How Chicago became ground zero for police reform this week

Loading...

| Chicago

In one corner of Chicago were 14,000 law enforcement leaders, lots of probing seminars, and President Obama. In another were 200 activists with signs and bullhorns.

Between them was a single question: What has changed since Ferguson?

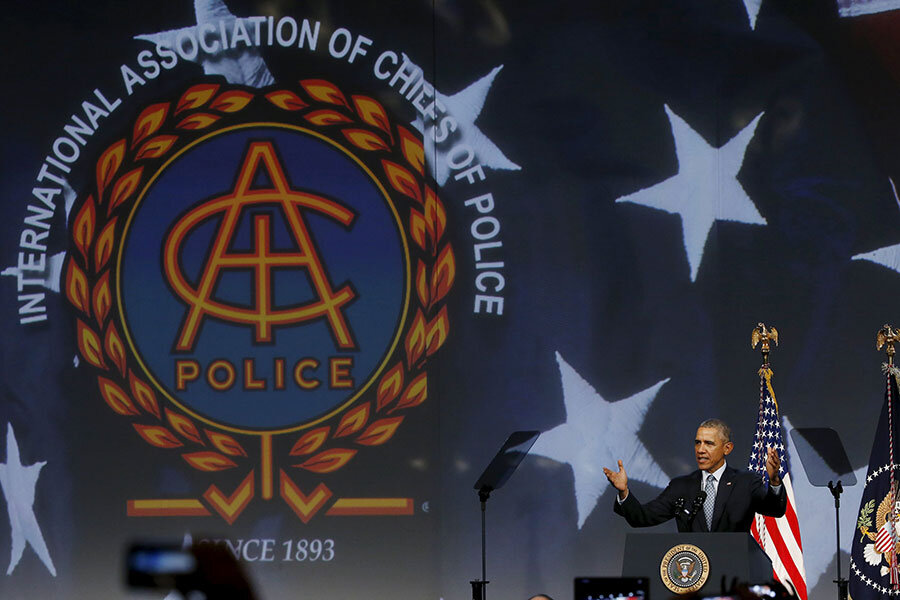

For the past four days, Chicago has been ground zero for the movement to reform policing. It was the scene of the annual International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) conference, which wrapped Tuesday with an address by Mr. Obama. But it was also the scene for the “I Shocked the Sheriff” counterconference, aimed at holding the police gathered in sprawling McCormick Place to account.

Their views of whether anything has improved since protests erupted in Ferguson, Mo., 14 months ago are radically different.

“We’re policing smarter, we’re policing better,” Chicago Police Supt. Garry McCarthy said at the IACP conference, echoing others there.

“I think [the police] may be more aware of the problems that are happening in police departments, but I don’t think there’s been any real change,” counters Camesha Jones of the Black Youth Project 100’s Chicago chapter, which led the protests.

The two conferences here have shown in real time the gulf that still lies between police and activists representing the black community. But both events, in their own ways, also have shown that the momentum for police reform is undiminished more than a year after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson.

The view from the police

“I’ve been doing this work for 30 years, and I’ve never seen such a spirit of openness and trying to figure out what’s appropriate for policing as I’ve seen here,” says Tom Tyler, a Yale University professor of law and psychology, who attended the IACP conference and spoke on a panel about improving community relations.

“If you had looked at most meetings of police leaders 10 years ago, they would have been dominated by discussions about how to control crime,” he adds. “After Ferguson, police commanders became aware that there was an additional issue that they needed to be aware about, which was how their actions were being viewed within the community.”

That change was apparent at the IACP conference. Law enforcement executives had their pick of a number of seminars on community relations. Other seminars focused on procedural justice, which emphasizes treating people with respect, ensuring fair processes, and building community trust.

The concept gained the support of the Department of Justice this year as a way to strengthen the relationship between law enforcement and the communities it serves. In March, former Attorney General Eric Holder announced six pilot sites for the Department of Justice’s $4.75 million National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice.

Professor Tyler says that procedural justice training programs have shown “dramatic declines in civilian complaints” about the police, and that they have been gaining traction in police departments across the United States. On the sidelines of the IACP conference Monday, another procedural justice program, called Train the Trainers, was launched with the support of the Chicago Police Department and researchers from Yale, John Jay College, and the University of California at Los Angeles.

The view from the protesters

For the activists at this week’s counterconference, however, changes in policing are coming far too slowly. While no national database of police shootings currently exists, a study by VICE News earlier this year found that 1,083 Americans were killed by police in the 12 months after Mr. Brown’s death

“We are not asking politely for the IACP to change their outlook on community policing,” Tanya Watkins – a leader of Southsiders Organized for Unity and Liberation, which helped organize the conference – told a crowd of protesters at the counterconference rally. “We are asserting our rights as Americans in this country to be governed in a way that does not kill us.”

After the rally on Saturday, Ms. Watkins and a couple hundred protesters marched to McCormick Place to give the IACP leadership a list of demands formulated during their counterconference. These included the decriminalization of the possession of drugs, the creation of a special prosecutor’s office in every police jurisdiction, and the reallocation of funds from law enforcement programs to community initiatives “that will end the prison pipeline and keep our communities safe.”

Activists blocked roads around McCormick Place for several hours, and one person climbed a flagpole at the convention center’s entrance and hung a Black Youth Project 100 flag over the American flag.

By the time the protest ended, 66 people had been arrested on misdemeanor charges for obstructing traffic.

“It’s one thing to say they’re going to make reforms and changes, but they’re not listening to the voices of young black organizers or people in the community who are being affected,” says Ms. Jones of the Black Youth Project 100. “We need people like me at the table.”

What has changed

Problems that existed in police departments before Ferguson are still largely there, says criminologist Samuel Walker, who has been studying policing for the past four decades. And it is too early to expect any significant changes in police behavior, he adds. Instead, the biggest difference in law enforcement today is protests like the one that took place Saturday.

“The whole conversation about policing has changed dramatically,” says Mr. Walker, an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska in Omaha. “The events of the last year or so have focused the attention on the police like never before.”

Walker says the country is in a crucial moment where policing has the potential to be transformed.

“We have a huge opportunity to make some real changes,” he says. “We have a lot of very good ideas that are out there. And the public understands these problems in a way that has not been true in the past.”

In his speech to the IACP Tuesday, Obama praised the police for reducing crime nationwide during the past two decades but said that there is still much work to be done to reduce officers’ bias and increase communities’ trust in the police.

“We’ve got to resist the false trap that says either there should be no accountability for police or that every police officer is a suspect no matter what they do,” he said. “Neither of those things can be right.”