Why did sex assault 'Survivors' Bill of Rights' earn bipartisan backing?

A bill that passed both the US House and Senate without opposition became law Friday, when President Obama signed the measure, guaranteeing certain rights for victims of sexual assault in federal criminal cases.

The legislation, known as the Survivors' Bill of Rights Act, guarantees that victims will not have to pay for a rape kit to collect physical evidence in the event of a suspected sexual assault, and it expressly permits survivors to request that their kits be preserved until the statute of limitations expires.

Most sexual assault cases are tried in state courts, not at the federal level, but the new law could serve as a model for state legislatures, perhaps ushering in a nationwide discussion on how to refine the criminal justice system's handling of rape cases. Seven states are already considering similar bills, as The Christian Science Monitor's Stacy Teicher Khadaroo reported.

Amanda Nguyen, who helped draft the proposal that became the basis for the congressional and Massachusetts bills, told the Monitor last spring that her activism began at a hospital in 2013:

Within 24 hours of being sexually assaulted, she underwent the hours-long examination to collect evidence for a rape kit. One of the pamphlets she received told her that if she didn’t report the crime to law enforcement, the kit would be destroyed in six months – unless she filed for an extension. In Massachusetts, the statute of limitations for the prosecution of rape is 15 years.

There were no directions about how to get the extension, and Ms. Nguyen decided she wasn’t ready to go through the often grueling process of pursuing criminal charges for rape. She also wasn’t ready to have the evidence of the crime committed against her summarily tossed. So she entered what she describes as a “labyrinth” to figure out how to preserve the kit.

“Every six months, my life is reoriented to the date of the rape, because I have to fight to hold on to my kit [so it’s not] destroyed in the trash can,” she says in a phone interview.

In an interview with NPR, Ms. Nguyen explained that the law she pushed lawmakers to pass includes straightforward provisions.

"It includes really non-controversial basic things like the right to have your evidence not be destroyed before the statute of limitations, access to medical results from the rape kit or forensic examination and the right to receive a copy of your own police report, the right to be notified of what your rights are in that state because your rights can vary from state to state," Nguyen said.

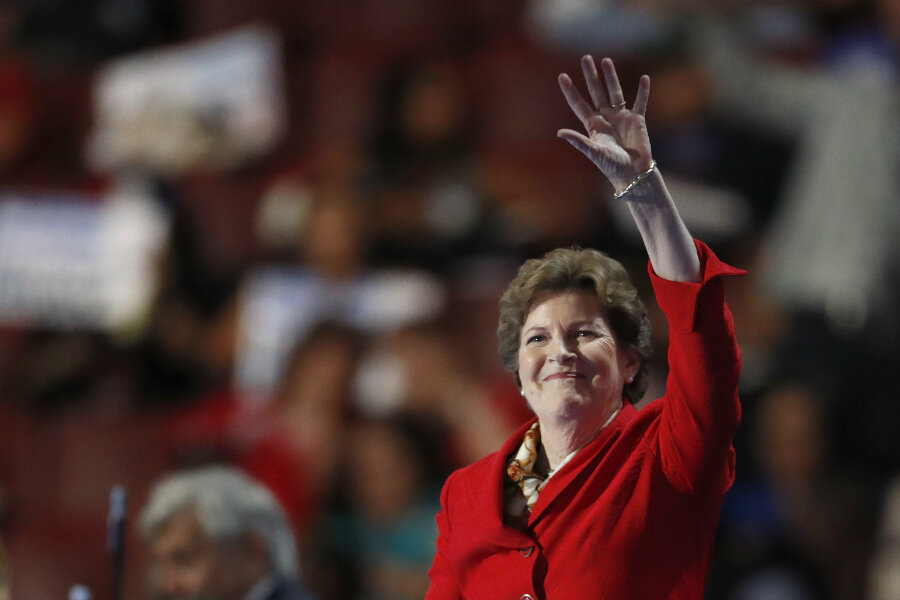

US Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, a Democrat from New Hampshire who backed the bill, released a statement Friday thanking Nguyen by name.

"Amidst the partisan bickering and gridlock in Congress, this law demonstrates that citizens can still effect positive change and that bipartisan progress is still possible," Senator Shaheen said, noting that sexual assault is still one of the most underreported crimes in the United States.

For every 1,000 rapes committed, only about 344 are reported to police, leading to 63 arrests, 13 referrals for prosecution, just seven felony convictions, and six rapists in prison, according to estimates by the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), as the Monitor reported earlier this year. By comparison, an estimated 20 robbers are serving time for every 1,000 robberies committed.

US Rep. Mimi Walters, a Republican from California who introduced the bill in the House, said in a statement Friday that the measure is an important first step.

"There is an uneven patchwork of laws across this country that prevents sexual assault survivors from having full access to the justice system," Representative Walters said. "This law guarantees these rights in the federal criminal justice system, but it is my hope this law will set an example for states to adopt similar procedures and practices."

Scott Berkowitz, founder and CEO of RAINN, said Americans are waking up to the need to better respond to sexual violence, but the problem persists.

"There’s been a gradual improvement in understanding that we can’t give people a pass because they are famous or popular," he said, "but I don’t think that problem has gone away yet."