Can Trump run? Historic case will test Supreme Court.

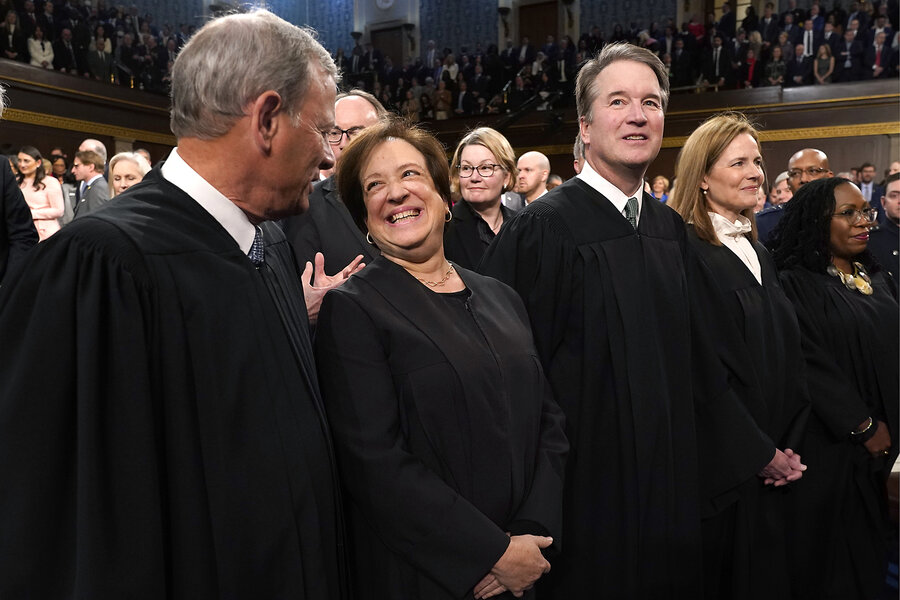

When they don their black robes and enter the U.S. Supreme Court chamber tomorrow, the nine justices of the court will be stepping into unfamiliar territory.

For the first time in its history, the Supreme Court is being asked to determine if the Constitution disqualifies a presidential candidate. Specifically, Thursday’s case asks if a Civil War-era constitutional provision bars Donald Trump from the ballot because of his actions on and around the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The case, Trump v. Anderson, echoes several of the high court’s most momentous decisions. The lawsuit raises novel and complex legal questions, it concerns a pressing and divisive national issue, and it will have immediate and profound consequences for the country. Whatever decision the Supreme Court reaches, it will anger a significant portion of the electorate.

Why We Wrote This

The Supreme Court issues landmark decisions every term. But they normally don’t involve obscure sections of the Constitution, a presidential election, and a need for speed. Trump v. Anderson is going to test the justices’ ability to work as a court.

The current high court is no stranger to consequential rulings. In the past two years alone, the court has issued landmark decisions in cases involving abortion access, gun rights, and affirmative action.

While those issues have been heavily litigated for decades, the justices will go into Thursday’s argument with very little experience adjudicating this section of the Constitution. It will also be the first time they hear a case pertaining directly to the deadly Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol riot and the aftermath of Mr. Trump’s persistent false claims that the 2020 presidential election was stolen.

“Most of the time, the justices know what they think about a particular case, and they have a pretty good idea of what the others think” before oral arguments, says Gerard Magliocca, a professor at Indiana University School of Law.

“This time, neither will be true,” he adds. “They’re all going to be going in there looking for what the others think, and that, in turn, will influence what they think, much more so than in a normal argument.”

What does Section 3 say?

Last month, the Colorado Supreme Court held that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment prohibits Mr. Trump from appearing on the state’s primary ballot. The 19th-century provision, ratified as ex-Confederates were seeking a return to government after the Civil War, prohibits anyone who “engages in insurrection” against the United States from holding public office. Congress can remove this disqualification with a two-thirds vote, per Section 3, and did so for Civil War veterans in a few cases.

The provision has been used sparingly since the 1870s, but the Jan. 6 attack and Mr. Trump’s 2024 campaign have brought Section 3 out of obscurity. Since last summer, legal groups and voter coalitions have been filing lawsuits in at least a half-dozen states, claiming that Section 3 disqualifies Mr. Trump. Most of these suits haven’t succeeded, but in late December the Colorado Supreme Court ruled 4-3 that he is ineligible to run in the state’s primary.

The scarcity of Section 3 cases over the centuries “tells you there haven’t been many instances of an insurrection against the United States,” says Manisha Sinha, a professor of American history at the University of Connecticut who joined a historians’ amicus brief arguing that Mr. Trump is disqualified.

Nevertheless, the 14th Amendment “is the foundation of modern democracy in the United States,” she adds. While Section 3 may be infrequently used, “it’s not something we can pick and choose to obey or to implement.”

It’s also not something to be done lightly, according to Will Baude, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School. He helped spark the national debate over Section 3 last summer when he co-authored an in-depth law review article arguing that Section 3 disqualifies Mr. Trump.

“Disqualifying people from the ballot is a big deal,” said Professor Baude this week on a University of Chicago’s “Big Brains” podcast.

“In a healthy democracy, you don’t need these kinds of disqualification provisions,” he added. “Unfortunately, Section 3 was enacted out of fear that we didn’t always have a perfectly healthy democracy.”

For his part, Mr. Trump argues that American democracy is healthy – but is threatened by this case. On the other side, critics say nothing could be less democratic than allowing someone who incited his supporters to violently stop Congress certifying his electoral defeat to hold the most powerful office in the country.

Mr. Trump’s lawyers opened a recent brief by citing his margins of victory in the 2024 Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary. “The American people – not courts or election officials – should choose the next President of the United States,” they added.

In an amicus brief, 179 members of Congress argue that the Colorado Supreme Court decision “provides a green light for partisan state officials to disqualify their opponents” in the future and “interfere with the ordinary democratic process.”

But “democracy” is almost besides the point in a Section 3 case, or in any constitutional law case, experts say. The Founding Fathers feared both a monarch and mob rule. This is precisely why the highest law of the land is not how a majority votes but what the Constitution says. The Supreme Court will have to determine if this section of the Constitution applies in this case.

“The Constitution restricts us to a particular implementation of democracy,” says Vikram Amar, a professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law. “The $64,000 question is what the Constitution means one way or the other.”

Can the court act as one?

Thus, the oral argument is likely to focus on a set of rarely litigated constitutional questions. Is Section 3 “self-executing”? Does the clause even apply to the presidency? Do Mr. Trump’s actions on and around Jan. 6 constitute “engaging in insurrection”?

Legal scholars disagree on all those questions. Given the gravity of the case, however, scholars on both sides agree that the Supreme Court needs to reach a decision – meaning a definitive answer on whether Mr. Trump is disqualified by Section 3 – on the merits as soon as possible.

As unanimously as possible would be helpful as well.

The Supreme Court does have a tradition of deciding these rare, momentous cases unanimously. Perhaps most famously, the court banned racial segregation in public schools with a unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Two decades later, a unanimous court ordered that Richard Nixon had to hand over materials related to the Watergate investigation, precipitating his resignation.

At the other end of the spectrum would be Bush v. Gore, which divided the court along ideological lines. In a case that effectively decided the 2000 election in favor of George W. Bush, the high court – in a per curiam order issued the day after oral argument – halted a recount in Florida.

The justices “will really want to work hard to try to find as much consensus as possible,” says Professor Amar.

“We don’t want a case decided on partisan lines. We also don’t want a case so hurried that the work product isn’t good,” he adds.

In another landmark case, a federal appeals court in Washington Tuesday ruled unanimously that Mr. Trump doesn’t have immunity from criminal prosecution for his actions around Jan. 6. It took 28 days from oral arguments for the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals to write a 57-page ruling that “for the purpose of this criminal case, former President Trump has become citizen Trump, with all of the defenses of any other criminal defendant.”

As the Supreme Court justices are with Trump v. Anderson, the appeals court judges were operating in uncharted territory: No other former president has ever been indicted on felony charges. Mr. Trump faces 91. His attorneys have until Monday to appeal that case to the Supreme Court. If they don’t, trial court proceedings will resume immediately.

That was just a panel of three judges, however, not the full Supreme Court. And while the justices are under pressure to rule quickly, with the primaries in full swing, they are also in unfamiliar legal territory.

Ultimately, court watchers say, a decision before the term ends in June is certain. But a ruling may not come before half the country has voted in primaries and Republicans will have chosen their presidential nominee.

“There was this assumption it would come out before Super Tuesday” in early March, says Professor Magliocca. “I don’t know if they can get it done by then.

“This is an opinion that’s going to be read much more widely than normal,” he adds. “What they say might be just as important as what they do.”