Romney's decisive win in Michigan scrambles G.O.P. field

| Chicago

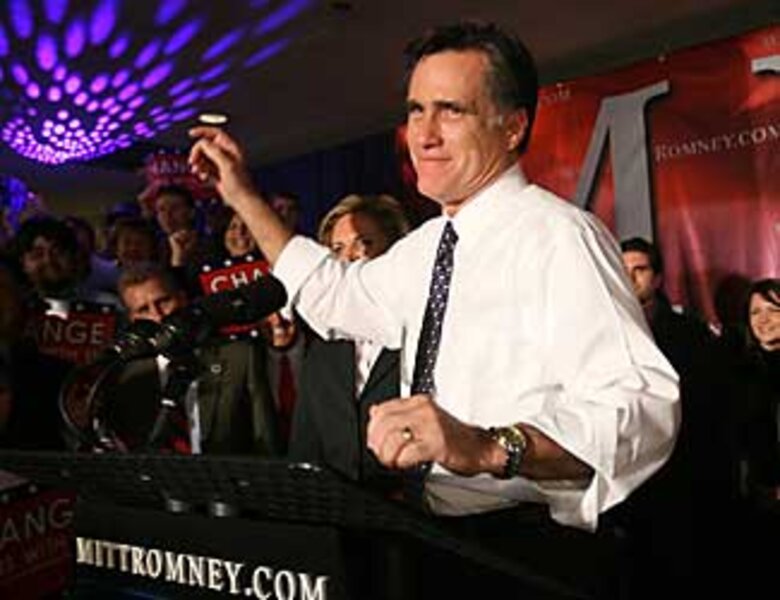

Mitt Romney scored a decisive victory in Michigan Tuesday night, beating out Sen. John McCain in a race many viewed as a must-win for Mr. Romney to remain viable for the Republican presidential nomination.

"Tonight is a victory of optimism over Washington-style pessimism," he told cheering supporters in his victory speech, continuing the Washington-outsider image he has cultivated in recent weeks.

It is Romney's first major win, and it leaves a wide-open Republican race even more murky, as the candidates head into South Carolina's primary on Saturday. Romney, Senator McCain, and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee each have one victory under their belt.

"The Republican party has gone from confusion to uncertainty," says Jack Pitney, a government professor at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, Calif. "There's no clear front-runner, and the race is going to be very exciting for the next couple of weeks, at least."

Romney took in 39 percent of the vote, compared with 30 percent for McCain and 16 percent for Governor Huckabee. Less attention was paid to the Democratic primary, where Hillary Rodham Clinton won 55 percent of the vote, compared with 40 percent for "uncommitted." The other major Democratic candidates had taken their names off the ballot after the national Democratic party chastised Michigan for moving its primary up in the calendar.

Romney seemed to be helped by several factors in Michigan, including his own status as native son whose father was a three-term governor and chairman of American Motors Corporation. In the past week, Romney, a former Massachusetts governor, worked to remind Michiganders that he was one of them.

His rallies and TV ads focused heavily on the economy, an issue of particular concern in Michigan, which is already in recession with a 7.4 percent unemployment rate.

Exit polls showed that 55 percent of voters considered the economy to be the most important issue, compared with 17 percent who cited the Iraq war and 13 percent who said illegal immigration. Among those voting on the economy, Romney beat McCain 42 percent to 29 percent.

Romney also benefited from Michigan's relatively low turnout and that few independents – a group that generally favored McCain and who many expected would come out in large numbers – voted in the primary. The large numbers of Michiganders who made up their mind in the past three days favored Romney as well.

McCain made several big errors in the state, including his "straight talk" admission that some of the jobs lost in Michigan aren't coming back and his overt appeal to independents and Democrats, says Bill Ballenger, editor of the "Inside Michigan Politics" newsletter. "Romney came in and seized the economic issue and he really went after it – it's such a big factor here compared to the first two states," says Mr. Ballenger. "Even though McCain was the guy with the foreign-policy credentials, the fact is that the war on terror and Iraq are way down the list from the economy here in Michigan."

That's starting to be the case across the country, too, as many polls show the economy topping the Iraq war in importance to voters. Romney's success playing off that issue in Michigan – he emphasized his desire to bring private-sector expertise and efficiency to Washington – may bode well for him as he moves on.

"The fact that he was able to capitalize on economic discontent – that's something that's likely to become an even bigger factor in other states as the national economy weakens," says Darrell West, a political scientist at Brown University in Providence, R.I. "Romney tested his economic message in Michigan and did very well."

Still, Romney faces an uphill battle in the next major contest in South Carolina, where he's unlikely to do well. Most political experts say the field is still wide open, with Romney and McCain perhaps in the best positions, but with Mr. Huckabee and former New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani in the race as well.

At this point, the race shifts from the typical tactic of achieving an aura of inevitability as candidates work to amass delegates to win the nomination. It's no longer clear that a consensus nominee will emerge even after 22 states weigh in on Super Tuesday Feb. 5.

"It's a race about arithmetic," says Dr. Pitney. "For many years, the assumption about the nomination contest was that one candidate would jump out to lead and everyone else would fall, like a check-mate in a game of chess. But now it's a counting game, not a chess game."

Huckabee, say many analysts, was a loser in Tuesday's primary. Though he only actively campaigned in the state for about a week, his economic populist message seemed to resonate among some Michiganders, and he had hoped to do better than the 16 percent he ended up winning. He didn't manage to win even among the more social conservative, evangelical voters in western Michigan, who tended to vote instead for Romney.

"If Huckabee doesn't do well in South Carolina, then he's gone multiple times without his name being talked about on the national scene," says Ed Sarpolus, an independent pollster in Lansing, Mich.

Mr. Giuliani, who has staked his campaign strategy on a win in Florida on Jan. 29, also performed poorly, garnering just 3 percent of the vote, and less than Rep. Ron Paul of Texas and former Sen. Fred Thompson of Tennessee.

As the GOP race turns into what looks like a long, grueling contest, many experts say money is likely to be a major factor going forward. Romney, who has a large personal fortune he has already tapped, is better positioned than other candidates. McCain, however, may be able to capitalize on his win last week in New Hampshire to ramp up fundraising.

McCain, who tends to appeal to independent voters more than hard-core Republicans, may be hurt in closed-primary states that don't allow independents to vote, says Dr. West. But he's also higher in the national polls, where Romney has been lagging.

"This is like political soap opera," says Denise DeCook, a Republican Party strategist and vice president for public affairs for Marketing Resource Group in Lansing. "It's really one cliffhanger after another."

Ms. DeCook says that in watching Romney over the past week, she was struck by the change in tone in his campaign. His appearances seemed more personal and less structured, she says. "Romney caught his stride and found his voice as a native son," she says. "I think he needed this badly."