Why billionaire's low tax rate isn't a big deal in Illinois governor's race

| Chicago

One candidate is accused of channeling personal investments through the Cayman Islands to avoid US taxes. The other candidate is accused of participating in a pension fund that relies on the same kinds of offshore investments.

Welcome to the Illinois governor’s race, where the personal wealth of candidates is under fire – but may not as matter as much as it used to in recent years.

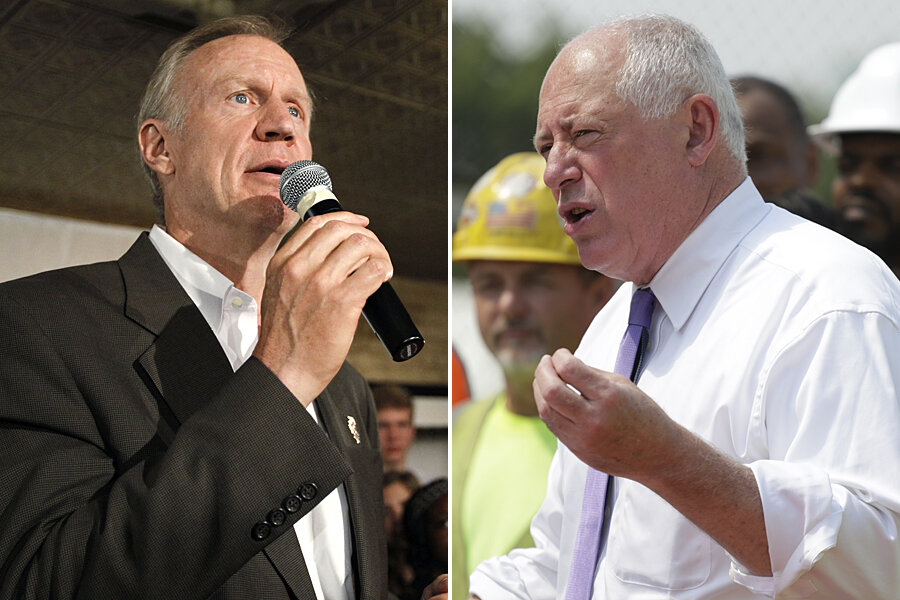

According to local media reports, Republican candidate Bruce Rauner, a billionaire equity investor from Chicago’s northern suburbs, for years paid taxes on the majority of his millions in annual earnings at 15 percent, a rate less than half the top federal rate for the wealthy.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings show that his offshore ties are connected to a Chicago private equity firm where he worked before his gubernatorial bid. At first Mr. Rauner said he was not aware the firm had offshore investments; last week he told the Chicago Tribune the firm goes overseas for “just a couple of investments.”

He has refused to release documents aside from the basic tax filings that are required under state law.

“We’re not competing to become CEO of a corporation, we’re competing for the governorship of the state of Illinois.… This is a public office that requires public disclosure,” Paul Vallas, running mate for Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn (D), told reporters this weekend.

Governor Quinn has exploited the reports, which have added to his portrayal of Rauner as an out-of-touch oligarch. On Monday, he released a television ad that uses the recent headlines against “America the Beautiful,” followed by a tagline: ‘Did Bruce Rauner really think no one would find out?”

Quinn, however, who has been governor since 2009, could not escape his own association with the Cayman Islands. Rauner went on the counter-offensive last week, saying the governor’s state pension fund invests in the offshore tax haven. He called on Quinn to apologize and divest all state investments from overseas companies and funds.

The retirement fund for Illinois teachers invested $433.5 million in the Cayman Islands, while the state retirement fund, which includes Quinn’s pension, has invested $2.3 billion offshore. Neither retirement fund directly benefits individual investors, according to the Chicago Sun-Times.

Two years ago, similar charges were brought against Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, also a wealthy equity investor. Democrats successfully played on Romney’s investment in foreign tax havens like the Cayman Islands – and his use of other financial devices that allowed him to pay a lower capital gains rate on his income – to create the perception that he was out of touch with the economic struggles of everyday Americans.

Mary Ellen Balchunis, a political scientist at La Salle University in Philadelphia, says that the portrayal of being wealthy and avoiding taxes remains a potent one in general elections, especially on the heels of a recession that wiped out the savings and investment holdings of many middle-class Americans. “Yesterday, the electorate might not have paid attention to where their elected officials are hiding their money to avoid taxes, but today, it could make the difference in a close election,” Professor Balchunis says.

Yet other issues in the Illinois race may divert the scrutiny of the tax issue: The Democrats are being blamed for rising property taxes, continual budget problems, and an unfunded pension crisis that has so far defied solution.

For the time being, Rauner appears shielded from the criticism of his investments. According to a Chicago Sun-Times poll released Sunday, Rauner is beating Quinn, 51 to 38 percent, with 11 percent undecided. Moreover, Most Illinois voters consider Rauner the reform candidate by 47 percent, while only 22 percent give that designation to Quinn. About 17 percent say neither.

“Rauner’s claim to ‘shake up Springfield’ may be resonating with voters.… Plus, it’s hard for a public official who has been around as long as Governor Quinn to wear the reform hat when he’s been part of the system so long,” says Gregg Durham, chief operating officer of We Ask America, which conducted the polling for the newspaper.

Because Illinois is in such dire straights financially, “the net overall effect of Rauner’s wealth is sort of a zero – it cancels out,” says Andrew McFarland, a political scientist at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

“While it is true the majority of Illinois voters may see Rauner as “a financial manipulator,” Professor McFarland says, Quinn’s record is not strong enough to offer any kind of potent alternative to fixing the state’s financial crisis.

“Most people think [Quinn’s] a good-hearted person, but there’s a lot of people feeling we need something different,” he says. “And, of course, Rauner took over that narrative.”