Unseen foe for troops: sexual assault in US military

Loading...

| Washington

When US Army Sgt. Andrea Neutzling was raped by two fellow soldiers during a yearlong deployment in Iraq in 2005, she recounts, she decided not to say anything to her commanders. She had previously reported a sexual assault by a colleague, with little consequence, and didn't want to be viewed as a troublemaker, she says. She simply slept on a cot, her rifle pointed toward the door, for days afterward.

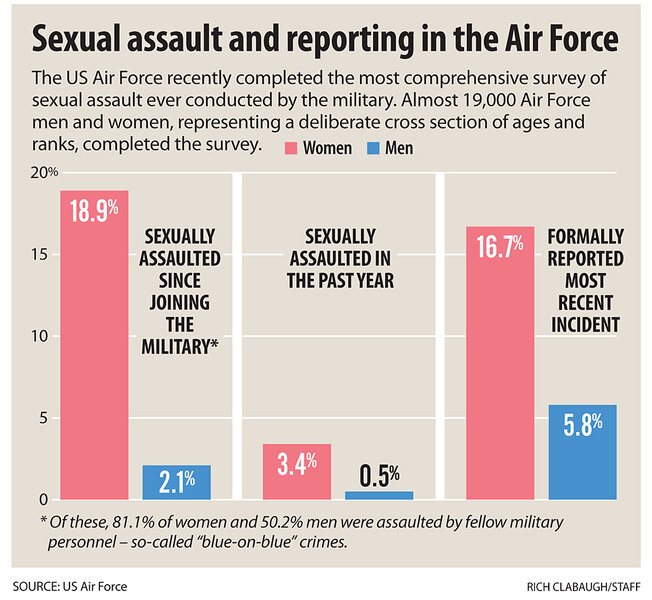

Throughout the military, sexual assault – which affects about 19 percent of female troops and 2 percent of males, according to the most comprehensive survey of sexual assault ever conducted by the US military – is rarely reported. Released last month, the survey of Air Force personnel found that "less than 1 in 5 women and 1 in 15 men" filed a formal report after their most recent sexual assault.

Half of the female airmen who reported being raped said they chose not to report the attack for "fear of being treated badly" or because they "did not want to cause trouble" in their unit. Nearly a third said they did not trust the reporting process.

Top military officials acknowledge the need for change. "This crime threatens our people, and for that reason alone it is intolerable and incompatible with who and what we are," said Gen. Norton Schwartz, Air Force chief of staff.

Bipartisan legislation under way

Reps. Niki Tsongas (D) of Massachusetts and Mike Turner (R) of Ohio have proposed legislation to address the crime and to encourage more victims to come forward.

Of those few troops who do report sexual offences, even fewer see their attacker face justice, these representatives note. While 40 percent of civilian allegations are prosecuted, "this number is a staggeringly low 8 percent in the military," they said in a joint statement.

The bill ensures that conversations between assaulted service members and victim advocates remain confidential. Currently, those conversations can be subpoenaed.

The bill also calls for more training of sexual assault response coordinators, or SARCs, and requires them to hold full-time Defense Department positions, not be hired as contractors.

Better-trained SARCs could have helped Air Force Sgt. Marti Ribeiro after an officer in her unit raped her when she took a smoking break – 10 feet from the guard station, behind a large generator – while on guard duty at a base in Afghanistan, in 2006.

After the rape, she says, she completed her guard duty shift, then looked for a sexual assault coordinator. "I didn't take a shower, I didn't wash my hands," Ribeiro remembers. "I'd watched 'Law & Order' and thought to myself, 'I'm going to do exactly what [character] Detective Benson says' ... so they can swab and do the rape kit."

After Ribeiro told the SARC what had happened, "Her first question was, 'Where was your weapon?' " – implying, it seemed to Ribeiro, that she should have been able to defend herself.

Ribeiro's answer prompted the coordinator to send her away. "Because I'd left my weapon in the guard shack, she told me I would be charged with dereliction of duty." Ribeiro returned to her base housing and did not speak about the attack for six months.

The SARC had failed to advise her that she could receive a rape kit (she didn't), that she could save the evidence in case she chose to pursue a charge later, or that she could not be charged for details included in a confidential reporting of the crime. "You don't think about those things at the time," Ribeiro says. "You're just in survivor mode."

Ribeiro was never given the chance to speak to a military lawyer, a point the new legislation would address. Currently, defendants in the military are guaranteed a lawyer, but victims are not.

The legislation would also allow victims of sexual assault to transfer out of their base or unit. Troops of junior rank "are given few privileges and barely any freedom of movement to flee their perpetrators, to seek help when they need it most, or to leave the units or bases where they are being brutalized," says Anuradha Bhagwati, a former US Marine captain and executive director of the Service Women's Action Network.

After Neutzling discovered that the two men who had raped her had videotaped the attack – and were showing the tape to friends – she told a colleague she "wanted to maim them," Neutzling recalls. The colleague reported this news to a chaplain, who told her that she "didn't act like a rape victim," and then took away her M-16, Neutzling says.

Because she had not reported the rape or completed a rape kit, her superiors told her "it was a matter of 'he said, she said,' or in my case, 'they said, she said.' " Furthermore, because she was married, "since I admitted having sexual relations with them, I was told by command that I was committing adultery, and if I wanted to push it I would be brought up on adultery charges."

Sexual assault victims are all too often "punished again by insensitive or negligent commanders," Ms. Bhagwati says.

Both women finished their deployments, seeking help again only after they returned to the United States and retired from the military.

In addition to the harm done to the victims of sexual assaults, the military as a whole pays a price for these crimes in losing dedicated and skilled personnel. Ribeiro was a third-generation service member whose grandfather was in the Army Air Corps and whose father had served in the Air Force for 28 years. One more heartbreaking aspect of the rape, Ribeiro says, "is that I absolutely loved my job." She would have been interested in a military career, she said, had it not been for the assault.

Like Ribeiro, Neutzling was committed to her job and had no plans to retire, prior to the assaults. Instead, in February, Neutzling joined 16 other plaintiffs filing a federal lawsuit that alleges the Pentagon did not "take reasonable steps to prevent plaintiffs from being repeatedly raped, sexually assaulted, and sexually harassed by federal military personnel."

The military's response

Preventing sexual assault "is now a command priority, but we clearly still have more work to do in order to ensure all of our service members are safe from abuse," said Pentagon spokesman Geoff Morrell, in response to the lawsuit.

The military has begun to make changes to address sexual assault. Victim advocates must now volunteer for the position. Previously, it was an assigned job, sometimes used as extra duty or punishment.

The Pentagon has also launched formal training programs to encourage bystanders to stop a sexual assault. "Every airman has the moral obligation and professional duty to intervene appropriately and prevent an assault, even when it means taking difficult or unpopular actions," said Secretary of the Air Force Michael Donley and General Schwartz in a statement.

The military is also hiring more sexual assault investigators and focusing on better training for military lawyers, who often have little experience with sexual assault cases.

Neutzling's daughter, now 8, is talking about joining the military – a career Neutzling says she might support, as long as the military is "safer for her," she says, "than it was for me."