Why flying on commercial airlines keeps getting safer

| New York

More travelers are flying than ever before, creating a daunting challenge for airlines: keep passengers safe in an ever more crowded airspace.

Each day, 8.3 million people around the globe — roughly the population of New York City — step aboard an airplane. They almost always land safely.

Some flights, however, are safer than others.

The accident rate in Africa, for instance, is nearly five times that of the worldwide average, according to the International Civil Aviation Organization, part of the United Nations. Such trouble spots also happen to be where air travel is growing the fastest, putting the number of fliers on course to double within the next 15 years.

"In some areas of the world, there's going to be a learning curve," says Patrick Smith, a commercial airline pilot for 24 years and author of "Cockpit Confidential." But that doesn't necessarily mean that the skies are going to become more dangerous. "We've already doubled the volume of airplanes and passengers and what's happened is we've gotten safer."

To meet the influx of passengers, airlines will need to hire and train enough qualified pilots and mechanics. Governments will have to develop and enforce safety regulations. New runways with proper navigation aids will have to be constructed.

Industry experts acknowledge the difficulties, but note that aviation has gone through major growth spurts before and still managed to improve safety along the way.

Last year, 3.1 billion passengers flew, twice the total in 1999. Yet, the chances of dying in a plane crash were much lower.

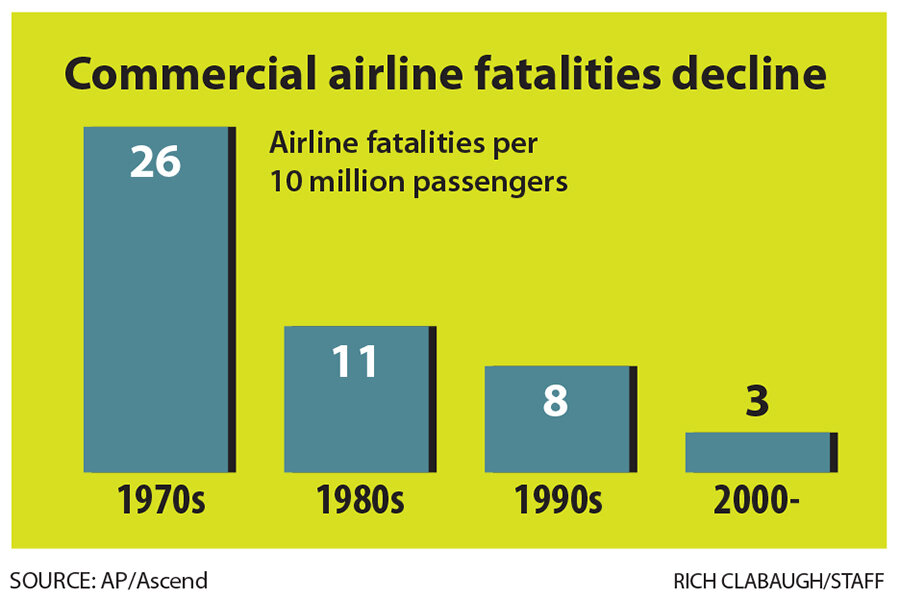

Since 2000, there were less than three fatalities per 10 million passengers, according to an Associated Press analysis of crash data provided by aviation consultancy Ascend. In the 1990s, there were nearly eight; during the 1980s there were 11; and the 1970s had 26 deaths per 10 million passengers.

The last two weeks have been bad for aviation with the shooting down of a Malaysia Airlines flight followed by separate crashes in Taiwan and Mali. But the rare trio of tragedies represents just a fraction of the 93,500 daily airline flights worldwide.

"Aviation safety is continuing to get better. A sudden spate of accidents doesn't mean that the industry has suddenly become less safe," says Paul Hayes, director of air safety for Ascend.

As global incomes rise, people in Southeast Asia, Africa, Latin America, India and China want to travel more. Airplane manufacturer Airbus says that while U.S. traffic is growing 2.4 percent a year, emerging countries are seeing 13.2 percent annual growth.

In those countries, flying is often the only option. Cities are remote. Adequate highways or railroads don't always exist. New airlines have popped up, offering affordable flights to satisfy this growing thirst for travel.

These carriers — many unheard of outside their region — are adding new jets at a breakneck pace. In the next six years alone, Indonesia's Lion Air will get 265 new planes and India's IndiGo will receive 125, according to Bank of America.

"If an airline rapidly expands," Hayes says, the challenge of adding new staff and getting them to work together properly "can increase risk."

Plane manufacturer Boeing estimates that within 20 years, the industry will need 498,000 new commercial airline pilots and 556,000 new maintenance technicians. Finding enough skilled workers to meet that demand isn't going to be easy.

Sherry Carbary, vice president of Boeing Flight Services, says there is an "urgent demand for competent aviation personnel."

"This is a global issue, requiring industry-wide collaboration and innovative solutions," she says.

Lee Moak, president of the Air Line Pilots Association, the largest U.S. pilots' union, adds that strong oversight by governments and trade groups is needed to ensure proper training.

"If you don't have a safe operation, then you're not going to have customers," Moak says.

Countries must also invest in the right infrastructure. There needs to be proper radar coverage, runway landing lights and beacons and skilled airport fire and rescue teams, says Todd Curtis, director of the Airsafe.com Foundation. Developing regions, he adds, also currently don't have enough airports that planes can divert to in case of an emergency.

And when there is a crash with survivors, having hospitals nearby with advanced trauma centers helps to lower the number of fatalities. Nearly a third of all accidents since 1959 where the plane was destroyed still didn't have any deaths, according to Boeing.

Technological improvements are also helping to lower the accident rate. Cockpits now come with systems that automatically warn if a jet is too low, about to hit a mountain or another plane. Others detect sudden wind gusts that could make a landing unsafe.

The next generation of technology promises to help prevent even more accidents. Honeywell Aerospace launched a new system 18 months ago that gives pilots better awareness about severe turbulence, hail and lightning. The company is also developing a system to improve pilots' vision in stormy weather: an infrared camera will let them see runways through thick clouds earlier than the naked eye would.

"At the end of the day, we're a safety net. We're there to help the flight crew," says Ratan Khatwa, senior chief engineer for human factors at Honeywell.

The catch: While these advances would help a generation of new pilots fly more safely, not all airlines are willing to pay for the upgrades.

"The industry is very opposed, for cost reasons, to retrofits," says James E. Hall, former chairman of the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board. "You have a situation of the haves and the have-nots."

__

Scott Mayerowitz can be reached at http://twitter.com/GlobeTrotScott.

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.