When would Clinton, Trump use nukes? Why voters aren't asking.

Loading...

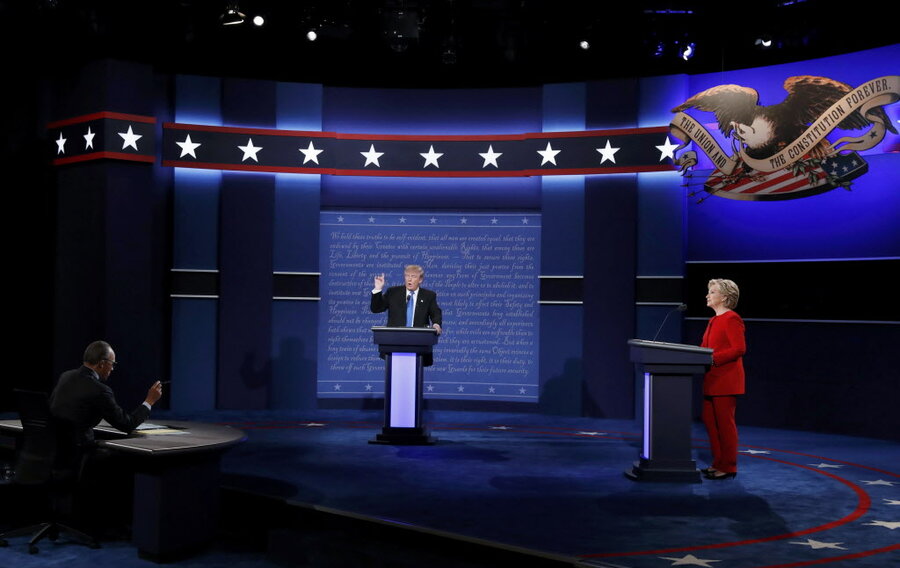

Donald Trump seemed confused by the question on nuclear weapons. In the Sept. 26 presidential debate, moderator Lester Holt asked the GOP nominee whether he would consider "changing the nation’s longstanding policy on first use," which leaves open whether the United States would initiate use of nukes in a conflict.

Mr. Trump circled the issue with care, as if it were a hissing snake. He said he would "certainly not do first strike," but added that, "I can't take anything off the table" – an obvious contradiction. Then he retreated with a quick riff on China, North Korea, and the perfidy of the Obama administration’s Iran nuclear deal.

Hillary Clinton didn’t answer the question, either. Given a chance to reply, she pivoted to another issue. "Words matter when you run for president," she said, adding that she wanted to reassure allies that Washington's word was good and the US would stand by defense pacts, despite Trump's musings to the contrary. She all but said, "Why yes, Lester, I was secretary of State. Thanks so much for asking!"

Again, Mrs. Clinton did not actually use the words in that last sentence. But the entire exchange, about a crucial aspect of national security that the Obama administration has weighed whether or not to change, was unedifying in the extreme.

As the second presidential debate of 2016 approaches Sunday, it's a reminder that important issues of defense and foreign policy are often addressed only vaguely, if at all, during White House campaigns.

"The absence of relevant information elicited by Lester Holt's excellent question speaks directly to what has become a central flaw in this entire presidential campaign: the dearth of attention given to matters basic to US national security policy," writes Andrew Bacevich, a Boston University historian and retired US Army colonel, in a recent opinion piece on the subject.

A lack of detail

That lack of attention is obvious after a quick run-through of the issue section of both candidates' web pages.

Trump's foreign policy and defense information is sketchy, at best. The former is almost entirely about the Obama administration’s inability to crush the Islamic State. The latter is a short recitation of pledges to increase the size of the overall US armed forces.

Clinton devotes more space to such issues. But again, much of the content is exclamatory, with sections titled, "Ensure we are stronger at home" and "Stick with our allies." Terrorism is perhaps one exception. Clinton lays out a moderately detailed multipoint plan for combating ISIS that includes increased support for local Arab and Kurdish groups and intensifying the coalition air campaign.

(Trump has said that as president he will sit down with top generals and devise a plan to fight ISIS, which he won't reveal in advance.)

Of course, terrorism – and by implication the defeat of ISIS – ranks as the most important defense and foreign policy issue in the minds of voters. Polls have consistently placed it second or third on most voters' priority lists over the course of the past several years.

But the economy and jobs has long topped that most-important-issue list, and by a wide margin. With rare exceptions, that's the way it's been for decades. Geopolitics is not something that sways most presidential elections.

Foreign policy can be a "gateway issue," meaning a candidate must pass a basic test of competence as far as supporters are concerned. But that’s about it. Campaigns thus treat difficult defense and foreign issues as potential landmines more than potential advantages.

"If you look historically at data going back to the post-New Deal era … the thing that runs elections, that drives outcomes, is rarely foreign policy," said Lynn Vavreck, a political science professor at the Universtiy of California at Los Angeles, at a conference on defense and foreign policy and elections late last year.

Thus campaigns don’t rush to discuss things they're not sure voters want to hear about. This year, there's been virtually no discussion of the changing role of nuclear weapons, Mr. Holt's question aside. Yet the US is on the verge of a historic rebuilding and restructuring of the current stockpile.

There's been little discussion of the overall effect of the long US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what that means for the overall Middle East. NATO issues have been raised only in the context of Trump's insistence that allies should pay more for the US defense they're getting.

Neither candidate has talked much about perhaps the most acute foreign policy question the winner will inevitably face: North Korea's drive to become a de facto nuclear weapons state, with missiles capable of reaching parts of the US. Both candidates, to varying degrees, say they'll get China to pressure Pyongyang. Spoiler alert: solving the problem is likely to take much more than that.

Commander-in-chief?

Overall, national security and foreign policy isn't playing nearly as big a role in the election as it should, says Jeffrey Engel, an historian and director of the Southern Methodist University Center for Presidential History. That's a problem, he says, because those are the areas where the choice of Oval Office occupant can have the most impact.

"The president is in charge of many things but his or her role as commander-in-chief and chief diplomat is perhaps where they have their greatest leverage and impact," says Dr. Engel.

Foreign policy should be a clear advantage for the Clinton campaign, says Engel. She's as prepared for that aspect of the job as any presidential candidate in decades. Polls show most voters agree with this assessment. In a late September Gallup survey, Clinton had a 26 percentage point lead over Trump on the question of which candidate is best prepared to handle foreign affairs.

The Trump reply to this is that Clinton in particular and the Obama administration in general was incompetent in this area and he will do better just by being Trump. Solutions are simple. It's a matter of implementation, in the Trump view.

In that sense much of his campaign is structured, not around foreign policy per se, but around his attitude of defiance to China, Mexico, and other foreign nations.

Most presidents have approached the world as a place which works better where nations work together as much as possible, says Engel. Trump's attitude is different.

"Donald Trump appears to view foreign policy as a zero-sum game, unlike any president in the 21st century," he says.

Clinton's problem may be that she knows solutions to world problems aren't simple, and that's not what voters want to hear. Rather than dumb stuff down, she avoids specific discussions altogether. So instead of a technical discussion as to what "first use" of nuclear weapons is, and why it is (or is not) important to maintain the strategic ambiguity that provides US officials against such adversaries as North Korea, Clinton pivots to a basic reminder that America needs friends.

"The American people thereby remain in darkness," concludes Professor Bacevich.