Does US need a second stimulus to create jobs?

Loading...

The economic stimulus package approved in February is the biggest recession-fighting effort in US history, but the question after nine months is whether it is big enough to bring back lost jobs. Money is rippling from the federal government throughout the economy at an accelerating pace. The $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act has allowed California's public schools to retain thousands of teachers, paid for contractors to repair dikes and levees on the Mississippi River, and employed workers who are installing new runway lights at Boston's Logan Airport, to name a few examples. It is financing nascent industries such as alternative energy even as it allots more money to address lingering problems like cleaning up hazardous waste at nuclear-weapons sites.

Yet the US economy remains in rough shape. The recession may be officially over, but Americans are still waiting to see that translate into job growth. Unemployment continues to creep upward, and has now reached 10.2 percent of the labor force.

That jobless rate has led critics to pan the stimulus as poorly designed, perhaps even useless. The Obama economic team, after all, had predicted early this year that the stimulus might cap the jobless rate at 8 percent. Instead, joblessness kept right on rising.

Stimulus supporters take a different view. The problem is not that it has failed, but that job-market woes proved to be deeper than many economists had expected. These economists say the answer is to stay the course – to spend the remaining $611 billion in stimulus funds. Some even call for a large additional boost in federal spending.

Congress is already moving at least modestly in this direction – although no one is calling it "stimulus." A measure to extend two stimulus elements that were set to expire – extralong unemployment benefits and a tax credit for homebuyers – was signed by President Obama Nov. 6. The measure also contains a tax break for money-losing businesses. The price tag of this new economic booster: just over $40 billion, far smaller than Mr. Obama's initial stimulus.

That's a hint of how the politics on this issue have changed of late. With the public more wary of new deficit spending, any fresh efforts to kick-start job creation are likely to be incremental rather than monumental.

This reflects the reality that Washington is attempting a delicate thread-the-needle strategy. The basic goal is for the government to spend prodigiously at a time of severe weakness in the private-sector economy, making up for part of the precipitous decline in consumer spending as households tighten their belts and work to shed debt. Then, when the private sector is ready to grow on its own, the federal role will decline, this reasoning goes.

One difficulty is that the government itself has a lot of debt, and stimulus spending only adds more. The US government can provide a cushion from recession. But it can't stop a larger force from playing out: The whole economy – from households to states to the US Treasury – faces pressure to live within its means after a period of unsustainable borrowing.

"That's an adjustment that needs to happen," says Enrique Mendoza, a University of Maryland economist who has studied the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus programs. "Consumption is going to be less. To that extent, [this adjustment] conflicts with what the fiscal expenditures are trying to do."

As he sees it, fiscal support has been effective and is still needed. It has helped to keep unemployment from being worse. Given the high jobless rate, he says, an extension of aid for the unemployed is warranted. But stimulus can't build the whole bridge back to a full-employment economy.

Simon Johnson, a former International Monetary Fund economist now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, takes a similar view of the challenge.

"With such countries that have ‘lived beyond their means' ... it is a mistake to try to prevent this process of competitive adjustment," he told a congressional panel last month. "The adjustment can be cushioned by fiscal policy.... But attempting to postpone adjustment with repeated fiscal stimulus is almost always a mistake."

Lawmakers know one thing, though: Voters want to see jobs. Unemployment could be a pivotal issue in 2010 elections.

On Nov. 6, Obama said his team is actively considering additional jobcreation efforts, from road-building to tax incentives and credit programs for businesses. The White House has planned a December jobs summit to explore ways to boost hiring by private firms. Moreover, by next spring, states will be considering their budgets for a new fiscal year, and deep job cuts are likely if the initial federal aid to states isn't expanded.

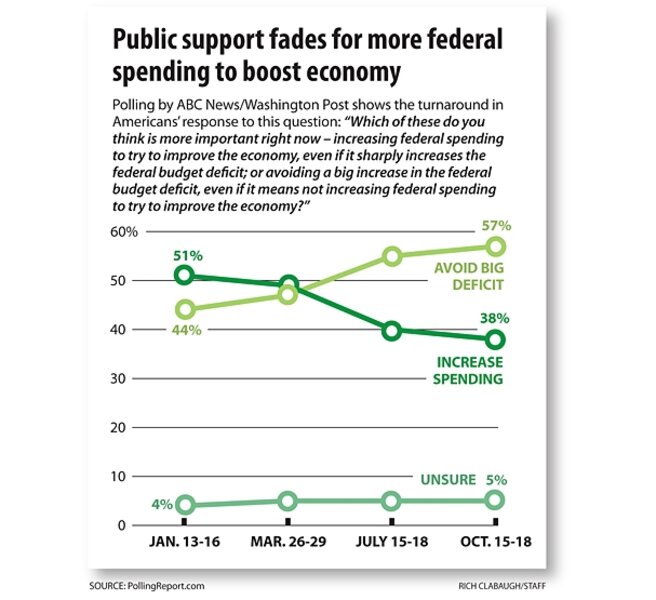

But politicians are squeezed the other way, too: Taxpayers are increasingly wary of any new stimulus programs with a big price tag, according to ABC News/Washington Post polls.

Early this year, as the Recovery Act was taking shape, most Americans supported federal spending to prop up the economy. Since then, the banking crisis has eased, and the economy has pulled out of a free-fall. Meanwhile, Congress's focus on health reform is drawing attention to the prospect that taxes may go up in coming years. The poll now finds Americans tipped against new stimulus spending.

Thus, some in Congress may take a wait-and-see approach. The bulk of Obama's original recovery program has not yet been spent – and is slated to roll out over the next 12 months. Lawmakers are hearing mixed views from economists, not the pro-stimulus consensus that existed earlier this year.

Where the jobless rate heads from here is likely to determine the mood on Main Street and Capitol Hill. Some groups already face particular stress. Unemployment is more than 15 percent for African-Americans, people ages 20 to 24, and workers in Michigan, for example.

What has the massive stimulus achieved so far? Here's an overview, based on data tracked by private-sector economist Mark Zandi:

• Some $50 billion, or nearly one-third of Recovery Act spending so far, has gone to safety-net programs and to one-time payments to Social Security recipients. The programs, including extended unemployment insurance benefits and food stamps, are not only compassionate but also effective at boosting consumer spending, says Mr. Zandi of Moody's Economy.com in West Chester, Pa.

• About $59 billion has gone to tax cuts, affecting most workers and many businesses. The tax-cut virtue is that it affects pocketbooks quickly. A potential problem is that when people get the cash, many also get the feeling they're eventually going to pay for that cash in higher future taxes.

• More than $50 billion in transfers to state and local governments has helped avert sharper budget cuts there. As many as 350,000 teacher jobs may have been saved, the Obama administration reported recently. Much of this state aid money flows through to the private sector, such as to hospitals (most of the state aid goes to support Medicaid).

• Only $14.4 billion has been paid out so far in direct federal spending on infrastructure and other projects. If the projects are socially useful, these investments can provide some of the strongest positive ripple effects for the economy, Zandi and others say. The bad news is they take time to get off the ground.

Speaking to Congress recently, Zandi said the high jobless rate is not a signal that the stimulus is failing. "If anything, it suggests the $787 billion stimulus was too small," he said. He elaborated in a recent conference call with reporters, arguing that another $100 billion or so in stimulus spending could help ensure that the economy doesn't relapse into recession next year.

Stimulus advocates note that the pace of job losses has slowed sharply this year, and say it's no accident that economic growth has turned positive just as the stimulus ramped up.

The White House estimates that 1 million Americans now have jobs that wouldn't exist without the stimulus, and that the total will reach 3.5 million next year before fading as the stimulus runs out.

Skeptics say the stimulus has not lived up to expectations.

"Where are the jobs?" has become a refrain among Republican leaders in Congress, citing the still-downward path of US employment. Critics also say the Obama administration is working against its own efforts, with other policies that hinder a jobs recovery. Examples include prospects of new healthcare mandates on employers and rising energy costs under a "cap and trade" plan for carbon emissions.

News reports, meanwhile, have poked holes in data on stimulus-related jobs, recently posted on the White House's www.recovery.gov website.

Both sides agree on one thing: The stimulus isn't nearly filling the recessionary hole in jobs or gross domestic product (GDP). Some 7 million jobs have disappeared since December 2007.

One private forecasting firm, IHS Global Insight in Lexington, Mass., estimates that the stimulus is saving jobs, but on a smaller scale than White House numbers: about 900,000 jobs saved this year, and probably 2.5 million by the end of next year.

"The question mark is whether the private sector is ready to take over the recovery," says Nigel Gault, Global Insight's chief US economist.

Many economists expect the private sector to start creating more jobs than it eliminates next year. If the pace isn't strong enough to bring down unemployment, Congress will at least consider more stimulus.

Rising government debt is a reminder, though: Stimulus is not a free lunch. Eventually it must be paid for.