End of Pentagon transgender ban means no more 'tiptoeing' for this Marine

| Washington

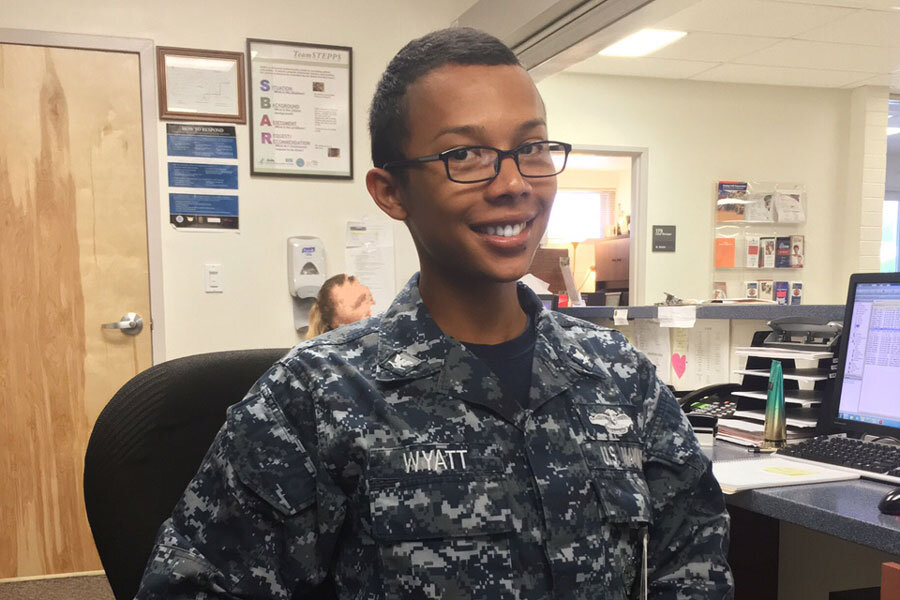

It was the assignment that changed Corpsman Akira Wyatt’s life.

In 2014, a United States Marine on shore leave in the Philippines discovered that the sex worker he had hired was transgender and killed her in a hotel bathroom.

The Marine, Lance Cpl. Joseph Scott Pemberton, was brought to Corpsman Wyatt’s ship for medical care following his arrest.

That was the moment Wyatt, born in the Philippines to a Filipina mother and a Marine father, decided she needed to come out as transgender and transition. It was “very scary” treating Lance Corporal Pemberton, she says, but it was important to her to provide good care.

“He was such a young kid –19 years old – and had probably just finished boot camp and got deployed,” she says. “When I saw him I thought, ‘I’m going to take care of him, make sure he’s good.’ ”

On Thursday, Wyatt was celebrating what she calls “the happiest day of my life.”

The Pentagon announced it was lifting its ban on transgender troops serving in the US military, ending the days of “tiptoeing” and moments of awkwardness for Wyatt and her fellow service members. The decision marks the latest in a series redefining who may serve in the military, starting with the lifting of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” ban in 2011 and the opening of all combat jobs to women this year.

In the months leading up to the announcement, Defense Secretary Ash Carter and other Pentagon officials “talked with a lot of us and heard our experiences,” Wyatt says. “Now we’re there. It’s finally done.”

In a Pentagon briefing Thursday, Defense Secretary Carter called himself “proud of what this will mean for our military, because it’s the right thing to do.” That said, he added, “I think it’s fair to say that this has been an educational process for many people in the department, including me.”

Carter said that throughout the decision-making process, he has been guided by one central question – one highlighted by Wyatt’s experience: “Is someone the best qualified individual to accomplish a mission?” Bringing in good people to the armed forces, he added, is “the key to the best military in the world.”

A RAND study estimates the number of transgender individuals currently actively serving in the U.S. military at between 1,320 and 6,630 out of a total of about 1.3 million service members.

Critics questioned whether the decision would improve the battle readiness of the US military. Texas Rep. Mac Thornberry, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, issued a statement calling the lifting of the ban the latest example of “the Pentagon and the President prioritizing politics over policy.” “Our military readiness – and hence, our national security – is dependent on our troops being medically ready and deployable,” he said.

The lifting of the ban also involved complicated details such as figuring out transgender medical care, should troops need it. Such care “is becoming common and normalized,” Carter said, adding that more than one third of Fortune 500 companies, including Boeing, CVS, and Ford Motor Co., now provide coverage, up from zero in 2002.

“All of this represents a sea change from over a decade ago,” he said. Transgender troops currently in the US military will have access to this care. For prospective new transgender recruits, the rule will be that they will be required to have already undergone their transition and “be stable in that state” for 18 months before they enter the military.

For those who may realize they are transgender after joining the military, any care “determined to be medically necessary will be provided like any other medical care,” Carter said. That means if it is not deemed urgent, troops may need to wait, “because if they need to be deployed, they need to be deployed,” he added.

For Wyatt, it means she can continue her career as a military nurse, treating patients. “I want to continue in the military. I love being a hospital corpsman. I love treating patients – it’s the best world that I could be in,” she says.

When she enlisted, her father “told me that the world can be rough out there, being a Marine, but he told me to always be confident in what you do, always be a good person, always be a kind person,” she recalls. “He gave me a lot of great pointers.”

These were pointers Wyatt called on when she had to dig deep, particularly when caring for Pemberton, who was convicted of the crime last December. But the experience made her realize that she wanted to be open about who she was with her fellow Marines.

As she did, many of them were “very supportive” and “very happy for me that I came out,” she says. “One thing they did was ask me a lot of questions. They wanted to understand. They wanted to learn who I was as a person, and who I wanted to be.”

But her honesty also created a “rough patch” with other colleagues. Defense Department policy prior to the lifting of the ban directed personnel to refer to service members by their gender at birth.

“For them, I was male, and so that was that,” Wyatt says. But she adds that “a lot” of her coworkers and those within her chain of command “have made an effort to call me the ‘she’ pronoun, and to be with me in my transition, to go through my journey.”

That said, “Now that the policy has changed, it’s easier for them to relax,” Wyatt adds. “So they won’t be afraid or have to tiptoe around ‘he’ or ‘she.’ ”