Why Supreme Court seems likely to sink Biden’s loan forgiveness plan

Loading...

| Washington

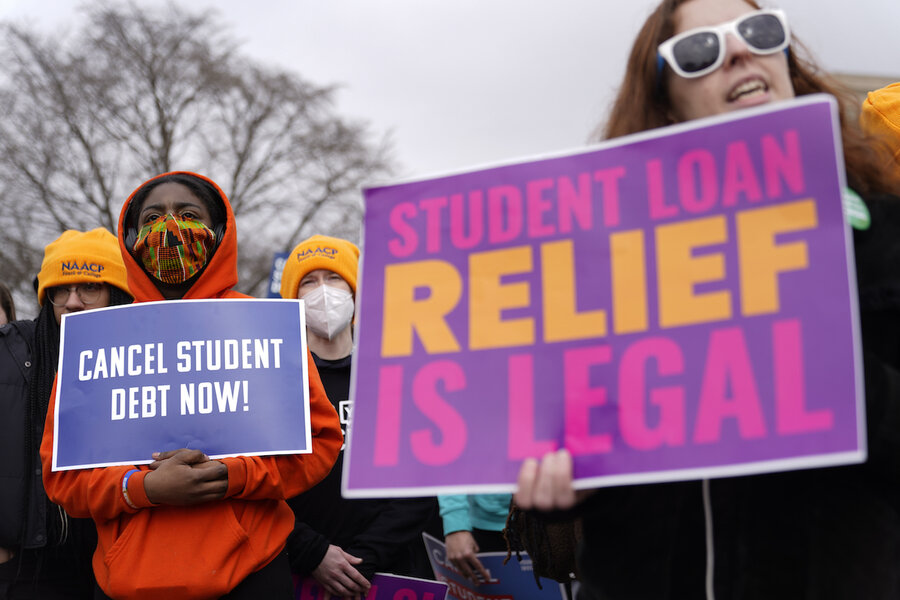

Conservative justices holding the Supreme Court’s majority seem ready to sink President Joe Biden’s plan to wipe away or reduce student loans held by millions of Americans.

In arguments lasting more than three hours Tuesday, Chief Justice John Roberts led his conservative colleagues in questioning the administration’s authority to broadly cancel federal student loans because of the COVID-19 emergency.

Loan payments that have been on hold since the start of the coronavirus pandemic three years ago are supposed to resume no later than this summer. Without the loan relief promised by Mr. Biden's plan, the administration’s top Supreme Court lawyer said, “delinquencies and defaults will surge.”

The plan has so far been blocked by Republican-appointed judges on lower courts. It did not appear to fare any better with the six justices appointed by Republican presidents.

Mr. Biden’s only hope for being allowed to move forward appeared to be the slim possibility, based on the arguments, that the court would find that Republican-led states and individuals challenging the plan lacked the legal right to sue.

That would allow the court to dismiss the lawsuits at a threshold stage, without ruling on the basic idea of the loan forgiveness program that appeared to trouble the justices on the court’s right side.

Mr. Roberts was among the justices who grilled Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar and suggested that the administration had exceeded its authority.

Three times, the chief justice said the program would cost a half-trillion dollars, pointing to its wide impact and hefty expense as reasons the administration should have gotten explicit approval from Congress. The program, which the administration says is grounded in a 2003 law that was enacted in response to the military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, is estimated to cost $400 billion over 30 years.

“If you’re talking about this in the abstract, I think most casual observers would say if you’re going to give up that much ... money, if you’re going to affect the obligations of that many Americans on a subject that’s of great controversy, they would think that’s something for Congress to act on,” Mr. Roberts said.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh suggested he agreed, saying it “seems problematic” for the administration to use an “old law” to unilaterally implement a debt relief program that Congress had declined to adopt.

Neither justice seemed swayed by Ms. Prelogar’s explanation that the administration was citing the national emergency created by the pandemic as authority for the debt relief program under a law commonly known as the HEROES Act.

“Some of the biggest mistakes in the court’s history were deferring to assertions of executive emergency power,” Mr. Kavanaugh said. “Some of the finest moments in the court’s history were pushing back against presidential assertions of emergency power.”

At another point, though, Mr. Kavanaugh suggested the program might be on firmer legal ground than other pandemic-related programs that were ended by the court’s conservative majority, including an eviction moratorium and a requirement for vaccines or frequent testing in large workplaces.

Those earlier programs halted by the court were billed largely as public health measures intended to slow the spread of COVID-19. The loan forgiveness plan, by contrast, is aimed at countering the economic effects of the pandemic.

Ms. Prelogar and some of the liberal justices sought several times to turn the arguments back to the people who would benefit from the program. The administration says that 26 million people have applied to have up to $20,000 in federal student loans forgiven under the plan.

“The states ask this court to deny this vital relief to millions of Americans,” she said.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor said her fellow justices will be making a mistake if they take for themselves, instead of leaving it to education experts, “the right to decide how much aid to give” people who will struggle if the program is struck down.

“Their financial situation will be even worse because once you default, the hardship on you is exponentially greater. You can’t get credit. You’re going to pay higher prices for things,” Ms. Sotomayor said.

But Mr. Roberts pointed to evident favoritism.

He offered a hypothetical example of a person who passes up college to start a lawn service with borrowed money. “Nobody’s telling the person who is trying to set up the lawn service business that he doesn’t have to pay his loan,” Mr. Roberts said.

Republican-led states and lawmakers in Congress, as well as conservative legal interests, are lined up against the plan as a violation of Mr. Biden’s executive authority. Democratic-led states and liberal interest groups are backing the administration in urging the court to allow the plan to take effect.

The justices’ questions mirrored the partisan political divide over the issue, with conservatives arguing that non-college workers should not be penalized and liberals arguing for the break for the college-educated.

Speaking on the eve of the arguments, Mr. Biden had said, “I’m confident the legal authority to carry that plan is there.”

The president, who once doubted his own authority to broadly cancel student debt, first announced the program in August. Legal challenges quickly followed.

The administration says the HEROES Act allows the secretary of education to waive or modify the terms of federal student loans in connection with a national emergency. The law was primarily intended to keep service members from being hurt financially while they fought in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Nebraska and other states that sued say the 20 million borrowers who would have their entire loans erased would get a “windfall” leaving them better off than before the pandemic.

“This is the creation of a brand new program, far beyond what Congress intended,” Nebraska Solicitor General James Campbell said in court Tuesday.

The national emergency is expected to end on May 11, but the administration says the economic consequences will persist, despite historically low unemployment and other signs of economic strength.

In addition to the debate over the authority to forgive student debt, the court is confronting whether the states and two individuals whose challenge also is before the justices have the legal right, or standing, to sue.

Parties generally have to show that they would suffer financial harm in order to have standing in cases such as this. A federal judge initially found that the states would not be harmed and dismissed their lawsuit before an appellate panel said the case could proceed.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the three liberal justices in repeatedly questioning Nebraska’s Campbell on that issue. But it would take at least one other conservative vote to form a majority.

Of the two individuals who sued in Texas, one has student loans that are commercially held, and the other is eligible for $10,000 in debt relief, not the $20,000 maximum. They will get nothing if they win their case.

Among those in the courtroom Tuesday was Kayla Smith, a recent graduate of the University of Georgia, who camped out near the court the night before in order to get a seat. Mr. Biden’s plan would lift a burden for her mother, who borrowed more than $20,000 in federal student loans to help Ms. Smith attend college.

“It just seems kind of messed up that college is the expectation, higher education is the expectation, but then at the same time, people’s lives are being ruined,” said Ms. Smith, 22, who lives in Atlanta.

The arguments are available on the AP YouTube channel or on the court’s website.

A decision is expected by late June.

This story was reported by The Associated Press. AP writer Collin Binkley contributed to this report.