom and honor,” he says. “They do this every day with thousands of recruits.”

In response, the first thing Koehler does when he sits down with a new family is conduct a violent extremism risk assessment. And he says he tries to gain a “gut feeling” about how the case may evolve.

Koehler always warns the family up front that there may come a time when they will have to admit defeat and notify the authorities.

He stresses that he will not take any action alone behind the family’s back. It is better that he and the family do it together, he says.

“I’ve had many families calling me directly, saying, ‘Can you please do something, put him in jail, because I would rather have him in prison in Germany than dead in Syria,’ ” Koehler said.

Many parents in this situation don’t trust the authorities. That’s when the counselor’s presence is essential. “I am moderating that,” he says. “What I am doing is I am opening up space for trust and communication where before that nothing was there. They were simply treating each other as opponents,” he says of the family and the police.

“In 99 percent of the cases, the family was relieved to have someone other than a police officer giving them that neutral assessment and help in understanding what is happening.”

Koehler says his family intervention program can help the police as well, by establishing a reliable bridge between the family and law enforcement that helps break down mistrust.

Seamus Hughes, deputy director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, says family intervention programs, like those developed by Koehler, can add an important dimension to counter-terrorism efforts.

“If you have upwards of 200 Americans who are trying to join groups like ISIS, just by sheer resource requirements you are going to have to figure out a different way besides arrest and takedown,” he says. “We just don’t have enough agents.”

He adds that, in some cases, prosecutors may lack sufficient evidence to file charges against someone or the target may be a minor. In those cases, it helps to have another option to address the potential danger.

“It is very hard for legal, moral, and policy reasons to arrest [someone] under age 18 for material support for terrorism,” Professor Hughes says. “So you are left with the only option of watching a 15-year-old kid radicalize to violence over a three-year period and then arrest him for material support [when he turns 18].”

“You know, FBI agents are parents, too,” Hughes says. “They don’t want to watch this train wreck happen in slow motion. So we have to provide some other avenue such as active interventions.”

Mom, dad, and civil liberties

There are also civil liberties considerations. Given the nature of Islamic extremism, there are frequently religious aspects and practices tied up in a potential investigation. Americans are rightly concerned when it appears that law enforcement and other government officials are acting in the capacity of the “thought police” or are seen to be infringing someone’s religious liberty or other constitutional rights.

Family interventions enjoy certain advantages in this respect, according to William Braniff, executive director of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland.

“The truth is, your mother and your soccer coach and your brother, they are not constrained by the Constitution,” Mr. Braniff says. “Your mother can violate your civil liberties all day long.”

Mothers hold an exalted place in Islam. “Paradise resides at the feet your mother,” the prophet Muhammad declared.

There is a clear mandate in Islam that a good Muslim honors his mother and father in all things, and must obtain the blessing of one’s parents before leaving for jihad.

This means that a mother is particularly well fortified to launch an intervention to save her son or daughter from a radical extremist group that purports to follow Islam.

“This is why many jihadist groups in the past have made it mandatory for their fighters to ask permission of the mother or father before they join the front lines or go on a suicide mission,” Koehler says.

“The Islamic State, of course, had to water that down because foreign fighters are so important for them,” he adds.

But Koehler notes that IS recruiters didn’t stop there. They use this parental approval process as part of their strategy to drive a wedge between parents and their children.

In the initial stages of radicalization, the target converts to a puritanical version of Salafi Islam, which they are told is the only true Islam. The recruiter then coaches the target to be especially kind to his parents and draw close to them emotionally, Koehler says.

“Then [the recruiter] would say the best form of honoring your parents is trying to convert them as well,” he says.

“So they try to convert the family, and in many cases this doesn’t work. So automatically there is a kind of frustration,” Koehler says.

“Then the [recruiter] would say, ‘All right, there, you see that the biological family is inferior to the spiritual family. We are all brothers and sisters in faith. All the family of believers is superior to your biological family.’ ”

In the next stage, he says, the recruiter plants a poison pill. “If your parents are not responding to that form of honoring them after giving them a chance to convert to the true faith, they are part of the enemy,” the recruiter suggests, according to Koehler. “This means if they are not with us, they are against us.”

Koehler spells out the recruiter’s logic: “And when you are against us, even your biological family, they are in a heartbeat as kuffar (unbelievers).”

What that means from the perspective of the Islamic State organization and its supporters is that the parents are now enemies of Allah and that it is no longer required to honor them, to seek their blessing, or even tolerate their existence.

Koehler says he has seen this scenario many times in his cases.

That is only part of what Koehler, Boudreau, and other interventionists are up against. But it illustrates that the recruiters recognize the critical need to break family bonds if they hope to successfully radicalize someone.

At the same time, this suggests that fortifying those same family bonds can effectively protect sons and daughters from extremism, experts say.

“Talk to your kids about subjects that are difficult,” says Dr. Erin Saltman of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue in London. “Young people are questioning a lot more than we give them credit for. Taking the time to have that conversation (about Syria and extremism), that helps work as a natural inoculation.”

Assessing the success of intervention programs is difficult. “Like a drug treatment program, you cannot actually prove that your intervention was the cause of the change in behavior,” Koehler says. But he notes that in the roughly 100 cases he’s personally worked on, “I would say in almost every case you could see that there was an immediate slowing down of the radicalization process.”

In addition, the target of the intervention isn’t the only one to benefit. Such programs provide invaluable help to mothers and other family members who would otherwise be struggling through the crisis alone.

Both Koehler and Boudreau say they are optimistic that a version of their family-based intervention program will soon be operating on a broader scale in the US.

It can’t come soon enough for Boudreau, whose Hayat Canada program does not receive any government funding in Canada and is currently running on a shoestring and her own dwindling checkbook, she says.

Despite growing financial challenges, Boudreau says she’ll find a way to respond to calls for help.

“We don’t turn anybody away,” she says. “We never turn anybody away.”

• Part 1, Monday: How doomsday Muslim cult is turning kids against parents

• Parts 2 & 3, Tuesday: One Virginia teen's journey from ISIS rock star to incarceration & Eight faces of ISIS in America

• Part 4, Wednesday: FBI tactics to unearth ISIS recruits: effective or entrapment?

• Part 5, Thursday: What draws women to ISIS

• Part 6, Friday: To turn tables on ISIS at home, start asking unsettling questions, expert says

• Part 7, Saturday: How to save kids from ISIS? Start with mom