Report says top officials set tone for detainee abuse

| Washington

Senior US officials, not rogue underlings, were responsible for the abusive treatment of detainees in US custody.

That’s the bottom line of a newly declassified, bipartisan report by the Senate Armed Services Committee released Tuesday night.

The report is likely to amplify growing calls among Democrats on Capitol Hill for an accounting of Bush-era abuses that includes top policymakers and the lawyers who advised them.

“The record established by the committee’s investigation shows that senior officials sought out information on, were aware of training in, and authorized the use of abusive interrogation techniques,” said Sen. Carl Levin (D) of Michigan, chairman of the Armed Services Committee, in a statement Tuesday night.

“Those senior officials bear significant responsibility for creating the legal and operational framework for the abuses,” he added.

Senator Levin has asked the Justice Department to launch a process “to establish accountability of high-level officials, including lawyers.”

The 18-month inquiry was approved unanimously by the Armed Services panel in November 2008, but it could not be released until vetted by the Pentagon. Some phrases and paragraphs in the 232-page report are still blacked out, but the panel is negotiating release of the remaining redacted material.

In a narrative that reads like a film script, the report documents how coercive methods used by Chinese communists to elicit false confessions from American POWs during the Korean War made it into interrogation rooms for detainees in US custody.

A key element was the redefining of the legal framework for the treatment of detainees after the 9/11 attacks. Drawing on more than 200,000 pages of classified and unclassified documents, the report tracks a legal paper trail and its consequences on the ground.

Policy changes came from the top and set a tone for the abuses on the ground that followed, the report concludes.

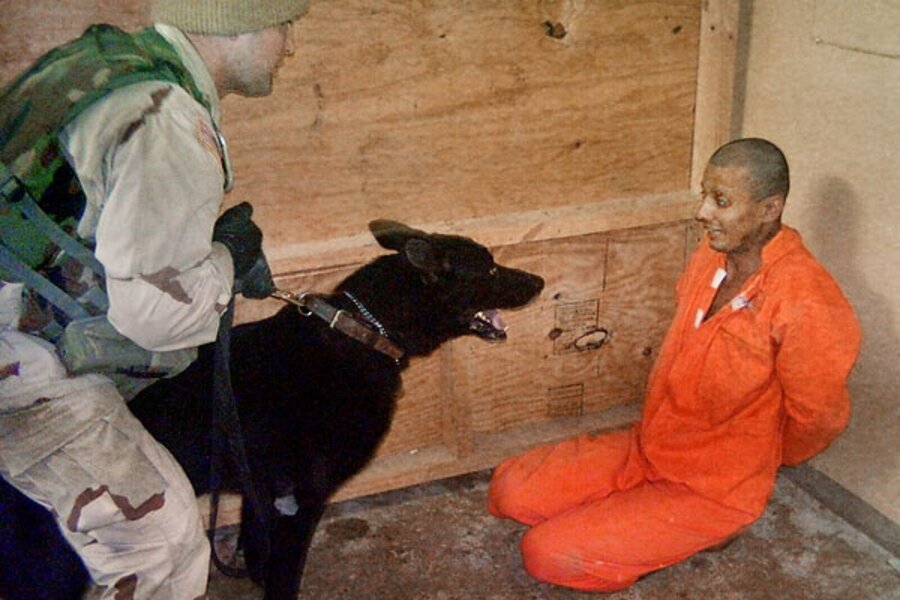

“Interrogation techniques such as stripping detainees of their clothes, placing them in stress positions, and using military working dogs to intimidate them appeared in Iraq only after they had been approved for use in Afghanistan and at GTMO [Guantánamo Bay],” the report said.

Standards became subjective

The narrative starts with President Bush’s Feb. 7, 2002, declaration that the Third Geneva Convention – which sets international standards for the treatment of POWs – did not apply to Al Qaeda or Taliban detainees. The statement included the caveat that the US armed forces shall “continue to treat detainees humanely and, to the extent appropriate and consistent with military necessity, in a manner consistent with the principles of the Geneva Convention.”

But interviewees said the standard was subjective and tough to apply in the field.

“The decision to replace well established military doctrine, i.e., legal compliance with the Geneva Conventions, with a policy subject to interpretation, impacted the treatment of detainees in US custody,” the report concludes.

High-level policy statements authorizing aggressive interrogation techniques and the influence of training techniques from the US military’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) program – banned on paper for use in US military interrogations but not in practice – also eroded standards of humane treatment.

“The use of techniques similar to those used in SERE resistance training – such as stripping students of their clothing, placing them in stress positions, putting hoods over their heads, and treating them like animals – was at odds with the commitment to humane treatment of detainees in US custody,” the report concludes.

Systemic abuse?

The report’s findings contrast with the Pentagon’s initial response to the gritty images coming out of Abu Ghraib in 2004, which was to blame the grunts. In a May 4, 2004, briefing, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz suggested that prisoner abuses by soldiers were only because of “a few bad apples.”

He added, “The people who were responsible will be held accountable, and if there’s anything systemic, it would be corrected.”

The Armed Services Committee report finds that there were in fact systemic abuses, and those responsible for them have yet to be sanctioned.

It’s a conclusion the Pentagon disputes.

“The Army field manual on interrogations is quite clear: It strictly prohibits the use of SERE techniques against individuals. They have never been authorized or approved for use against detainees,” says Navy Cmdr. Jeffrey Gordon, a Pentagon spokesman.

Since 2001, the Pentagon has conducted more than a dozen internal investigations into detainee mistreatment that have resulted in some 430 disciplinary actions, ranging from prison sentences and bad-conduct discharges to forfeiture of pay and allowances.

“All credible allegations of abuse were investigated and individuals are held accountable for their actions,” says Commander Gordon.

In fact, there is a lot of overlap between the conclusions in the congressional report and the 492 recommendations on detainee treatment produced by the investigations at the Pentagon.

But the Armed Services panel is calling for higher-level accountability. “The abuses of detainees at Abu Ghraib in late 2003 was not simply the result of a few soldiers acting on their own,” the report says.