How the candidates' speaking styles play

Loading...

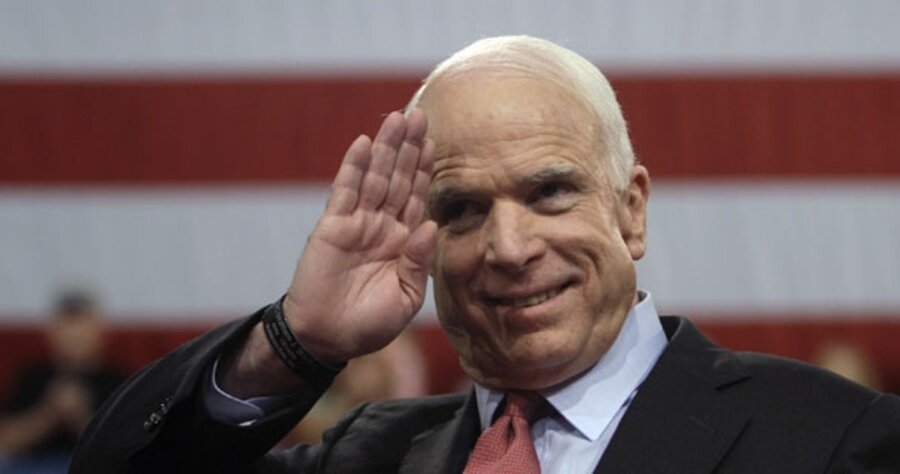

Portsmouth, Ohio - John McCain has made nuclear power a centerpiece of his energy plan. But at a town hall-style meeting in this struggling Appalachian city Wednesday, the first person he called on was a local woman in the corner with a hand-drawn "No Nukes" sign.

"Because of the interest of exchanging ideas and views that we may not agree with," Senator McCain said, striding toward her in the high school gymnasium, "I'll bring you a microphone, and you and I can have a little exchange and dialogue."

It's the kind of gesture seldom seen from McCain's Democratic rival, Barack Obama, a wizard of oratory who can rock a stadium but is less at ease in the sort of unscripted exchanges that are perhaps McCain's only rhetorical trump.

If the 2008 election is a study in contrasts, few are as striking as the candidates' differences as public speakers.

McCain is the blunt-spoken platoon leader, briefing soldiers for battle. Senator Obama is the evangelist, calling out from the hilltop. McCain levels. Obama transcends. McCain is straight talk, Obama great talk.

When Democrats announced this week that Obama would accept his party's nomination at a 75,000-seat football stadium – on the anniversary, no less, of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech – McCain advisers waved off questions about how Republicans would compete.

"John McCain isn't going to go into a stadium and talk to 70,000 people – you all know that," Carly Fiorina, the former Hewlett-Packard CEO who is one of his top advisers and a possible vice-presidential pick, said at a gathering for reporters in Washington this week. "It's not his," she said, pausing for a long moment before shrugging her shoulders, "personality."

Whether style matters is a subject of debate. But the times – rather than any axiom of politics – seem to dictate what sounds sweetest to voters' ears, analysts say.

William Jennings Bryan and Adlai Stevenson were star orators but never won the presidency. George H.W. Bush and Jimmy Carter were yawn-inducers at a lectern, but did.

An eloquent appeal to ideals like "hope" works best when voters want a crisp break from the past. When life is a daily struggle because of high gasoline prices and an unrelenting mortgage, they respond better to plain speech and nuts-and-bolts policy prescriptions.

When the times are a mix of both, voters can hear siren songs in each style of speech.

"The more flowery Obama gets, the less you trust him," says Jeanie Smith, a Portsmouth social worker who was a Hillary Rodham Clinton supporter and is now torn between Obama and McCain. Leaving the gymnasium here after McCain's visit Wednesday, she signaled approval of the Arizona senator's regular-guy banter. "Straight and direct," she said.

McCain excels at the give-and-take with voters in town meetings and other intimate settings, where his unvarnished musings and grasp of policy detail play well. As far back as 2000, he branded his campaign bus the Straight Talk Express because of the free-wheeling gab sessions with journalists aboard, a rarity in an age of heavily managed access to presidential candidates.

But in larger venues and in speeches, McCain's rhetorical style can sound like – as the Comedy Central host Stephen Colbert recently put it – "tired mayonnaise." His yen for the prefatory "my friends" can weary. His body language – a smile after sternly pledging to follow Osama bin Laden to "the gates of hell" – can seem incongruous and ill-timed. His jokes often sound recycled, and his tongue is prone to slips, as when he promised earlier this month to "veto every single beer" – instead of bill – "with earmarks."

As part of a campaign shake-up last week, McCain handed more authority to aides keen on punching up his messages and sharpening his stagecraft. But in his 20-minute speech in Portsmouth, before opening the floor to questions, McCain seemed to spend more time staring down at a set of notes on a waist-high music stand than he did making eye contact with the audience.

In his days at Harvard Law School, Obama listened to recordings of sermons and internalized the cadences of the black church, with their patterns of call and response and repetition of finely wrought phrases. The Illinois senator sprinkles speeches with "we" and "you" – "Yes we can" and "you have done what the cynics said we couldn't do" – as if he were as much guiding a movement as running for president.

It is a style well-suited to large venues but one that has faltered elsewhere. Senator Clinton, his former rival for the Democratic nomination, was generally viewed as the stronger debater, because of her command of policy minutiae and a better ability to seem resolute in the face of persistent questioning.

Obama's soaring oratory was also less successful than Clinton's more grounded policy specifics at connecting with working-class voters more worried about making ends meet than making history.

"With a lot of people in our state and in Ohio and West Virginia, there was this missing connection Obama had in the primaries that was palpable," says G. Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin & Marshall College, in Lancaster, Pa.

Both McCain and Obama belong to strains of political oratory that date to the country's founding, says Bruce Gronbeck, an expert on presidential rhetoric at the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

"Obama comes out of the more Puritan tradition – the vision of building a new Israel in the wilderness," he says. "McCain comes out of the Yankee tradition: Once we build a new world, we need practical folks who can help us face the environment, feed ourselves, produce an orderly government, and create a stable society."

If Obama's rhetorical forebears are Abraham Lincoln and Robert Kennedy, says Dr. Gronbeck, McCain's is perhaps Herbert Hoover, who called himself a "master of emergencies."

McCain, like Clinton, has raised questions about whether Obama is more style than substance. But the two are frequently inseparable in American politics, where voters as often act on gut as on a careful analysis of position papers, analysts say. In a USA Today/Gallup Poll last month, voters were slightly more likely to see McCain than they were Obama as a "strong and decisive leader" but far more likely to see Obama as in touch with the needs of ordinary people.

McCain might do well to acknowledge – or even poke fun at – his shortcomings as a speaker, while questioning whether Obama's rousing speeches are a smoke screen for inexperience, says Denise Bostdorff, an expert on political communication at the College of Wooster, in Ohio.

"You will have people who are immediately suspicious if someone is eloquent," she says.

Obama, however, has cast his oratory as an extension of his message. And if one measure is the number of new voters a candidate draws to the polls, Obama has been a runaway success.

"Don't tell me words don't matter," he said at a campaign stop in February, ticking off historymaking lines from speeches by Dr. King and Franklin Roosevelt. "It's true that speeches don't solve all problems, but what is also true is if we cannot inspire the country to believe again then it doesn't matter how many policies and plans we have."

One of the most anticipated moments in the four months till Election Day will be the candidates' first debate. But so far, there isn't one. With their different styles and strengths as speakers, they have been unable to agree on any.