South Carolina: It used to be Edwards country

| Columbia, S.C.

Constance Kilgore voted for John Edwards four years ago, but the former senator, a South Carolina native, was scarcely on her mind Monday as she listened to the three leading Democratic candidates speak at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day rally here.

"Edwards? He's good also," said Ms. Kilgore, a high school janitor who traveled to the State House from Spartanburg, an hour and a half away. "But on account of Miss Clinton being a woman and Obama being an African-American, it's different now."

No one has to tell Mr. Edwards that. South Carolina rewarded Edwards with his only victory in the 2004 primaries – a 45 percent to 30 percent win over Sen. John Kerry. This time, he remains a faraway third in the polls, his favorite son pitch no match for his rivals' celebrity, especially among black voters, who make up half the Democratic voters here.

In a Rasmussen poll released Wednesday, Edwards drew just 6 percent of the African-American vote here, compared with 68 percent for Sen. Barack Obama and 16 percent for Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton. Edwards is faring better with white South Carolinians, but still trails Senator Clinton by a large margin ahead of the Democratic primary Saturday.

The inertia of his candidacy here has vexed Edwards and his supporters, who had counted on the state to help pierce perceptions of the Democratic contest as a two-person battle. A significant loss in his native state is likely to renew questions about his staying power and his reasons for staying in the race.

"I think it's the same problem I have everywhere – we have overwhelming national publicity for two candidates," Edwards told reporters after a campaign stop in Winnsboro, S.C., earlier this week. "When I get heard in the African-American community, they'll understand that I'm the strongest proponent of doing something about poverty, for universal healthcare, for raising the minimum wage, for a whole group of things that directly impacts the African-American community."

But even some of his strongest supporters concede there was little he could do here to blunt the historymaking candidacies of his rivals. Senator Obama is the first African-American with a strong chance at his party's nomination, and Clinton, the first woman. Her husband, Bill Clinton, was so close to the African-American community he was nicknamed "the first black president."

"There's no doubt that the dynamics of the 2008 race are way, way different than 2004," says Ken Campbell, chairman of the county Democratic Party in Seneca, S.C., the town in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where Edwards was born.

Edwards placed second in Iowa and third in New Hampshire and won just 4 percent of the vote Saturday in Nevada. But he continues to pledge a coast-to-coast fight for the nomination.

Some analysts suspect he may try to amass enough delegates in the Super Tuesday primaries on Feb. 5 to play "kingmaker" at the national conventions this summer, particularly if neither Obama nor Clinton draws enough before then to claim the nomination. But that is a risky strategy, especially if staying in the race diverts votes from Obama, whom he appears to favor over Clinton.

Others offer a less cynical view. In the face of what many analysts see as insurmountable losses, Edwards is subtly recasting his candidacy from a quest for the White House into an extension of his fight against poverty. "This is the cause of my life," he told reporters Sunday outside Zion Baptist Church in Columbia. At the Democratic debate in Myrtle Beach the next day, Edwards said, "Fighting to end poverty in America may not get you any votes, but it is the right thing to do."

"He's not doing anything else with his life right now. He doesn't have an office. He doesn't have a job," says Ferrel Guillory, an expert on Southern politics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "Here's an opportunity for him to continue to shape the public dialogue."

Still, there is a little doubt about the import of South Carolina in his fight for relevancy. He has visited more often and raised more money here than his rivals. His campaign aired 3,621 television spots in the state in November and December, according to Nielsen figures, more than double Obama's and Clinton's combined.

He has missed no opportunity to remind voters of his roots here, holding "Homecoming Rallies," a "Bringing It Home" bus tour, and, this week, a "Back Roads, Back Home Barnstorm" to highlight his ties to rural America.

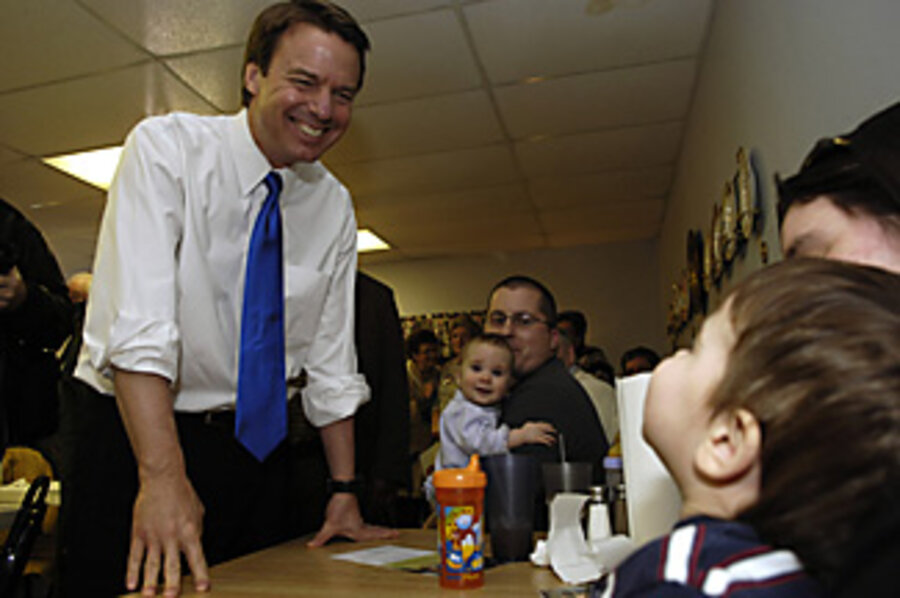

In theory, his antipoverty, anticorporate message should have played well in South Carolina, which has lost thousands of jobs in recent years as factories have closed or moved overseas. But his campaign stops here have seen fewer news crews and thinner crowds than they did in Iowa and New Hampshire. At a buffet-style cafe in Winnsboro Sunday, Edwards shook hands with supporters but gave no remarks.

Standing in a corner of the cafe, Jackie Mincey, a retired restaurant owner, said he lit on Edwards through a process of elimination. "I ain't voting for no woman, and I ain't voting for no black," he said. "There ain't no one left but Edwards."

In some ways, say analysts, Edwards's sagging fortunes here this time go beyond Clinton and Obama.

Edwards, who moved as a boy to North Carolina, where he became a trial lawyer and senator, ran in 2004 as a Southern populist against a Massachusetts liberal. Even then, his chief appeal was to white South Carolinians. Edwards trounced Senator Kerry among whites, 52 percent to 27 percent, but narrowly edged past Kerry, 37 percent to 34 percent, among blacks.

African-Americans in the South tend to be warmer to northern liberals – whom many associate with the civil rights movement – than do its whites, says C. Danielle Vinson, a political scientist at Furman University in Greenville, S.C.

Some Democrats say Edwards has failed to refresh the message and strategy that worked for him here in 2004. "He's relying on his past laurels very strongly and unwisely," says Waring Howe, chair of the Charleston County Democratic Party and a member of the Democratic National Committee. Mr. Howe endorsed Obama last week.

Edwards has complained bitterly of his rivals' "celebrity" treatment in the media. But this week, he sought to steal some for himself. He was a guest on the Late Show with David Letterman, stumped in South Carolina with actor Danny Glover, and taped an interview to air Friday on The Tyra Banks Show.

On Thursday morning, his campaign announced a new 90-second Web ad, which will appear in the guise of a film trailer. Its title: Native Son: The Movie.