History shows “coattail” effect not so crucial to presidents

| Washington

The trifecta of national politics is for a candidate to win the White House and help his party win control of Congress on presidential "coattails."

But is it "game over" for a president when the other team controls the House, the Senate, or both? Not necessarily. Turns out, presidents don't always get what they want when their party has a majority on Capitol Hill – or fail, when that majority is lost. Moreover, divided government can be the mother of legislative invention, forcing presidents to find common ground with a hostile Congress, if they can.

Past presidencies offer hints for dealing with a Congress of a different persuasion.

Numbers on 'our side' do not equal control

President Dwight Eisenhower, the World War II hero, was swept into office winning all but nine states and helping Republicans take control of the House and Senate on his coattails.

But rather than line up behind the new president, the GOP majority attacked his nominees, his legislative priorities on defense spending, and his presidential powers in foreign policy.

When Democrats won back control of the House and Senate in 1954 – and kept it through the Eisenhower administration – "it was a blessing in disguise," wrote Eisenhower biographer Jean Edward Smith. In short, Eisenhower made a tactical shift to the Democrats. Born in Texas, he developed close relations with House Speaker Sam Rayburn and Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson. The "three Texans" met weekly in joint strategy sessions that produced the Interstate Highway System and the St. Lawrence Seaway, expanded Social Security, raised the minimum wage, and established the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

President Jimmy Carter (D) – a former Georgia governor who campaigned as a Washington "outsider" and tried to govern that way, too – never established a working relationship with the Democrat-controlled Congress. Lawmakers complained that he lectured them and piled on more priorities than could be handled. Carter's agenda barely registered on Capitol Hill.

Divided party control of Congress is not fatal

President Ronald Reagan's 1980 election helped put Republicans in power in the Senate for the first time since 1953, but he never had a unified GOP majority in Congress to back his agenda. Reagan did not push the GOP's social agenda. Instead, he worked with some 40 conservative Democrats, such as then-Rep. Phil Gramm (D) of Texas, a member of the House Budget Committee who became a virtual surrogate for Reagan's "supply side" tax cuts and other economic proposals.

President Richard Nixon never had a Republican majority in either house. But he needed a legislative record to run on and made broad overtures to Democrats on issues ranging from welfare reform to a national health insurance partnership. Sen. Edward Kennedy (D) would later write that his biggest mistake in Congress was not taking Nixon up on this offer to work toward comprehensive health-care reform.

To the dismay of GOP conservatives, Nixon significantly boosted funding for Social Security and established new regulations to protect consumers and the environment, including signing into law the Occupational Safety and Health Act (1970) and establishing the Environmental Protection Agency, before Congress could act, by executive order. He resigned, under threat of impeachment over the Watergate scandal, in 1974.

Big defeats can force midcourse corrections ...

President Bill Clinton launched his presidency with a bid for health-care reform, worked out behind closed doors by Hillary Rodham Clinton and blue-ribbon advisers. Big Democratic majorities in Congress, not included in the deliberations, balked, and the plan died. But after a historic GOP sweep in midterm elections, Democrats lost control of Congress, and House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R) of Georgia declared Mr. Clinton irrelevant. Clinton fought House Republicans through two government shutdowns over budget deficits – an impasse that the public blamed on House Republicans.

Clinton adapted: He worked with House Republicans to produce four balanced budgets and, over objections of many Democrats, signed a GOP welfare reform bill in August 1996 similar to two he'd vetoed previously. Clinton was later impeached by the House (but not convicted by the Senate) on charges related to the Whitewater and Monica Lewinsky investigations. Still, his popularity soared.

... or not

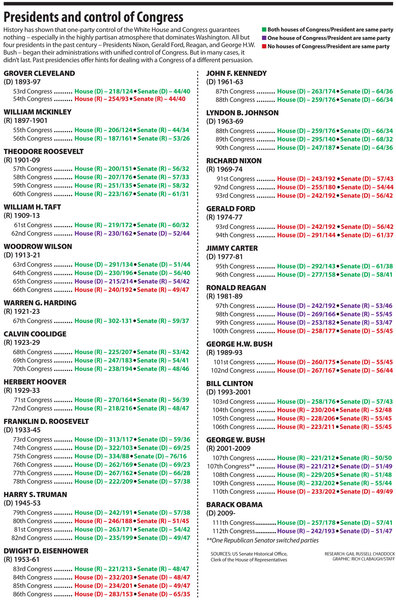

All but four presidents in the past century – Presidents Nixon, Gerald Ford, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush – began their administrations with unified control of Congress. But in many cases, it didn't last.

President George W. Bush started with a unified GOP government, lost it after a GOP senator defected in 2001, regained it in midterm elections after 9/11, then lost both houses in 2006 midterm elections. Burdened by the nation's wars and bitter partisan divisions, Mr. Bush did not change course – and ended his administration with dismal public approval ratings.

After a euphoric win in 2008, President Obama pushed his health-care reform through a Democrat-controlled Congress without a single Republican vote. Facing a backlash over the unpopular health-care law, Democrats lost control of the House in 2010. The failure of the president and the new House GOP majority to come to terms on debt and deficit issues brought the nation to the brink of default.

QUIZ YOURSELF: So you think you know Congress?

But should Mr. Obama win a second term and face a GOP-controlled Congress, he may not have the Clinton or Eisenhower options to fall back on, analysts say. In a break with recent history, parties no longer have a core of centrists to help broker bipartisan compromises.

"Since the 1960s, the number of members in Congress who vote as centrists is vanishing," says Julian Zelizer, a congressional historian at Princeton University. "I'm not sure the Clinton model or Eisenhower model is possible for Obama now. Republicans will remain fierce opponents of everything he wants."