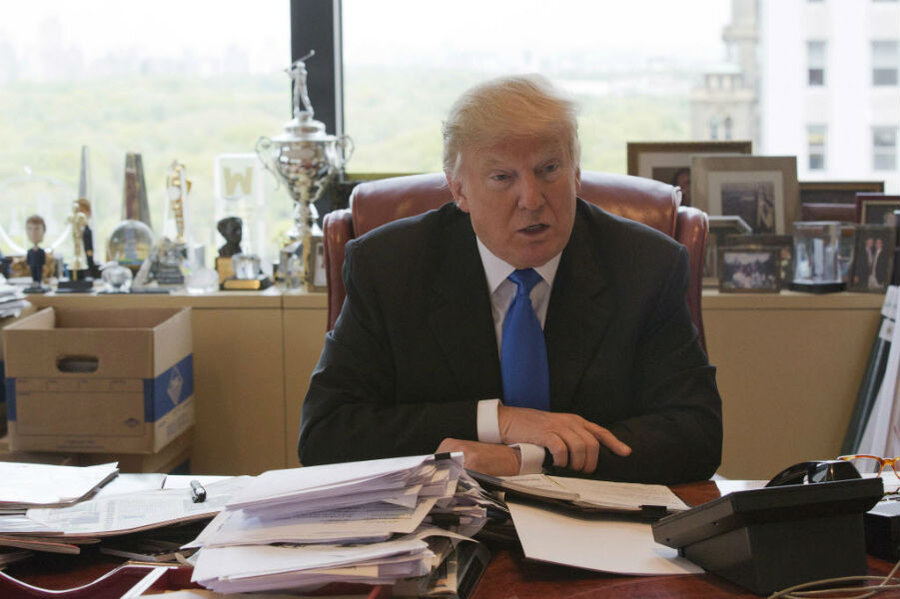

Could Donald Trump run his company and the country?

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump said Thursday if he is elected president, he will avoid conflicts of interest between his company and the country by relegating business obligations to his children while governing the nation.

"Well I will sever connections and I'll have my children and my executives run the company," Mr. Trump told "Fox & Friends" in a telephone interview Thursday morning. "And I won't discuss it with them. It's just so unimportant compared to what we're doing about making America great again. I just wouldn't care."

But many wonder if that separation would be enough to ensure his presidency isn't tainted by other ventures.

The question of how Trump would balance competing loyalties between his real estate empire and his country comes after a Newsweek exposé of Trump's foreign business ties blasted the real estate mogul Wednesday, arguing that there was no ethical way Trump could maintain the various enterprises he's built around the world and live in the White House.

"Never before has an American candidate for president had so many financial ties with American allies and enemies, and never before has a business posed such a threat to the United States," Kurt Eichenwald wrote in the Newsweek piece. "If Donald Trump wins this election and his company is not immediately shut down or forever severed from the Trump family, the foreign policy of the United States of America could well be for sale."

Forbes has estimated Trump's networth to be around $4.5 billion. Internationally, that includes four golf courses abroad and buildings in Brazil, Canada, India, Uruguay, Panama, the Philippines, Turkey, and South Korea, according to his real estate portfolio.

Blind trusts are a common tool used by elected officials to host their assets and avoid conflicts of interest, and nearly every president since Lyndon B. Johnson has put his business interests in the hands of such an administrator who keeps the owner in the dark. New Jersey governor Chris Christie uses one himself, and told MSNBC he adopted this approach upon taking office seven years ago and has no idea where his investments stand.

But if Trump puts his wealth and enterprises under the control of his children, is that same as a blind trust?

"I think, listen, the father and the children have a lot of things to talk about other than the business," Governor Christie said. "They have grandchildren, many of them. He's involved in every aspect of their life and they in his. And I think that these are professional smart people who will, as we we can see with his tax returns, follow the advice of their lawyers and their accountants."

The scenario Trump has proposed may not be so blind after all. Because he would place his children in charge of the very public company, some wonder just how much of their business decisions would be kept from Trump.

"There a lot of reasons not to have a blind trust," Richard Painter, a law professor at the University of Minnesota, tells The Christian Science Monitor. "I don't really see how blind this could be with a real estate empire."

Past officials have put their assets into blind trusts and allowed an investor to sell them and reinvest the funds in something else. Because Trump's real estate company is a public one he intends to retain, its successes or failures would often be apparent to him.

While failing to separate business and politics could put the US at risk, there are no legal ramifications for neglecting to do so, as the US criminal conflict of interest statute doesn't apply to the presidency. But there could be severe political ramifications if Trump was caught using his power as president to boost his business ventures.

Conversely, Trump's political stance has already shown its ability to adversely affect him abroad. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan called for the Republican nominee's name to be removed from a tower in Istanbul following outcry over Trump's anti-Muslim rhetoric.

In January, before the British parliament debated whether to ban him from the country, Trump threatened to withdraw $1 billion of planned investment in his Scottish golf courses if the members of parliament voted to ban him. They didn't.

Despite years of precedent set by former leaders, Trump is legally allowed to maintain control over both the US presidency and his business empire. What he can't do under US law, however, is accept large "gifts" from foreign governments, a conflict that could occur if his business were to directly benefit from the actions of another nation.

"A bottle of vodka from Vladimir Putin, that's fine," Mr. Painter says. "The problem is if you have a company doing business with company run by foreign governments, each one of those transactions could be looked as if there’s a gift in it."

So, if Trump's name were to appear on a building constructed by a government-owned building abroad, he could face legal repercussions.

Painter said the best way for Trump to avoid the influence of his real estate empire would be to sell all of it, but such a decision seems unlikely for a man who has spent his career putting his name on nearly everything he builds.

"He feels he doesn't have to do it," Painter suggests.