Amish hair attacks: Hate crimes trial of Amish splinter group begins

Loading...

A breakaway Amish group accused of settling a score by carrying out hair-cutting attacks against members of their faith moved into the hills of eastern Ohio two decades ago following a dispute over religious differences. US prosecutors say the group spent months planning hair-cutting attacks against followers of their Amish faith.

The government on Tuesday began laying out its case against 16 men and women charged with hate crimes in the hair- and beard-cutting attacks last fall in Ohio. Such hair-cuttings are considered deeply offensive in the traditional Amish culture.

How their community came about is quite common and on the rise among the Amish. Disagreements over church discipline and how to maintain their simple way of life amid the encroaching outside world have created dozens of splinter groups. Prosecutors say the attacks were motivated solely by such disagreements.

The defendants describe what happened as internal church disciplinary matters and say the government shouldn't get involved. The defense was expected to present its case later Tuesday.

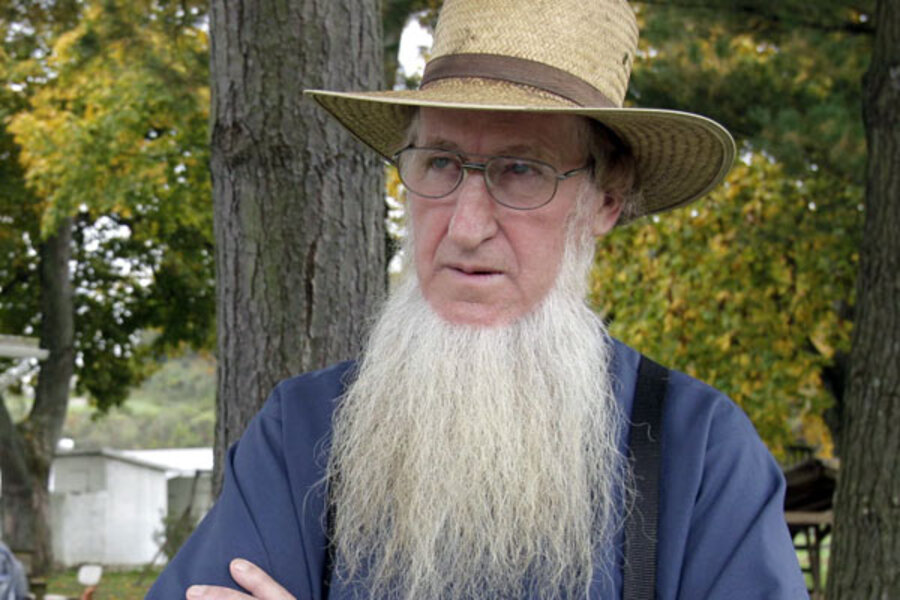

But there was something troubling about this one and its leader, according to authorities. They say Samuel Mullet Sr. allowed beatings of those who disobeyed him, had sex with married women to "cleanse them," and then, last fall, instructed his followers to cut the beards and hair of his critics.

Mullet and 15 other Amish men and women are set to go on trial Monday in Cleveland on charges of hate crimes in the hair-cutting attacks. Other charges include conspiracy, evidence tampering and obstruction of justice in what prosecutors say were crimes motivated by religious differences. They could face lengthy prison terms if convicted.

The defendants — including four of Mullet's children, his son-in-law and three nephews — say the government shouldn't intrude on what they call internal church disciplinary matters not involving anti-Amish bias. They've denied the charges and rejected plea bargain offers carrying sentences of two to three years in prison instead of possible sentences of 20 years or more.

Mullet has said he didn't order the hair-cutting but didn't stop anyone from carrying it out. He also has defended what he thinks is his right to punish people who break church laws.

"You have your laws on the road and the town — if somebody doesn't obey them, you punish them. But I'm not allowed to punish the church people?" Mullet told The Associated Press last October. "I just let them run over me? If every family would just do as they pleased, what kind of church would we have?"

The tactics Mullet is accused of violates basic principles of the Amish who value nonviolence and forgiveness even when churches break apart. "Retribution, retaliation, the use of force; that's almost unheard of," said Thomas J. Meyers, a sociology professor at Goshen College in Indiana.

Schisms within the church, which has no central authority, go back centuries and have created a range ofAmish churches with varying rules and beliefs. The Amish famously broke away from the Mennonites in 1693 over the practice of shunning church members. Another group known as the Beachy Amish formed in 1927 and soon began allowing the use electricity and automobiles.

There are a dozen groups living in Ohio's Holmes County alone, home to one of the nation's largest Amishsettlements, said David McConnell, an anthropology professor at Wooster College. The number has grown as churches struggle where to draw the line on allowing modern technology into their simple, modest lifestyle. Those decisions often revolve around dealing with young people and those who have been forced out of the church, he said.

Matthew Schrock, who left Holmes County's Amish community during the mid-1990s, said religious disputes were common and often took an emotional toll even on those not directly involved.

"When there are conflicts and you find yourself outside the accepted set, it's a very difficult place to be," he said.

Some within the community have trouble letting go following a dispute, he said, because the Amish so closely identify themselves based on their beliefs. "When someone believes something slightly different, that's a threat to my existence," he explained.

When there are splits, a new set of bishops and ministers take over. Sometimes the new group will move away but not usually. Those that are pulled apart can join together at weddings and funerals but not for worship services. Even families can be divided.

"It's a divorce within the congregation," said Karen Johnson-Weiner, a professor at the State University of New York in Potsdam who has written extensively about the Amish. "It's very, very sad and heart-breaking."

The expectation is that the breakup is the end of the dispute, she said.

"Each side says you go off and do your own thing and that's the end of it," said Johnson-Weiner. "There's an understanding that you can't judge them. It's up to God to judge the choices they make."

Mullet relocated the members of his group in 1995 to a hilly area near the West Virginia panhandle where they live on farms along a gravel road.

The 66-year-old, who has fathered at least 17 children, has denied characterizations from authorities that his group is a cult. The hair-cuttings, he said last fall, were a response to continuous criticism he'd received from other Amish religious leaders about his being too strict, including excommunicating and shunning people in his own group.

The Amish believe the Bible instructs women to let their hair grow long and men to grow beards and stop shaving once they marry.

In one of the attacks, authorities say, one couple acknowledged that their two sons and another man came into their house, held them down, and cut the father's beard and the mother's hair. They refused to press charges.