Are racial gaps in US justice system inevitable? New data shows progress.

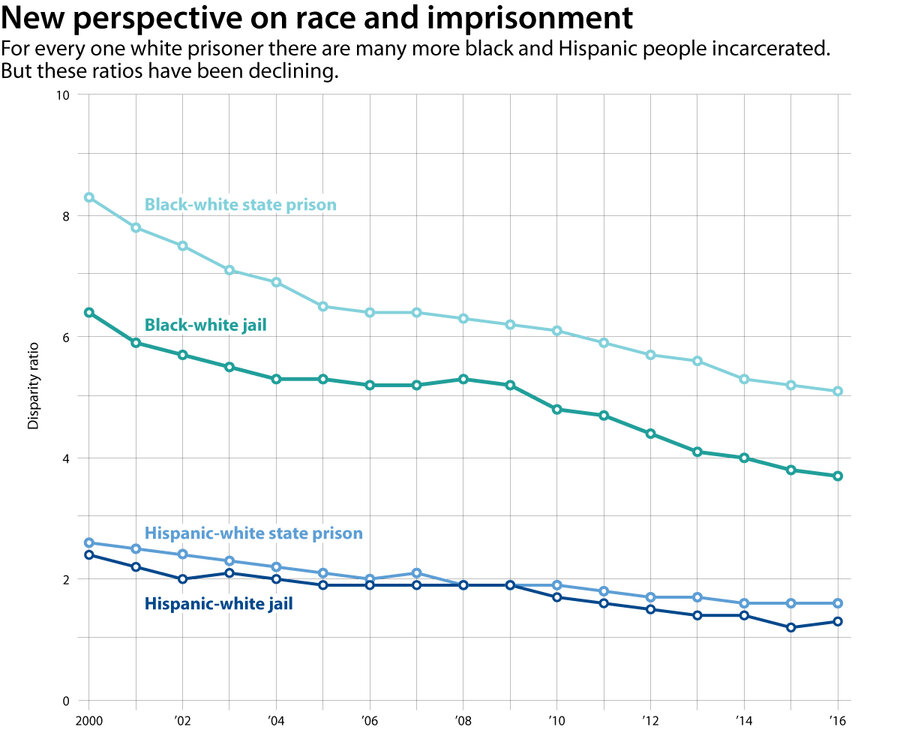

It’s come as a surprise to many: Racial disparities in the criminal justice system have declined dramatically since the start of the millennium.

At times, the disparities have seemed like an intractable problem, tied to issues ranging from uneven drug sentencing laws and implicit bias to poverty and crime trends. But now, the Council on Criminal Justice in Atlanta has presented new evidence of a shift. It found a narrowing of the large gaps between the incarceration rates for white people and those for black and Hispanic people. The same went for gaps in jails, probation, and parole.

In 2016, for instance, the black-white ratio in state prisons was 5.1-to-1, down from 8.3-to-1 in 2000.

Council on Criminal Justice

Why We Wrote This

Reducing racial disparities, such as those seen in incarceration rates, has long been a priority for justice reform advocates. Here are several depictions showing dramatic advances at the state level.

“We were aware of the direction of the change but didn’t really have any sense of the magnitude,” says Adam Gelb, the council's CEO and president. “This is a situation that’s gone from worse to bad. If we’re serious about shrinking these gaps further, we’ve got to have a deeper understanding of what lies behind these trends.”

The state imprisonment gaps declined across all types of crimes, but most sharply with drug offenses. The 15-to-1 black-white divide dropped to below 5-to-1 for drug-related imprisonment.

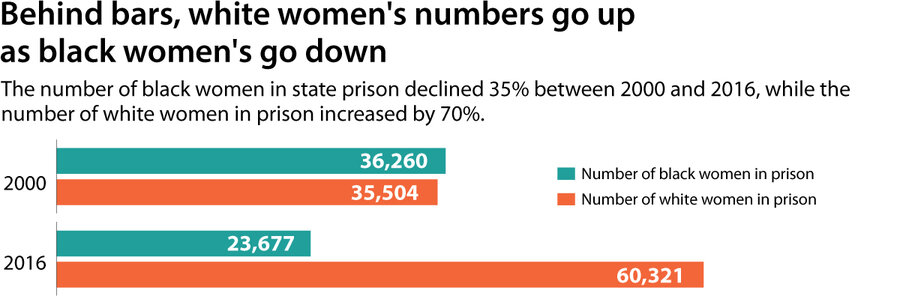

The trend is particularly notable among women. The black-white ratio for women in state prison dropped from 6-to-1 in 2000 to 2-to-1 in 2016.

That translates to over 12,000 fewer black women in prison, with the reductions happening mostly in the category of drug offenses.

But reductions for black women have been happening alongside an increase in white women serving time. Advocates say they’d prefer to see gaps closing in the context of a reduction in crime and imprisonment among all racial categories.

One hypothesis for some of the decline in drug-imprisonment disparities, says Mr. Gelb, is that prior to the age of smartphone and internet ubiquity, urban drug crimes tended to be out on the street corner, prompting neighbors to call the police and contributing to more arrests of black and Hispanic residents.

There are still strong concerns about underlying injustices factoring in to people of color being arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned at higher rates than white people, says Nazgol Ghandnoosh, a senior research analyst at The Sentencing Project in Washington, D.C.

“If those disparities are unwarranted and they don’t stem from differences in crime rates ... communities of color will feel that they’re being discriminated against by the justice system and be less likely to cooperate,” she says.

A number of reforms could be contributing to leveling imprisonment rates.

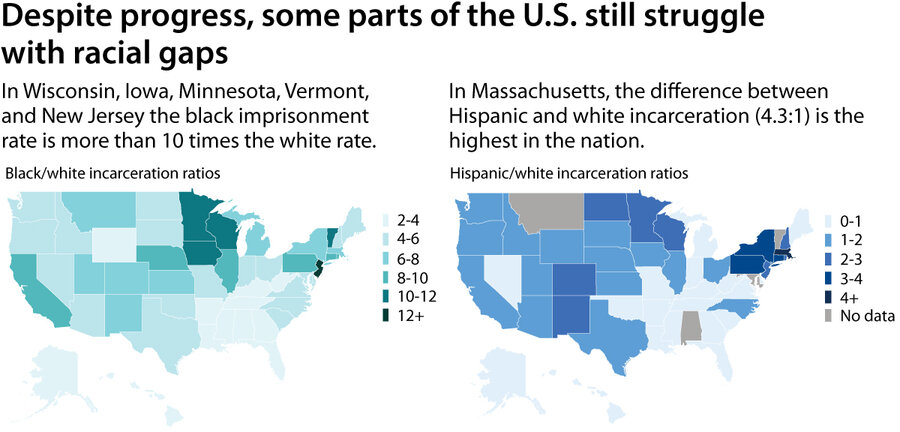

Changes in drug-free school zone sentencing laws are one example. Because more residents of color go about their daily lives in dense neighborhoods within the wide radius of a neighborhood school, some cities and states have begun to narrow those zones or give judges more discretion over sentencing. New Jersey modified its law in 2010, for instance, and judges in the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester have worked with prosecutors to reduce disparities involving school-zone sentencing, The Sentencing Project reports.

States such as New Jersey, Connecticut, and Iowa have required that before a criminal justice law is passed, an analysis must be done on any potential for disparate racial impact.

Critics say the focus on racial gaps is misplaced. “The premise of an enterprise like racial impact statements is that any disparity in the criminal justice system, with regard to the end results of incarceration rates, grows out of some sort of hidden racial bias. In fact, the disparities in the criminal justice system grow out of disparities in behavior,” says Heather Mac Donald, author of “The War on Cops” and a fellow at the Manhattan Institute. “When you try to mold policies to avoid racial disparities, you are going to be twisting them to avoid penalizing criminal behavior – and [those] victimized by that are going to be law-abiding residents in minority communities.”

Within the overall decline, states’ racial disparities vary significantly.

Racial gaps in federal prisons have also declined, though not as dramatically. That’s partly due to the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which adjusted an imbalance in prison terms for possession of crack or powder cocaine. Further reductions could be on the way because prisoners can now apply to make adjustments for sentences given before 2010 – an opportunity embedded in the bipartisan First Step Act passed by Congress in 2018.

“Ideally in our society,” says Ms. Ghandnoosh, “we would have equality in opportunities and equality in outcomes so that we don’t see differences in criminal offending, and so that we don’t have to think that if you’re white or not, if you’re rich or not, you will have a very different likelihood of contacting the justice system.”