Is the tea party running out of steam?

Loading...

| Olive Branch, Miss.

Tea party challenger Chris McDaniel might have felt discouraged when he walked into a recent Reagan Day Dinner here in northern Mississippi.

After all, many people were wearing "Thad" stickers. Six-term Republican Sen. Thad Cochran is such a fixture in the state that his unusual first name alone is enough to send the message: He’s the favorite of establishment Republican activists in Mississippi's June 3 primary.

But state Senator McDaniel, arguably the top tea party hopeful nationally in the 2014 cycle, is undaunted. He quietly works the room and even wins a recruit – a college student, who agrees to organize for him.

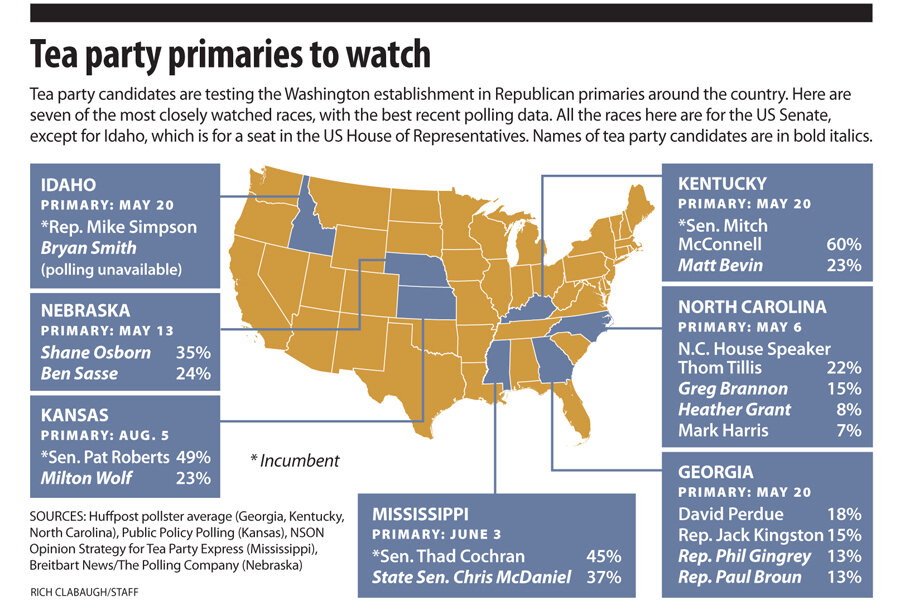

Maybe it's Southern good manners or the name of the town – Olive Branch, Miss. – that gives the event such a harmonious vibe. But in fact, McDaniel versus Cochran is the hottest Republican primary of the 2014 midterms. Other tea party challenges to incumbent GOP senators have faded, turning Mississippi into a proxy for the national battle between establishment and tea party Republicans.

Now McDaniel may be heading for trouble, too. This week, an old audio clip from his days as a talk-radio host surfaced, with him making provocative comments about women, Mexicans, and reparations for the descendants of slaves.

The story made waves in the national media, less so in local media. The impact, so far, could be more with the Washington-based groups that are backing McDaniel, rather than with Mississippi voters. The McDaniel campaign dismissed the recording, which was given to The Wall Street Journal, as "decade-old comments made on conservative talk radio."

Fairly or not, the outcome in Mississippi's primary will shape public views of the tea party nationally. If McDaniel beats Senator Cochran, it will be the third election cycle in a row in which a veteran Republican senator loses to a tea party upstart. The headline will read: "GOP establishment fails again to tame unruly hard-liners." If McDaniel loses, claims that "the tea party is fading" will only grow.

But five years after the movement burst onto the national scene, its reality is more complicated. Defying the GOP establishment, tea party muscle has sent some of this era's most charismatic Republican politicians to Washington, starting with Sens. Rand Paul of Kentucky and Ted Cruz of Texas. They have changed the debate in Washington, polarized their own party, and sharpened gridlock. House Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio and the tea party are openly at war.

Regardless of what happens in the primaries and in November, the tea party will live on.

"The tea party's hold on the GOP persists beyond each burial ceremony," writes Harvard sociologist and political scientist Theda Skocpol in The Atlantic.

That's in large part because tea partyers themselves aren't going away. Even as Gallup polls consistently find the percentage of public support for the tea party mired in the low 20s, determination among activists not to compromise on matters of principle has only grown. After the Republican failures of the 2012 election – including two botched GOP chances to pick up Senate seats – an academic survey found members of the tea party group FreedomWorks to be more "purist" than before the election.

In December 2011, one-third of respondents strongly agreed that "we should not be willing to compromise with political opponents when we feel strongly about political issues." By spring 2013, that figure had grown to nearly half.

"You might think that having lost in 2012, tea party Republicans would soften a little. But no," says Ron Rapoport, a professor at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Va., who conducted the survey. "There's real polarization within the Republican Party, and the gap is growing."

The evolution of a movement

At the grass roots, the tea party is still fueled by anger: Government is still too big, federal debt is ever-rising, the Constitution is in tatters. "Obamacare" has poured gasoline on the fire. But the protests have largely moved from the streets to the electoral arena and the halls of government. In 2011, tea party involvement in congressional redistricting helped lock in GOP control of the House.

In a bit of an oxymoron, a "tea party establishment" has taken shape, with sophisticated fundraising. Some, like Tea Party Patriots – an umbrella group with more than 2,000 local chapters – are new. Most, like FreedomWorks, Club for Growth, and the Senate Conservatives Fund, predate the tea party but helped it launch as an electoral phenomenon and are now major patrons. FreedomWorks for America, a "super political-action committee," helps local activists. Club for Growth and the Senate Conservatives Fund back candidates with television and radio ads through their super PACs.

All are taking on Republicans deemed not conservative enough. At times, the differences between establishment and tea party can be more style than substance. To establishment Republicans, a vote to end the government shutdown last October was a pragmatic acknowledgment that the effort to defund Obamacare had hit a dead end. But to many tea partyers, with Senator Cruz leading the charge, the vote signaled a betrayal of principle.

"There was no son of Mississippi in the room, and there should have been," McDaniel says in a Monitor interview.

On the stump, McDaniel makes Cochran out to be a supporter of Obamacare, because the senator voted to reopen the government with a resolution that included funds for the reform. (A Cochran ad says he has voted against Obama-care more than 100 times.) McDaniel also slams Cochran for voting to raise the debt ceiling "more times than I can count," and is generally critical of Cochran's low-key style.

"He's not a vocal enough opponent of the Obama administration," says McDaniel, a six-year state legislator and trial lawyer. "People of this state can't name a single fight he's engaged in against Barack Obama."

The 'pork' problem

For Cochran, 41 years of service in Washington haven't been about making noise; they've been about taking care of Mississippi – its farmers, its military bases, its flood-prone areas, and most dramatically, its rebuilding after hurricane Katrina in 2005.

McDaniel stumbled in a Politico interview in February when asked about federal disaster relief after Katrina, saying he "probably would have supported it," but would need to read the bill. A major gaffe, say Cochran supporters. In Mississippi, Katrina aid is sacred.

Tea party leaders here defend McDaniel, saying it's correct to question whether disaster relief is laden with unrelated spending and lacking in oversight. But the topic goes to the larger issue of federal funds coming to Mississippi – a state that receives far more money from Washington than it sends in taxes, without apology.

"Mississippians are perfectly happy to take federal dollars, in almost any form," says Joseph Parker, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg.

It is a time-honored tradition in Mississippi to send senators to Washington to bring home the bacon, and stay well into old age. McDaniel doesn't say that Cochran is too old, just that it's time for "new ideas." In his announcement video, McDaniel called Mississippi a "welfare state." Mississippi, after all, is the poorest state in the nation, by many measures. But when asked if he has a plan to wean his state away from federal money, he demurs.

"Bear in mind, the federal government does some things very well," the state senator says. "Mississippi is a strong military state. We need that military spending."

But earmarks, or "pork," are another matter. "It's a quid pro quo," McDaniel says. "To the extent that they build a new post office here, Senator Cochran votes for a 'bridge to nowhere' in Alaska."

Tea party leaders here believe Mississippians are fed up with "out of control" federal spending and debt. But the goal shouldn't be to reduce funding just to Mississippi – it's "to restore the constitutional balance that was created between the federal government and the states, and who's responsible for what," says Roy Nicholson, former chairman of the Mississippi Tea Party.

Welfare, health, education, pollution, roads – those are matters "specifically reserved for the states," he says. Mr. Nicholson believes McDaniel is "truly convinced" of the wisdom of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and has earned his support.

To Laura Van Overschelde, current chairwoman of the Mississippi Tea Party, the message of personal responsibility is central. “Never let a man become comfortable in his poverty,” she says, paraphrasing Benjamin Franklin.

“We have lost that concept that everyone who is an adult and able-bodied has some personal responsibility for his wherewithal,” Ms. Van Overschelde says.

Tea party energy has fueled McDaniel’s campaign. Tea party activists have been walking neighborhoods around the state on his behalf for more than a month. FreedomWorks is helping with yard signs, door hangers, and phone banks.

Establishment strikes back

Tea party energy makes Cochranites nervous. Though polls show the senator with a high-single-digit lead, the key is who turns out. One establishment figure, state Republican National Committeeman Henry Barbour, cofounded Mississippi Conservatives, a pro-Cochran super PAC, in January. It's getting fundraising help from his uncle, former governor and national party chair Haley Barbour. The group is running TV and radio ads.

In an interview, Henry Barbour says Mississippi Republicans hadn't experienced the divisions of other state parties – until now. And he's frustrated by outside groups from Washington trying, as he sees it, to divide conservatives in Mississippi for their own political gain.

"My view is, Club for Growth has got to go get a scalp from somebody so they can raise money next year," Mr. Barbour says.

Still, Barbour acknowledges that tea partyers are a force. He estimates they make up about a third of the state GOP electorate, and so McDaniel would need another 15 percent of "regular Republicans" to win.

If McDaniel pulls it off, Barbour says, it's a 50-50 race in the general election against likely Democratic nominee Travis Childers, a former congressman. If Mr. Childers were to win, that would set back Republicans' drive to retake the Senate.

McDaniel rejects the idea that he could cost his party the seat. Mississippi is solid red, end of story. And after the stumbles of past GOP Senate candidates – remember Todd "legitimate rape" Akin of Missouri? – McDaniel is on notice to watch his words and actions. Though he hadn’t counted on that old radio recording coming back to haunt him.

In Kentucky, Matt Bevin, the tea party-backed challenger to Republican Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, recently spoke at a rally to support cockfighting, which is illegal. Mr. Bevin called his participation a misunderstanding – it was a "states' rights rally," his campaign said – but the damage was done. Bevin's already-struggling campaign is sinking further.

Other tea party challenges to incumbent senators have either already failed (Texas) or are in trouble. Physician Milton Wolf's threat to Sen. Pat Roberts (R) in Kansas suffered a blow in February when he was found to have posted graphic X-ray images to his Facebook page in 2010. Dr. Wolf apologized.

McDaniel skirted controversy in early April after his name appeared on a flier for a Firearm Freedom Day event in May that included a vendor selling "white pride" merchandise. McDaniel's campaign says he never agreed to go. His name was removed from the flier, as was the vendor's.

But the episode – and the more recent surfacing of the old radio comments – threatened to revive discussion of race and the tea party. Charges of racism, centered in "birtherism" and a rejection of President Obama's legitimacy, have dogged the movement from its start. As the tea party becomes entrenched as a wing of the Republican Party, any image problems become the GOP's problem.

The Republican establishment has been fighting back. Last November in the primary for a special House election in Alabama, mainstream favorite Republican Bradley Byrne beat a tea partyer who said Obama was born in Kenya. The US Chamber of Commerce, outside groups, and GOP congressional leaders supported Mr. Byrne with a flood of money and ads. Byrne won the primary, but only by five points.

What the tea party has learned

National tea party organizations sat out the race – a sign they are learning as well. The movement's first lesson was better vetting of candidates. Just because they call themselves "tea party" doesn't mean they deserve a national group's investment, movement leaders say.

"There's been a growing sophistication of the movement," says Matt Kibbe, president of FreedomWorks. "We realized we had to start from the bottom up."

That has meant building a farm team: people who serve first on school boards, on county commissions, and in state legislatures before trying for higher office. The strategy may be working in Texas, where two tea party state legislators are running strongly for lieutenant governor and attorney general.

"To some extent, the movement has refined itself," says Drew Ryun, political director of the Madison Project, a tea party super PAC that has endorsed McDaniel. "It's become more mature in how it engages in politics."

It has also moved beyond just winning elections toward holding elected officials accountable, he says. Now that both houses of Congress have high-profile tea party caucuses, movement leaders are under growing pressure to show results and prove that the tea party is not losing steam. At a recent conference of the Tea Party Patriots, Sen. Mike Lee (R) of Utah called on activists to form a new agenda that can unite party leaders and grass-roots activists.

The call for ideas was striking. Just five years earlier, the tea party knew exactly what it was about – lower taxes, less regulation, and smaller government. But as its leaders say, the time for protests has passed. Tea party factions have sprung up.

Some avoid the term "tea party," which may reflect in part its poor public image, but also a desire for different emphases. Some activists prefer "liberty movement," for its libertarian approach. Others favor "constitutional conservatives."

"This is a complex, beautifully chaotic movement," says Mr. Kibbe of FreedomWorks.

Some analysts liken the tea party to the antiwar movement of the 1960s. It began as a protest movement and later became a faction within the Democratic Party.

"It was fairly purist on the war, and it cost [Hubert] Humphrey the election in 1968. Then in '72, it got its guy, George McGovern, and he got clobbered," says Mr. Rapoport of William & Mary.

In effect, the antiwar movement had its shot, and then faded away.

"I don't feel the tea party thinks it's had its shot," Rapoport says.