Florida joins national trend to address backlog of rape kits

Loading...

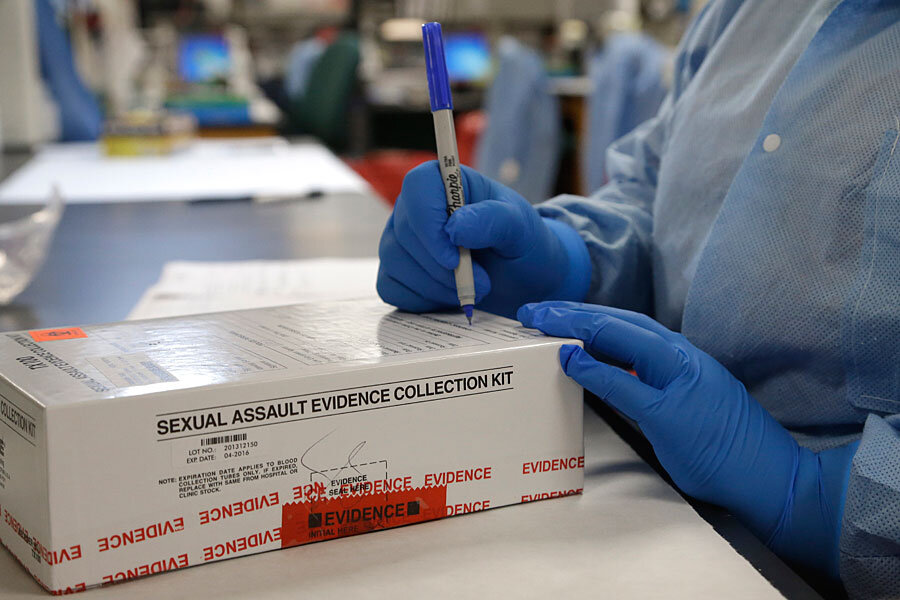

Florida's backlog of rape kits will finally be tested, thanks to a new law signed Wednesday by Florida Gov. Rick Scott (R).

Lawmakers and victim advocates hope the new legislation can alleviate the state's massive rape kit backlog and prevent similar backlogs in the future by mandating that all rape kits be submitted for processing within 30 days of a reported rape. After submission, they must be processed within 120 days.

Currently, Florida has a backlog of 13,435 rape kits, many of which have waited for testing for years, according to a Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) survey in January.

Florida joins a growing number of states that have taken steps to address this problem. Last summer, USA TODAY reporters found that nationwide, law enforcement offices held at least 70,000 unprocessed rape kits. Because they had surveyed only a small number of the nation’s law enforcement offices, the report estimated that hundreds of thousands of untested kits languished in storage facilities across the country.

Florida’s approach is part of a nationwide trend towards better rape kit testing practices, says Rebecca O'Connor, vice president of the Rape, Abuse, And Incest National Network's (RAINN), in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor. "It has been amazing to see a tidal wave of activity, both nationally and locally."

“What this legislation does is prevent Florida from having a backlog ever again,” said Jennifer Dritt, the executive director of the Florida Council Against Sexual Violence (FCASV), in a phone interview.

The legislation allocates $2.3 million to Florida labs so that they can deal with the existing backlog – part of a total of $10.7 million earmarked for forensic services, which includes updating lab equipment and providing training, among other uses. Ms. Dritt says that Florida has received federal grants to help process the kits.

"It will take us about three years to complete backlog testing at state labs, and that's with outsourcing the work, too," law enforcement spokeswoman Gretl Plessinger told the Florida Sun Sentinel.

Some of the backlog is due to law enforcement decisions, such as choosing not to pursue testing if a suspect has confessed. Some law enforcement officials attributed their lack of follow through to “lack of victim cooperation,” but Dritt says that accounts for only a tiny percentage of Florida’s backlog.

What does the new Florida law mean for rape survivors whose rape kits have sat untested for years?

“Some will be very relieved,” says Dritt. “There are other survivors who have moved out of state or who have given up hope and moved on.”

“Going forward,” Dritt told the Monitor, “I think survivors are by and large going to feel that their victimization is being taken seriously.”

Dritt notes that backlog testing could provide law enforcement with valuable clues. In other states where investigators have processed a backlog, Dritt says, links were found between seemingly unconnected cases.

“As a career prosecutor, I have seen first-hand the heartache caused by sexual assault,” said Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi in a press release, “and this legislation is a significant step toward bringing more predators to justice and helping victims heal.”

Rape kit backlogs have gained national attention over the last several decades.

Ms. O'Connor says that the problem became part of the national discourse in the early 2000s, after a rape survivor named Debbie Smith testified before Congress. Investigations by USA Today and CBS News also contributed to bringing the backlog to light.

With increased national attention has come new laws and more funding to process backlogs, says O'Connor. RAINN also supports the federal Sexual Assault Forensic Evidence Reporting Act (SAFER), which adds transparency to the problem and informs efforts to address the backlog through funding law enforcement audits of their untested sexual assault evidence kits and reporting requirements.

In 2014, California lawmakers required law enforcement to submit forensic evidence to a lab within 20 days of collection. Like Florida’s legislation, the California law is aimed at preventing backlogs.

A February Pew report on rape kit testing and legislation found that Michigan and Tennessee have also passed legislation that creates time limits for evidence submission.

According to Pew, other states, like Colorado, Illinois, Ohio, and Texas, have created backlog-reduction legislation, and others are considering doing so.

Dritt told the Monitor that legislation like Florida’s will “make our culture more informed in terms of believing survivors and taking them seriously.”

O'Connor echoed Dritt's words, adding that rape testing is a physically invasive process that can be difficult for victims. When states like Florida take steps towards streamlining the testing process, she says, "We are sending a clear signal to victims that they did it [the testing] for a reason, and that we are going to act on that evidence."

Moreover, O'Connor says, greater awareness has shifted the way law enforcement agencies view their own backlogs.

"What's really exciting is that we've gone from a place where a number of jurisdictions were defensive about this problem," says O'Connor. "It's an issue that isn't restricted to one jurisdiction, and it is great to see a shift in tone, where law enforcement agencies work together with national agencies to deal with the problem."