Forced to work? 60,000 undocumented immigrants may sue detention center

Loading...

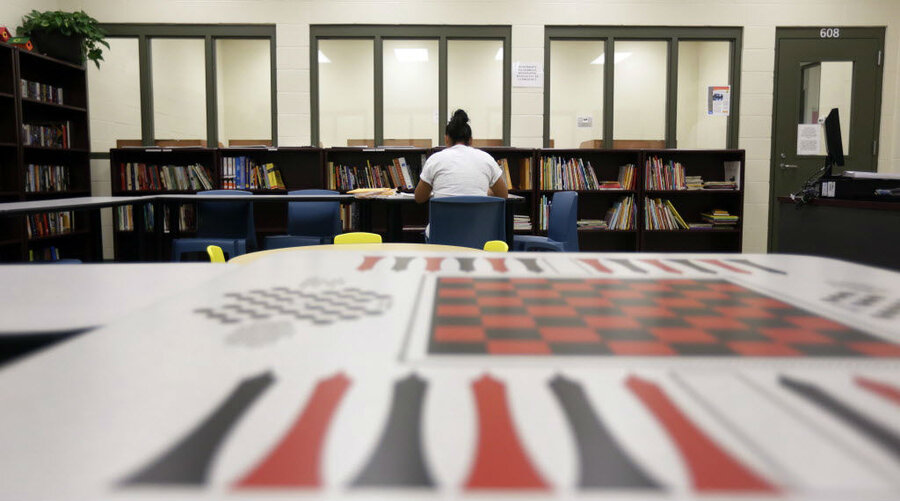

A class action suit alleging that as many as tens of thousands of undocumented immigrants were coerced to perform free labor in a privately operated Colorado detention center has been given the green light to move forward in a federal district court.

On Tuesday, a district judge ruled to grant the 2014 lawsuit class action certification, marking the first time a class action suit alleging forced labor has been brought against a private prison. The suit was launched by nine former and current detainees at the Aurora Detention Facility, a holding center near Denver, Colo., operated privately on behalf of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The lawsuit may now encompass as many as 60,000 people detained at the center between 2004 and 2014, according to Andrew Free, one of the plaintiff’s attorneys.

Roughly 34,000 people are in immigration detention centers on any given day in the United States, 60 percent of whom in privately operated facilities. Running those centers proves a pricey task, and private prison operators – which stand to gain by employing cheap labor to maintain the centers and turn a profit – resort to legal, cheap labor on part of detainees.

But the first-of-its-kind case could shed further light on an ongoing issue. As more argue that detainees and prisoners must be paid – and at wages higher than $1 per day – a shakeup of the system could take place.

While low-wage work has long been a feature of the United States prison system, there’s a legal difference between forcing those who have committed a crime and therefore foregone some 13th Amendment protections to earn their stay in prison, and those being held on civil matters, like immigrants. Coercing detainees to perform labor would violate ICE work standards, which guarantee the protection from workplace hazards as well as discrimination in voluntary programs.

“Residents will be able to volunteer for work assignments, but otherwise not be required to work, except to do personal housekeeping,” the agency’s standards state.

“The private prison immigration detention center and ICE collaboration doesn’t really work without the forced labor of these detainees in Aurora,” plaintiff's attorney Mr. Free told The Christian Science Monitor.

“The question is, if the business model relies on having detained people clean, cook, do laundry, cut hair, maintain the facility – that’s what the business model requires in this particular case – are we able to shift that business model? Is the American taxpayer comfortable footing that bill?”

While novel in its scope, the suit also comes at a time when immigration policy is slated to shift under President Trump’s administration. Immigration officials have increased enforcement activity, the administration plans to expand its number of detention facilities, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions made clear that much of the prison system will remain privately operated.

The suit “sheds light on the way in which the detention system operates,” Carl Takei, a staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties National Prison Project, tells the Monitor in a phone interview.

“We have a name for the practice of locking people up and forcing them to work without paying them real wages," he adds. "It’s called slavery. And companies like GEO group stand to profit immensely from the expansion of detention centers that the Trump administration has laid out in its executive orders.”

The suit alleges that GEO, the private-prison giant operating the Aurora facility, violated the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, a measure passed in 2000 with the intention of shielding undocumented immigrants who are victims of trafficking and violence, as well as forced labor. The plaintiffs contend that they were forced to work “without any compensation and under the threat of solitary confinement.” The suit also notes that when paid $1 per day, detainees made much less than Colorado’s minimum wage of $9.30 per hour.

GEO moved to dismiss the case. While a judge threw out the piece of the case involving a call for minimum wage earnings in prisons, he allowed the segment involving coerced labor to stand.

The company has denied allegations that it threatened inmates with solitary confinement in order to obtain free labor.

“We have consistently, strongly refuted these allegations, and we intend to continue to vigorously defend our company against these claims,” Pablo Paez, a GEO spokesman, said in a statement to the Monitor. “The volunteer work program at immigration facilities as well as the wage rates and standards associated with the program are set by the Federal government. Our facilities, including the Aurora, Colo., facility, are highly rated and provide high-quality services in safe, secure, and humane residential environments pursuant to the federal government’s national standards.”

Whether at the Aurora facility or elsewhere around the country, experts say coercion plays a large role in getting detainees to work, but uncovering it can prove a nearly impossible task.

“You can’t underestimate the level of coercion involved,” Mr. Takei says of detention centers and prisons around the nation. “If you refuse to work as a detainee, you can be thrown in solitary confinement. There is no parallel to that in the free world. If I were to call my boss tomorrow morning and say I’m not showing up to work, he might be able to fire me, but he couldn’t throw me in a cell the size of a parking spot.”

Whether inmates were coerced at the Aurora facility remains to be proven in court proceedings, but concerns linger for those who choose to work and only bring home between $1 and $3 a day.

“It was voluntary,” Delmi Cruz, a detainee at a GEO-run facility in Texas, previously told the Los Angeles Times of her stint cleaning bathrooms and hallways where she made $3 a day. “[But] it wasn't fair."

While some cite the benefits behind the programs, such as putting extra cash in detainees’ commissary accounts or teaching them a new skill, many argue that ICE-mandated earnings should increase, or that private companies should pay a higher rate.

That debate has brewed around both prisons and detention centers. And as Mr. Trump pivots away from Obama-era policies regarding private ownership, calls for better wages for detained and incarcerated works will only grow louder.

“The spotlight has certainly been on private corporations running and managing prisons. It certainly was last year under the Obama administration, and the momentum has changed under Trump,” says Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior counsel for the Justice Program at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York.

“Paying $1 to $3 a day is incredibly low," she says. "Just like in a state prison, if someone wants to participate in a work program, they should be compensated at a higher wage.”