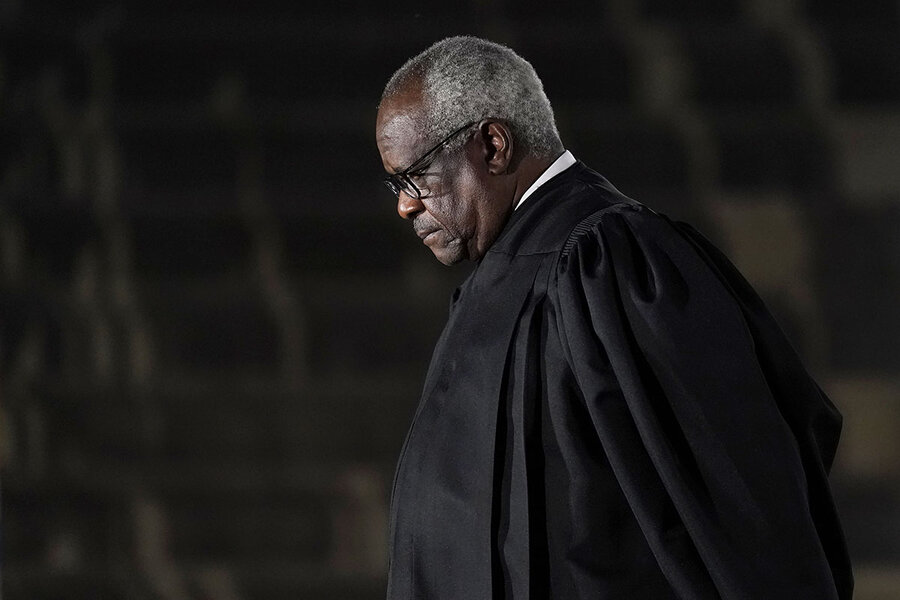

To understand this Supreme Court, watch Clarence Thomas

It was a slip of the tongue, but an illustrative one. During an oral argument in March, a lawyer referred to United States Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as “Mr. Chief Justice.”

“Thank you for the promotion,” Justice Thomas replied, his booming laugh momentarily filling the live-broadcast argument.

There’s no chance of a coup in the nation’s highest court. But it’s fair to say that Justice Thomas – a sometimes idiosyncratic stalwart of conservative jurisprudence – has never been more of a keystone for the court than he is now.

For the term that concluded last week, that meant a surprising amount of unanimity, and some unusual alignments in some high-profile cases. On the surface, at least, it was a relatively quiet term. But next term, with some blockbuster cases on abortion and gun rights already on the docket, could see the “Thomas court” take on a very different meaning.

“It’s a court in flux” at the moment, says Ilya Shapiro, a vice president of the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. And Justice Thomas, he adds, “is definitely at the height of his influence.”

The term’s unexpected twists

In some respects, the Supreme Court defied expectations last term. Justice Amy Coney Barrett arrived a month into the session, replacing liberal icon Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died five weeks earlier, and cementing a 6-3 conservative supermajority on the court. But the predicted flurry of conservative-friendly rulings hasn’t been realized.

The court upheld the Affordable Care Act, for a third time, in a 7-2 ruling. That same day, in a high-profile religious liberty case, it issued a unanimous but narrow ruling in favor of a Catholic foster agency. Of the 16 rulings the court made 6-3 last term, there were five different alignments. Justice Thomas twice voted with the court’s three liberals in divided cases.

This is still a very conservative Supreme Court, however, as evidenced by two opinions on the final day of the term. Both 6-3 rulings were along ideological lines – one significantly reined in a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, and the other represented something of a personal victory for Justice Thomas.

In the latter case, the court struck down as unconstitutional a California law requiring charities to disclose the identities of their major donors to the state. Justice Thomas has criticized such laws for years, saying they violate donors’ right to freedom of association.

“Now six justices really buy into that concept,” said Sarah Harris, a partner at the law firm Williams & Connolly and a former clerk for Justice Thomas, at a webinar last week hosted by the American Constitution Society.

“That’s a big change in the law throughout the last 20 years,” she added.

These kinds of wins are sprinkled through Justice Thomas’ three decades on the court. Two of the biggest Supreme Court wins for conservatives this century – expanding gun rights in Heller v. District of Columbia, and reversing campaign finance restrictions in Citizens United v. FEC – came years after he had made similar arguments in solo concurrences.

Those cases are the exceptions, however – at least to date. Some of his arguments, such as one (made on several occasions) that the Constitution’s ban on government establishment of religion doesn’t apply to the states, are unlikely to gain traction with a majority of the court. But after decades of writing alone from the conservative fringe, he seems to have more power and more support.

“Several [justices] are closer to Thomas” ideologically than other conservatives on the court, says Mr. Shapiro. “He has more allies.”

Typically the court’s most prolific author, Justice Thomas led the way again last term with 23 opinions. But at least one colleague joined him in all but seven – his lowest number of solo opinions since the 2013-14 term.

Chief among those allies is Justice Neil Gorsuch, the colleague he agreed with most. Among the cases where they staked out similar positions was a First Amendment case the court declined to hear. In separate dissents, both justices argued that New York Times v. Sullivan – the 1964 precedent protecting the right of journalists and the public to criticize public officials – should be revisited.

On the ideological flip side, he voted to uphold the Affordable Care Act. And two administrative law cases also saw Justice Thomas write dissents joined by the court’s progressive wing. Together it illustrates that, while Justice Thomas may have more influence now than ever before, he’s still, well, Justice Thomas.

“He’s a solidly politically conservative justice,” says Steven Schwinn, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law. But “he has an independent streak.”

How wide that independent streak stretches next term, with a slate of hot-button cases already on the docket, is a major question.

How conservative is the court?

Because the Supreme Court is now so conservative, the justices are being asked to hear more cases seeking to push the law in a rightward direction. Those cases have divided the court’s conservative wing, however, on the question of how quickly and broadly the law should change.

Last term, the court mostly trod a narrow path, adopting limited rulings and avoiding the cases’ bigger questions.

Next term “the court [may] start defining itself more,” says Mr. Shapiro of the Cato Institute. But with moderate conservatives like Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh at its ideological center, he adds, “it’s still a cautious and incrementalist court.”

Other experts believe the Roberts court is, and has long been, only selectively incrementalist. While the court issued some narrow rulings in big cases last term, they note, it also crafted significant changes to voting rights law on the final day of the term.

“It’s not like the court is always passive or always active. It’s ever-varying activity or restraint,” says Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a professor at Harvard Law School.

“It’s not a total surprise that a conservative court sometimes feels uneasy with the most conservative arguments put in front of it,” he adds. But “on the right kinds of cases there’s no question this is an ultraconservative, ultra-ideological court.”

Next term the court has already agreed to hear several of what could be those “right kinds” of cases for the conservative justices. Abortion, gun rights, and state funding for religious schools are all on the docket. The justices are also still considering taking up a case on affirmative action at Harvard University. (Last month they asked the Biden administration to weigh in on the case.)

These are also cases that could see the court move the law closer to how Justice Thomas views it. Earlier this year a solo concurrence he wrote in 2019 associating abortion with eugenics began to gain traction in lower federal courts. He has long been a critic of affirmative action.

The last time the court decided an affirmative action case it was months after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. The justices upheld a University of Texas race-based admissions policy in a deadlocked ruling, and Justice Thomas wrote a fiery dissent.

It was in that moment, with the court’s ideological balance poised to flip from conservative to liberal for the first time in decades, that the court’s most conservative justice looked “destined to serve out his term at the even more distant fringe,” wrote The New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin.

Five years and four new justices later, and with a blockbuster term months away, Justice Thomas has never looked closer to the court’s mainstream.