From mistakes, Clinton has learned, adjusted

| Washington

Sen. Lindsey Graham, a conservative Republican from South Carolina and longtime backer of John McCain, has called Hillary Rodham Clinton "a smart, prepared, serious senator" with an ability to "build unusual political alliances on a variety of issues."

Former Sen. Rick Santorum (R) of Pennsylvania, another conservative who collaborated with Senator Clinton on legislation, calls her "much more of a uniter" in the Senate than her rival for the Democratic nomination, Sen. Barack Obama of Illinois.

Senator McCain himself, the presumptive GOP nominee, gets along famously with Clinton. Clinton's husband, the former president, likes to joke that if they're the nominees, the campaign would be so civilized "they'd put the voters to sleep."

Whether Clinton will go head to head against McCain in November remains an open question, as she seeks to overtake Senator Obama, the Democratic frontrunner. But she and her surrogates persist in touting her experience as her top qualification for the presidency.

The kind words of current and former GOP Senate colleagues may not do her much good, though, in a primary contest where "change" has trumped "experience." The campaign doesn't much play up her success in becoming "one of the boys" in the world's most exclusive club. "Too much inside baseball," says a campaign strategist. The irony for Clinton is that, of the three major-party candidates left in the race, voters see her as most divisive and Obama as most able to unite the country.

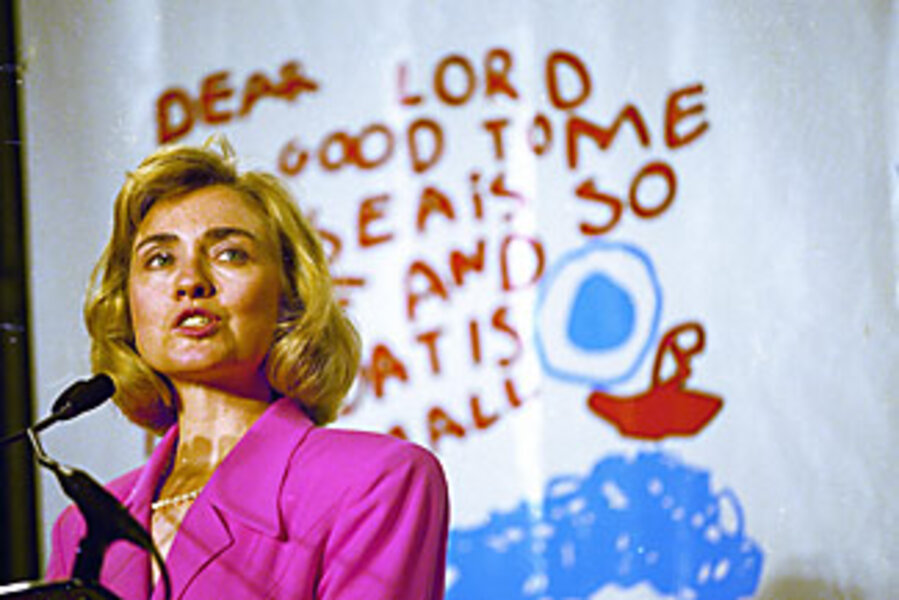

Clinton's image as "polarizing" goes back to her days as first lady of Arkansas, when she worked as a partner at the Rose Law Firm and raised eyebrows by keeping her maiden name. Arkansans – and the American public, in general, she would learn – were accustomed to more traditional first ladies who tended to focus on noncontroversial causes and hostessing duties.

But the reality is more complicated. Interviews with people who have worked with Clinton throughout her career – from her days as chairman of the board of the Children's Defense Fund to her two terms as first lady of the United States to her seven-plus years in the Senate – reveal a woman who has evolved from an advocate to a politician, learned from her mistakes, and had experiences unlike any other presidential candidate in US history.

Central to Clinton's argument that she should be the next president is her experience as first lady of the United States, a role that the Clintons treated as a top advisory position – equal, especially early on, to the vice president.

David Gergen, a veteran of Republican administrations and an early adviser in the Clinton White House, refers to their governing arrangement as a "copresidency." Clinton herself speaks of having had "a front-row seat on history." Bill Galston, another senior Clinton White House adviser, says neither characterization works; copresident is "obviously hyperbole," while merely having a ringside seat "goes too far in the other direction."

The travails of healthcare reform

Clinton as first lady is most famous for her ill-fated attempt to reform America's healthcare system, an assignment she and her husband unveiled amid great fanfare and that, ultimately, came to symbolize the disastrous first quarter of the Clinton administration – and contributed to the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994. In their effort to restructure one-seventh of the American economy, Clinton and her team had formulated a complex plan that tried to "do too much, too fast," Clinton writes in her memoirs.

The list of miscalculations is long: The Clintons misjudged the values of the country, the president's political strength, the Congress, and interest groups, Mr. Gergen writes in his book "Eyewitness to Power." They eschewed compromise, allowing the perfect to become the enemy of the good. Still, Gergen – who had his differences with the first lady – describes her as "brilliant and articulate."

"But to assign her primary responsibility for designing the program and navigating its passage through Congress was to place upon her more of a burden than any first lady could bear, even Mrs. Clinton," he concludes.

After the failure of health reform, Clinton scaled back her public profile, as her recently released White House schedules demonstrate. But it would take until early 1997 for her unfavorable ratings in the Gallup poll to sink below 40 percent, even there, a high number for a first lady. Clinton's role in various controversies – beginning with the firing of the White House travel office staff in 1993 and on through various aspects of the Whitewater scandal, including the missing Rose Law Firm billing records that turned up in the White House residence after almost two years of searches and subpoenas – contributed to her high negatives. To this day, she suffers from a perceived "honesty gap" when compared with both Obama and McCain. In mid-March, Gallup found 44 percent of the public sees her as "honest and trustworthy" versus 63 percent for Obama and 67 percent for McCain.

But through it all, she never lost her focus on healthcare.

Former White House Chief of Staff Leon Panetta recalls how, within a few months of the demise of the Health Security Act, she took on the health issues of Vietnam veterans. "It was her initiative," says Mr. Panetta. "We had some good meetings; she led the discussion."

Behind the scenes, Clinton also threw her weight behind a plan to provide health coverage for children of working parents who did not qualify for Medicaid but could not afford private insurance. The program now known as S-CHIP – the State Children's Health Insurance Program – was signed into law by Bill Clinton in 1997 and today covers 10 million children.

In her presidential bid, Clinton has touted S-CHIP as one of her signal achievements as first lady, though not without pushback. After it was discovered that she had embellished a story about a visit to Bosnia in 1996, the veracity of all her campaign claims has been called into question. In the case of S-CHIP, Clinton came out on top, despite recent press comments by Sen. Edward Kennedy (D) of Massachusetts, an Obama supporter, and other senators that she had little to do with the legislation. Curiously, in her own memoirs, S-CHIP merits only two sentences. But on balance, concludes the nonpartisan Factcheck.org, Clinton "deserves plenty of credit, both for the passage of the S-CHIP legislation and for pushing outreach efforts to translate the law into reality."

Chris Jennings, health policy coordinator for the Clinton White House, says Clinton was by far the strongest advocate within the administration on children's health policy, and that it took a lot of people – the first lady, Senator Kennedy, other members of Congress – to get the reform through.

"She was sensitive to the political dynamics" post-healthcare reform, says Mr. Jennings, now an informal adviser to her campaign. "She cared more about outcomes than about credit."

Learning the price of compromise

By the end of Bill Clinton's first term, Hillary had learned a second important lesson about life in Washington: The compromises required in passing major legislation can turn an idealist into a pragmatist – and exact a big personal cost. The issue was welfare reform, and for the first lady, more than two decades of advocacy for children ran into the political reality that the new system could allow some children to fall through the cracks.

By the 1990s, the nation was ready for change. The old welfare system from the 1930s had evolved into one that encouraged government dependence. The question was, would the new system and its five-year lifetime limit provide enough supports to help people – typically, low-skilled single mothers – move successfully from welfare to work?

In her memoirs, Clinton calls the legislation "far from perfect" but justifies backing her husband's decision to sign it by citing "pragmatic politics." The year was 1996, and President Clinton faced a Republican-controlled Congress with an activist House speaker, Newt Gingrich, at the helm. The president had vetoed the first two versions of reform, and if he vetoed the third, the first lady felt he would be handing the Republicans a "potential political windfall."

Her endorsement of the reform outraged some loyal supporters, including her mentor, Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children's Defense Fund. Clinton had interned for Ms. Edelman while in law school and, as first lady of Arkansas, was chairman of CDF's board. Edelman's husband, Peter, resigned his post as an assistant secretary for Health and Human Services in protest.

"In the painful aftermath, I realized that I had crossed the line from advocate to policy maker," Clinton writes in her book "Living History." "I hadn't altered my beliefs, but I respectfully disagreed with the convictions and passion of the Edelmans and others who objected to the legislation. As advocates, they were not bound to compromise…."

Her rift over welfare with the Edelmans, she writes, was "sad and difficult."

Acquiring foreign-policy credentials

Clinton remains the only first lady to have had an office in the White House's power center, the West Wing. In many important respects, she did operate at the level of a top aide or even the vice president.

But she did not have a security clearance or attend National Security Council meetings, and despite her talk of having visited some 80 countries as first lady, her efforts on the campaign trail to turn some of them into major diplomatic ventures have backfired.

Earlier in the primary season, Clinton trumpeted her role in bringing together Catholic and Protestant women in Northern Ireland, in an apparent effort to show that she was instrumental in settling the overall Northern Ireland conflict. Her anecdote set off a battle of claims and counterclaims by others involved in the peace process, leaving a haze over the whole story. As a result, a part of the press narrative is that candidate Clinton has a tendency to exaggerate her role in the successes of her husband's administration.

Her five-plus years on the Senate Armed Services Committee may in fact give more heft to her claims of defense and foreign-policy expertise than her travels as first lady. After two years as the junior senator from New York, she fought hard to join Armed Services – the first New York senator ever to serve on that committee.

"She did that to shore up her commander-in-chief credential," says Michelle Swers, a political scientist at Georgetown University who has studied Clinton's Senate career. "She already had two strikes against her – one, that women are generally not perceived as stronger on defense; the other, that her name was Clinton. Bill had bad relations with the military. She had to repair both of those things."

Clinton spent time courting the services, meeting with generals, and studying the issues, in addition to protecting New York military bases. Ms. Swers calls Clinton's effort a success. "Between her and Obama, she's seen as the one who's experienced on national security," she says.

An uneven leadership record

Clinton's résumé as an executive is thinner. The travails of her presidential campaign, the largest enterprise she's ever headed, do not bode well. By many accounts, her team has not worked well together, and after months of internal strife, a conflict of interest with an outside client forced Mark Penn out of his perch as chief strategist (though he remains a pollster for the campaign). Her campaign's finances have also not been well managed, forcing her to loan herself $5 million.

Even so, past colleagues speak well of her as a leader.

"She had an excellent leadership style," says Winifred Green, a board member of CDF during Clinton's years as chairman, 196-92. "That is, she would let people talk and say what was on their mind. And I would describe her leadership style as consensus-building."

Many of her old White House colleagues also praise her for her professionalism, particularly in comparison with her husband.

"She certainly was always in my mind much more disciplined than he was in terms of organization and always had a very efficient staff operation," says former Chief of Staff Panetta. "She was able to make decisions a lot more cleanly than even the president in the sense that once she made a decision, she stuck to it. When he made a decision, he continued to ponder it."

Clinton's style as a senator can be seen as an outgrowth of her time as first lady. "She learned in the White House years something about politics as a process that has to involve people and engage them," says Mr. Galston, the former White House domestic-policy adviser. "It's something you do with people, not to people."

Her joint ventures with Republicans seem to give her particular pride – and not just any Republicans, but some of the most high-profile conservatives imaginable, many of whom worked hard to have her husband thrown out of office during the Monica Lewinsky scandal. In 2005, she found common cause with then-House majority leader Tom DeLay on improving the foster-care system. She and former House Speaker Gingrich have appeared together to promote healthcare legislation. With Senator Graham, a one-time House impeachment manager, the issue was improving healthcare benefits for veterans.

Of course, anyone seeking publicity for his or her cause knows that working with Clinton guarantees TV cameras. And her bipartisan efforts have tended to be on smaller issues. Certainly, she can't compete with McCain on his bipartisan work on such major issues as campaign finance and immigration. (McCain was also a member of the Gang of 14, which successfully forged a compromise in 2005 on federal judicial nominations. Clinton did not join the group.)

But for Clinton, appearing relaxed and jovial with Republicans may mitigate some of the intensely partisan views of her. And there's no doubt she knows how to mix it up with the guys.

Then-Senator Santorum recalls walking by Clinton one day in 2005 on Capitol Hill, surrounded by a gaggle of reporters. He had just published his book, "It Takes a Family" – a conservative look at public policy – and, in a way, a reply to an earlier book by Clinton.

"Remember, Rick," she called out, "it takes a village!"

"She was joking – but in every joke there's something," he says. "So was it a little dig? Yeah, it was both. But it was nicer…. I took it in good spirit."