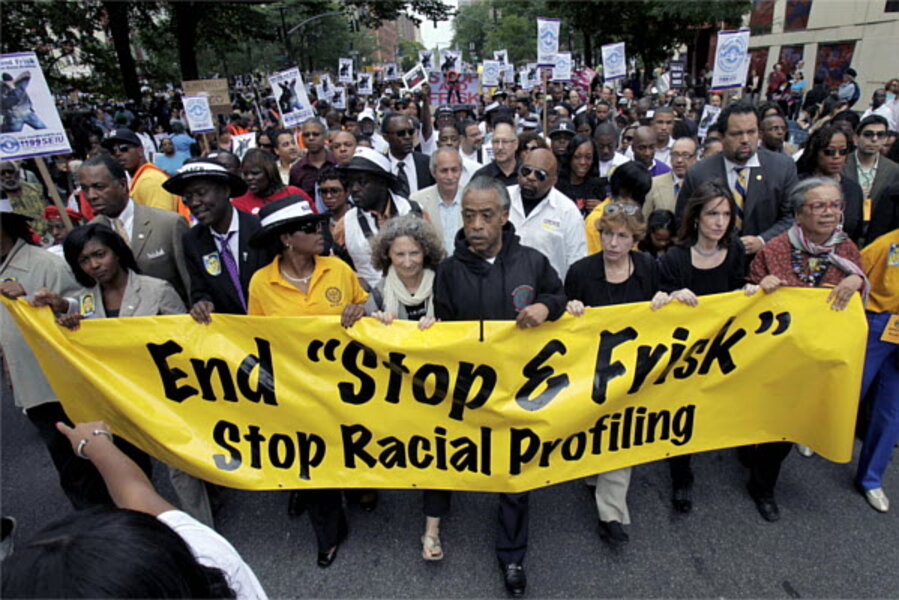

'Stop and frisk' on appeal: Should cops be 'scared' to frisk?

| NEW YORK

A federal judge's conclusion that New York City police officers sometimes violate the constitution when they stop and frisk people has made officers "passive and scared" to use the crime-fighting tactic, lawyers warned a federal appeals panel Tuesday as they asked that the ruling be suspended while it is appealed.

The three-judge 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals asked plenty of questions but did not immediately rule in a case that may be affected in a major way by next week's mayoral election. Democratic candidate Bill de Blasio, who is leading in polls, has sharply criticized and promised to reform the police department's stop-and-frisk technique, saying it unfairly targets minorities.

Attorney Celeste L. Koeleveld, arguing for the city, said officers are "hesitant, unfortunately" to use the tactic anymore.

Attorney Daniel Connolly, making legal points on behalf of former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and former US Attorney General Michael Mukasey, told judges that city officers were "defensive, passive, and scared" about using the technique.

"This decision is bad law," he said. "No one counts on federal judges to keep us safe on the streets."

Attorney Courtney Saleski, arguing on behalf of the Sergeants Benevolent Association, noted that stop and frisks were down 50 percent in the first six months of this year compared with a year earlier. She said officers were afraid stops violate the constitution.

"That means constitutional stops are being chilled and that's not good for the safety of the community," she said.

But lead plaintiffs' attorney Darius Charney for the nonprofit legal advocate Center for Constitutional Rights noted that the drop in stop and frisks came even before the judge ruled and said it was accompanied by a drop in murders and other crimes.

And Christopher Dunn, associate legal director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said it would be premature for the appeals court to stay the effect of the lower-court ruling because the police department thus far has not been required to make any changes to the program.

He said that if police officers on their own are engaging in fewer unconstitutional stops, "that's a good thing."

During legal arguments that lasted nearly three hours, two of the three judges seemed concerned about the manner in which Judge Shira A. Scheindlin reached her August findings that the police officers have systematically violated the civil rights of tens of thousands of people by wrongly targeting black and Hispanic men. She appointed an outside monitor to oversee major changes, including reforms in policies, training, and supervision, and she ordered a pilot program to test body-worn cameras in some precincts where most stops occur.

Circuit Judge John Walker said Scheindlin responded to the city and police department's staunch defense of the program as if they were former Alabama Gov. George Wallace standing in a schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama in 1963 to block the arrival of two black students.

He said reforms she ordered as part of her findings were broad and of the kind that might result when the judiciary is facing "total hostility on the part of the authorities." He likened it to what had to be "done in the deep South in the 1950s."

Circuit Judge Jose Cabranes several times questioned whether lawyers believed a district judge would, in effect, be running the police department. And he questioned the fairness of how Scheindlin ended up with lawsuits challenging stop-and-frisk tactics.

Attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff, a lawyer representing a former assistant attorney general active in Justice Department lawsuits that resulted in similar court oversight of urban police departments, told the judges that Scheindlin's remedies were similar to successful remedies carried out in Los Angeles, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati.

The stop and frisk tactic has been criticized by a number of civil rights advocates. More than 100 students and activists turned out at Brown University on Tuesday for a lecture by NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly on "Proactive Policing in America's Biggest City" — and shouted him down, prompting the talk to be canceled.