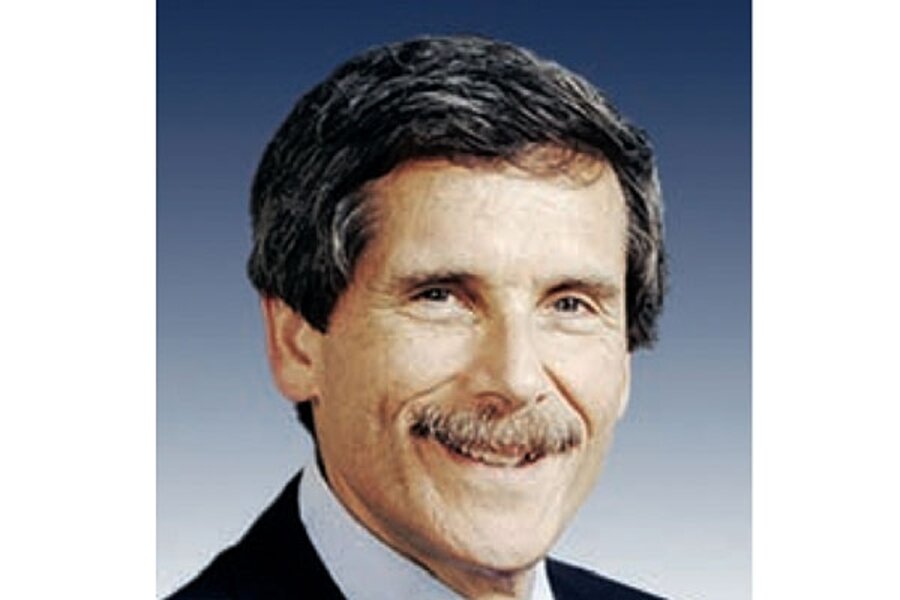

Who's Alan Frumin and why might he shape US health reform?

| Washington

With Sen. Olympia Snowe of Maine casting the first Republican vote for healthcare reform this week, Senate Democrats are upbeat that the goal of 60 votes to prevent a filibuster and get to a floor vote is within reach. But if the 60-vote strategy fails, Senate parliamentarian Alan Frumin suddenly becomes Washington’s top power broker.

Few people in Washington could pick him out of a lineup. (He’s the one whispering to the presiding officer.) But his rulings on Senate procedure can shape legislation more decisively than any lawmaker.

Master of Senate rules and precedent, the parliamentarian is also known for absolute discretion – and an aversion to publicity. Mr. Frumin, for one, rarely gives interviews and declined, through his office, requests to do so for this story. Nor would his office, tucked into a closed-to-the-public corridor in the US Capitol, release his biographical information.

“He’s a man who plays his cards very close to his vest, because he has to. Everyone is looking over his shoulder,” says Senate historian Donald Ritchie. “He’s very serious about what he does, and he’s scrupulously neutral.”

Here’s why he’s about to be in the spotlight: Once healthcare reform moves to the Senate floor, procedural challenges – which could gut the legislation – will be the first line of partisan combat. This will be especially true if Democrats move the bill to the floor on a fast track called reconciliation.

A simple majority vs. 60 votes

And it’s the parliamentarian who makes the call on which points of order are valid.

In the reconciliation route, major bills can pass the Senate with a simple majority, instead of the 60 votes needed for most major bills. But it also gives the minority powerful options to challenge any provision that does not contribute to reducing federal deficits. The parliamentarian’s rulings effectively decide what’s in or out of the legislation.

If it comes down to a procedural firefight, the bill could be carved up on the floor and wind up with more holes than “Swiss cheese” – a term now used by activists on both sides of the healthcare debate.

“Your guess is as good as mine what the parliamentarian will say. He is a god,” says R. Bruce Josten, top lobbyist for the US Chamber of Commerce.

Republicans say that having to rule on such key questions puts too much control in the hands of the parliamentarian.

“These can be very subjective calls. When the parliamentarian is called up to make them occasionally or rarely, the Senate accepts it. But several times a day, and it could really affect the credibility of the parliamentarian and hurt the office,” says Sen. Lamar Alexander (R) of Tennessee, who chairs the Senate Republican Conference. “To thrust him into the healthcare bill so he’s virtually writing the bill is unprecedented and unacceptable,” Senator Alexander adds.

It's hard to be Mr. Neutral

That was hardly the intent when the post of parliamentarian was created in 1937. Rather, the parliamentarian is to be a neutral, nonpartisan professional who serves the whole Senate, although at the pleasure of the majority leader. It can be a tough balance to get right.

Like the Senate chaplain, the parliamentarian does not rotate out with a shift in party control. So far, promotions have come from within the Senate parliamentarian’s office. Only a handful of people in the world know the Senate well enough to do the job.

Frumin, the current parliamentarian, grew up in New Rochelle, N.Y. He graduated from Colgate University in Hamilton, N.Y., with a double major in economics and political science, and Georgetown University’s Law School in Washington. His work as legal editor for the multivolume Deschler’s Precedents of the House of Representatives impressed the House parliamentarian, who recommended Frumin to the Senate parliamentarian.

Frumin “is an incredibly judicious, patient, bright man who has been given a job of enormous complexity and difficulty,” says Robert Dove, who worked with Frumin upon his arrival in 1977 until 2001.

In fact, Mr. Dove and Frumin have switched jobs three times. Frumin first became parliamentarian in 1987, replacing Dove after Democrats took over the Senate. When Republicans won back the majority, Dove was reappointed parliamentarian, and Frumin returned to the No. 2 job, with the title parliamentarian emeritus. He was reappointed parliamentarian in 2001, after Dove made some procedural calls that displeased then-majority leader Trent Lott (R).

“I was always a little bit concerned exactly who I worked for,” says Dove in a Monitor interview. “You do things in the name of the president of the Senate, who is the vice president of the United States. You conceive of yourself as working for the Senate – and Alan does. Not the majority party, but the Senate.”

War story from an ex-parliamentarian

In 1995, Dove made one of many tough calls, not unlike those Frumin is likely to face on healthcare. Republicans wanted to ban federal funding of abortions and use reconciliation to do it. Dove ruled against them. “In my view, that was not there to save money but to implement a huge social policy. It was knocked out of the bill,” Dove says, citing the so-called Byrd rule.

“But such calls are incredibly difficult, because you’re going into motive,” he adds. “It’s not just what a provision does, but why was it put there.”

His ruling did not please the majority, but that wasn’t his job. Like a good umpire, the parliamentarian must never be seen as favoring one side or the other or advising on strategy.

“You can never feed anyone information; you can never suggest questions that ought to be asked. You would destroy yourself quite quickly if you did,” Dove says. “All you can do is answer questions that are asked of you.”

Then he adds, “I’m so glad I’m not doing what Alan is doing right now. But he will do it well.”

----

Affordable medical care: how other countries do it.

As the US struggles to overhaul its system, nations from Taiwan to Germany offer a few lessons – and warnings.

----

Follow us on Twitter.