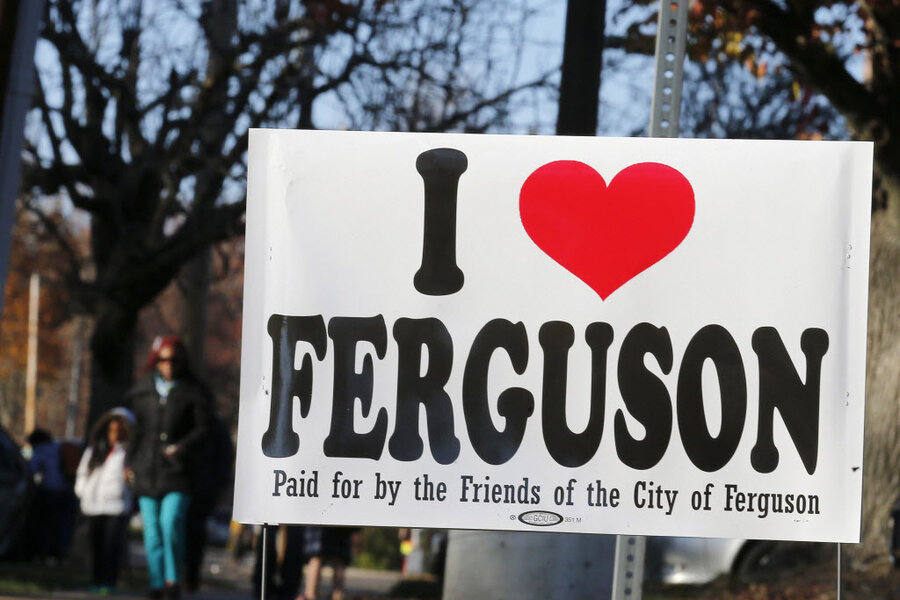

'I love Ferguson.' Neighboring city shows support, sympathy

Loading...

| Florissant, Mo.

In this quiet city just north of Ferguson, Missouri, the neat streets of small homes and shops show no signs of the racial tension that has gripped the adjacent St. Louis suburb since the fatal police shooting in August of an unarmed black teen.

In riot-scarred Ferguson, many businesses remain boarded up three months since the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Florissant shows no obvious mark of racial tensions, apart from a few "I Love Ferguson" signs put up to show support for its southern neighbor.

Residents of Florissant are well aware of Ferguson's troubles. While sympathetic to the tragic death of a teenager, they are also worried about the anger directed at police. They are also nervous that unrest could reach them if the grand jury hearing the Brown case decides not to bring charges against the shooter,Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson.

"They have reason to be angry, but they don't express it very well," said 90-year-old retiree Will Geno as he sat with some friends in Old Town Donuts, enjoying the sunshine streaming through plate glass windows.

About two-thirds of the residents of Florissant are white, a mirror image to Ferguson, which is about two-thirds black. Florissant is also wealthier, with median household income topping $51,000. That exceeds the state average of $47,000 and is well over Ferguson's $37,000, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

The two cities have long been linked. Geno recalled attending high school in Ferguson and visiting a long-gone movie house with his friends, and residents of both races said they had gotten along well for years.

Despite that history, some are wary that violence sparked by the police shooting could spread if the grand jury decides not to charge Wilson.

"I'm hoping that we can have a peaceful settlement. I hope we don't go back to what it was like last time. I was in the military during the 1960s race riots and it's sad to be seeing all of that all over again," said Jim Guerin, a 65-year-old resident of Florissant who is black and drives a bus part time in his retirement.

Sitting with friends at a bowling alley, Guerin said he doubted any coming protests would be confined toFerguson.

"It's going to be all over St. Louis County," Guerin said.

Some in Florissant said they do not understand why protesters in Ferguson have repeatedly clashed with police.

"I don't like they way they're treating the police," said Julie Griffith, 66, who was tending the counter at a small shop on Friday morning for a friend. "If you're demonstrating and they tell you to stay on the sidewalk, why can't you stay on the sidewalk? Why is that so hard?"

For their part, activists in Ferguson contend that local police often sparked conflicts with protesters in August when they took a heavy-handed approach by aiming rifles and firing tear gas at crowds, measures that police said were necessary to protect themselves and the public.

"I do think the police need to have some sensitivity training, how to handle people," said Guerin. St. Louis County police said that since August, officers have been sent through fresh training on de-escalating conflict.

Activists have also pledged to respond in nonviolent ways to the grand jury's decision. They blame the incidents of burning and looting in August on a handful of violent actors.

As he worked at Florissant's Old Town Marketplace consignment shop, Gary Ponder, 59, said he sympathized with protesters' anger but also hoped to see a less confrontational tone if further demonstrations develop.

"I have problems with the government too, I think we are overtaxed and underrepresented. You want to speak out, I'm there. But throwing rocks, spitting on cops? That's over the line," Ponder said. "This isn't a black and white issue, it's a right and wrong issue." (Reporting by Scott Malone; Editing by David Gregorio)